8 Black Designers Challenging the Status Quo With Socially Impactful Work

Places convey whether they are designed for us or not in often subtle ways. Cultural values lurk behind aesthetic choices, and small details signal inclusion or exclusion—both in the development process and the ultimate design. We spoke with eight Black designers whose work manifests social impact, both on a large scale—addressing deep-rooted sources of system injustice—and on a more intimate scale—creating interiors that cause a psychological shift.

Deanna Van Buren

Deanna Van Buren is cofounder of the Oakland, California–based Designing Justice + Designing Spaces (DJDS), a nonprofit architecture and real estate development firm established to work with incarcerated and formerly incarcerated communities to realize projects that embody the principle of restorative justice: holding people accountable for their actions and addressing the needs of survivors as a primary way of repairing the harm.

"I saw the public interest design movement had emerged," Van Buren says. "I was living overseas for a long time, came back to California, and saw groups like Public Architecture, Architecture for Humanity, and was like, ‘Oh, we can serve others besides rich developers and institutions!"

DJDS has branched out to address the larger implications of the criminal justice system, too, such as lack of economic opportunity, reentry into the community and recidivism, and closed-down jail infrastructure. But Van Buren emphasizes that at its core, the work is about producing good quality design.

"Of course, everybody’s personal experience plays into what they do," she says. "I would rather address the huge inequities of the patriarchy and white supremacy. I would hope everybody would be working towards that, but in my own personal experience, I have a bit more motivation to address that as a designer and an architect."

Emmanuel Pratt

Urban designer Emmanuel Pratt calls his work urban acupuncture or regenerative neighborhood development—pin prick-like interventions such as founding urban farms and repurposing foreclosed buildings as community spaces. His work eases tension and renews life in neighborhoods abandoned, unaddressed, or exploited by capital and government agencies. On the ground, it often means that he’s patching together broken systems, doing work that government agencies should be doing, and building out from there to expand the impact.

"There’s a moral sense of obligation and duty that you have to do it no matter what—because if you don’t do it, there’s more consequences," Pratt says. "Most of the work proves that something else is possible in the middle of all of this craziness. It’s not only possible, but it makes sense, and unless we illustrate it—make that image possible for people to imagine—there’s no vision."

Pratt’s Sweet Water Foundation transformed an abandoned house into a community school with a mural on the side. The lot, once vacant, is now a public garden. On another vacant lot, they created a workshop to teach carpentry and build furniture for public spaces from repurposed materials, developing a lesson plan to extend it as a model for schools and community organizations.

"The regenerative approach says there’s a framework for accountability, ethics, and morality," Pratt says. "There should be a seventh-generation principle, which is an ancient indigenous [principle]: How do I leave things better for the next generations? How do I shift the structures of consciousness to get people more aware of their responsibility on the planet? There’s a certain level of agency that gets to sustainability: it’s regeneration versus a degeneration."

Sheila Bridges

Renowned interior designer Sheila Bridges frequently appears in "best of" lists due to a long line of credits for well-known clients and public institutions that help amplify their narratives.

"I’ve been in the design industry for 30 years, and my job is, I’m a visual storyteller," Bridges says. "If I design for a client, I’m trying to help them tell their story, but in an aesthetic way that elevates the story that they might normally tell."

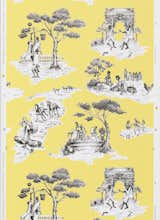

For her Harlem Toile de Jouy, though, the original client was herself. She wanted a wallpaper for her own house that spoke to her and resonated culturally. Referencing the jovial, pastoral scenes of toile patterns and influenced by Kara Walker with a subversive twist, she created a wallpaper and fabric that humorously subverts racial stereotypes. In it, a Black couple in 19th-century dress dance next to an ’80s boombox; a group of Black men play basketball with a wicker basket in a tree; a Black woman registers as a runaway slave, but is actually based on herself running her horses.

"The wallpaper really addressed a lot of things, but one of them was the idea of stereotypes and how stereotypes are meant to degrade us and generalize. There may be some truth that is then distorted," Bridges says. "I wanted to depict Black people in a celebratory and positive way," she says. "Self-examination is hard. This is my way of putting my own personal thoughts and feelings about race, about stereotypes, into the mix."

Francis Kéré

Internationally acclaimed, Berlin-based Burkinabe architect Francis Kéré has emerged as one of the most famous architects in Western Europe hailing from sub-Saharan Africa, winning high-profile commissions in recent years for the Serpentine Pavilion in the London and Venice Biennale. His designs meld modern and traditional idioms, developed through a communal approach and distinguished by a commitment to sustainable materials and construction methods.

"For me, this isn’t so much a bringing together of seeming opposites that can be clearly defined," Kéré says. "The forms I choose to create may have roots in my upbringing and the particular collage of experiences that is my own life, but a traditional form is simply one way to get inspired rather than something I consciously merge with something else. It’s much more fluid than that."

In projects like his 2016 Lycée Schorge Secondary School in his native Burkina Faso, the palette of red brick, concrete, eucalyptus, and brightly painted doors balances resonant curves, muted and bold colors, and hard edges. If some part of the design seems to reference the traditional courtyard of rural villages, it’s part of an impressionistic composition of vernacular and imported techniques—clay firing, modern construction, and industrial production—that responds to the givens of the design brief and program.

"As an architect, I need to understand the factual framework, which includes topography, available material, the room program and budget, for example, as well as the conceptual guidelines where you have the brief, the inspiration, the stakeholders, users, and of course also the less tangible aspects like imagination, the feeling the space should eventually achieve, and so on," he says.

With other international superstars like David Adjaye, his prominence has spread the visibility of the profession in places where Black architects remain proportionally underrepresented. "For sure I have noticed that the projects we have done in Gando have made it more common for people in Burkina Faso to aspire to be architects, as this is a much more visible choice of profession now."

Sara Zewde

A New Orleans native, landscape designer and urbanist Sara Zewde launched her office Studio Zewde in Harlem two years ago, having already won awards for her work in Rio de Janeiro that was rooted in her master’s thesis at the Harvard Graduate School of Design. While researching and theorizing a way of rethinking the nature of monuments, she found out about the discovery of a ruin of Rio’s transatlantic slave port buried beneath modern development. Rather than a wall of names, a statue on a pedestal, or an abstract form, Zewde proposed a memorial that would distribute the slave port’s memory in a constellation of everyday sites throughout Rio.

"The notion of the memorial, as we know it, is rooted in classical notions of monumentality, and we craft it around the idea of an event, or a discrete moment in time, or a hero, or a tragedy," Zewde says. "Slavery was not an event. Slavery was 400 years of the way that the world operated, and its effects are still present today. If you look at the way memory is constructed philosophically in Black cosmologies, time is not as linear as it’s perceived in Western time."

Zewde has since won prominent commissions in the U.S. like the redesign of Fairmount Park’s recreation areas in Philadelphia. She is writing a book about Frederick Law Olmstead’s travel through the slave states as a reporter for the New York Times before he developed Central Park, framing race as part of the origin story of landscape architecture. An urban design professor at Columbia University, Zewde argues that one doesn’t have to be a member of a group to design well for it.

"There is a responsibility on the part of architecture as a whole to say, ‘Why are we saying that, for some experiences, we’ll just never understand those or be able to design for those?’" Zewde says. "I challenge that. I challenge architecture to say, ‘No, what that speaks to is, we need to have more literature, more methods, more precedents that will actually allow designers to move beyond the cultural assumptions in the way we’re taught to design.’"

Roslyn Karamoko

Retail designer Roslyn Karamoko’s concept store Détroit is the New Black puts a marker down for Black hipster cosmopolitanism on Woodward Avenue, steps from the Shinola Hotel in downtown Detroit. A Seattle native and former fashion merchandiser and retail consultant for upscale department stores like Saks, Karamoko paid her dues in Washington, D.C., New York, and Singapore before launching her first pop-up store in 2015, using a Détroit is the New Black T-shirt to launch the concept. Interior-designed by Gensler and outfitted with locally manufactured displays, Détroit is the New Black curates a selection of stylish local talent along with national and international Black and minority design stars, among them Tracy Reese, Victor Glemaud, and Brother Vellies.

"It’s important to create a space and an expression of what underrepresented design looks like in a fully fleshed out retail environment," Karamoko says. "It started with that T-shirt as an expression of what does new Detroit look like, what does new inclusive and diverse Detroit look like. It’s definitely that play on words and a nod to gentrification, or the absence of Black people in the new developing economy in Detroit."

Yet in pockets of the city, it hums with a design-savvy, Black, cosmopolitan flair, with young artists attracted from around the country, and Karamoko’s store is a new hub. "There’s always been a Black creative class reaching all the way back to Motown, all the way up through J Dilla, and different street artists and sign artists coming out of Detroit. Currently, because Detroit has been more of focal point, that’s being magnified, which is exciting—it is a really cool creative energy happening here at the moment."

Justin Garrett Moore

Urban designer and executive director of New York City’s Public Design Commission Justin Garrett Moore reviews developments on city-owned property to improve quality of design and advocate for greater accessibility, diversity, and inclusion. During the Bill di Blasio administration, New York shifted from selling land outright to signing leases that allowed it more control and leverage over outcomes.

"Since we have jurisdiction, we’re able to be reasonable about making sure that if you’re advancing an initiative like affordable housing or good quality public space, that good design is a part of how you do that in a sustainable way," Moore says.

Moore also runs his own office, Urban Patch, applying principles of equity and sustainability to projects like an affordable, higher-density housing development in Kigali, Rwanda, that uses locally produced materials. In his role as an adjunct faculty in urban design at Columbia Graduate School of Architecture Planning and Preservation, he has run studios in smaller cities like Newburgh, New York, that suffer from vacancy and lack of revenue, applying a similar methodology.

"Our particular studio has always been talking about how to factor social and environmental concerns into conversations," he says. "A really important part of urban design practices is there isn’t one client. You’re working for a lot of different types of stakeholders and conditions, so you have to learn the social practice side of urban design: community engagement, understanding the political and social dynamics, keeping an eye on social equity, intergenerational considerations, etc. On the other hand, there’s this idea of having a greater understanding of things like impact on environment, on a global and regional scale, that encourages more systems-impact orientation than what you would find in a traditional urban design. We jokingly call it ‘big architecture.’"

After the 2015 Black in Design conference at Harvard GSD, Moore came together with a group of attendees to form BlackSpace, a collective of interdisciplinary designers working to improve the way that community development happens in neighborhoods. Their manifesto includes more dialogue and inclusion, the creation of deeper relationships, the practice of listening deeply and accepting criticism, and catalyzing Black joy as part of the process.

"Very often, there are best practices for how you do community development work," Moore says. "But when you apply those business-as-usual practices in communities that either have not had a strong track record of having successful projects, or have distrust of government or private sectors, the tools and approaches may not work."

BlackSpace has partnered with Made in Brownsville to document, preserve, and amplify the east Brooklyn neighborhood’s Black culture, and has initiated a 14-week, local history scavenger hunt in Bed-Stuy with the nonprofit Children of Promise.

Antionette Carroll

Antionette Carroll founded the Creative Reaction Lab in St. Louis in the aftermath of the Ferguson, Missouri, protests against the killing of Michael Brown, Jr. by a police officer in 2014. She launched a 24-hour design challenge that produced five graphic design, public art, and educational campaigns focused on racial inequality and police brutality. Since then, Creative Reaction Lab has pioneered a creative problem-solving method Carroll calls equity-centered community design.

"We see our work intersecting the space of education and civic engagement," Carroll says. "It’s not enough to raise people’s consciousnesses; we need to move them to action and give them the tools and capacity to do so." Equity-centered community design is concerned with how racism functions in relation to issues like housing, healthy food access, and mass incarceration.

"Our work is around building the capacity of community members, who we deem living experts, to be able to address these challenges from within their own communities," Carroll says. "We are working to build a new kind of leader that we call ‘redesigners for justice’: these individuals who will challenge inequities in education, government, media, and health, understanding that many of the ‘-isms’ that we are dealing with have been by design, and that means that they can also be redesigned."

Related Reading:

Urban Planner and MacArthur "Genius" Emmanuel Pratt’s Vision for Chicago Is Radically Simple

Get the Pro Newsletter

What’s new in the design world? Stay up to date with our essential dispatches for design professionals.