Urban Planner and MacArthur “Genius” Emmanuel Pratt’s Vision for Chicago Is Radically Simple

Those paying attention to this year’s Chicago Architecture Biennial may have gotten a glimpse of the kind of work that Emmanuel Pratt does.

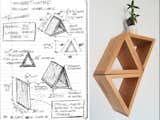

The artist, designer, and urban planner constructed a house-like pavilion based on the worker cottage—a single-family vernacular repeated across Chicago in the 19th century—and set it on tracks in an abandoned lot on the South Side of Chicago. The average person could push the timber structure back and forth. Then, in a span of six hours, he took apart the 10,000 pounds of lumber and put them back together inside the Chicago Cultural Center.

"It was a great opportunity to talk about what’s the appropriate size of a footprint of a house," says Pratt. "’Cause the South Side is all zoned for single-family residential. But there are a lot of empty lots here, since a lot of the houses burned down."

In conversation, he rails against big developers’ laissez-faire approach to neighborhood development—a problem he looks at through the lens of architecture and urban planning: investors stand from afar, motivated by for-profit models that disenfranchise poorer neighborhoods and push out residents for new waves of gentrification.

Ten years ago, Pratt hatched Sweet Water Foundation to flip the script. With a small team, Pratt has transformed several adjacent parcels of empty land into lively neighborhood magnets: a garden, a center for performing arts, a meeting house for community conversation, and an apprenticeship program, to name some. It’s a model for neighborhood enrichment that marries two familiar adages: "Teach a man to fish," and "Build it, and they will come."

Last month, Pratt was one of 26 artists and visionaries to receive a 2019 MacArthur Foundation fellowship, colloquially called the "genius" grant. We spoke with Pratt to learn more about his take on regenerative design, what he means by urban acupuncture, and fractals as a metaphor for the expansion of healthy communities.

So first, a broader question: what are the things that set you down the path toward the work Sweet Water Foundation is doing?

Pratt: I grew up in settings where I was constantly on the verge—the verge of erasure, the verge of loss. So it was rough. I grew up an artist and a musician, and drifted into architecture because people said I should get a real job. But I found architecture as an outlet that let me creatively explore.

But then I was frustrated by silos and reductive responses to real-life challenges in architecture. [The field] is disproportionate as to where funds are expended or how certain types of designs are allocated to certain kinds of communities. So neighborhoods like where I grew up were devoid of those design opportunities.

But it’s weird, because poorer neighborhoods have the space; they have the most need for true architectural design interventions and planning interventions, but because there aren’t capital means, those are the places that remain neglected.

So I left architecture because of its reductive approach to neighborhood design strategies. You can’t just invest in a built structure; there’s a context that needs to be looked at. When I went into urban design, that’s what I started to look at: the bigger context.

"When I went into urban design, that’s what I started to look at: the bigger context."

—Emmanuel Pratt

How are you approaching urban design? What makes it different than just looking at a single building or development?

Once I founded Sweet Water as a solution-oriented approach to urban design—as inspired by the greats like Jimmy Boggs in Detroit—I started saying, "Oh, there’s more of an urban acupuncture type of response": identify a stress point, figure out the contextual history behind it, do an installation that is an inserting design moment, something that offers something to the community to respond back.

Then, create space for biofeedback to design what a space should be, appropriately. That’s how I linked education to career paths that lead to gardening, farming, and carpentry for people. Because when you do that, they experience from learning.

Was this the goal for Sweet Water from the beginning?

When we started Sweet Water, we were in classrooms asking "How do we connect disconnected learners?" They were in neighborhoods that were historically redlined, or didn’t have the right support or infrastructure or the means.

So we started doing hydroponics and aquaponics in the classroom kind of as living labs, and there was an instant "aha" moment. We evolved STEM into STEAM by adding the "A," which stood for agriculture, architecture, and aquaponics.

Boom! Once that caught on and resonated, then parents, uncles, aunts—all kinds of people were excited to get in the mix. But when they started to shut the same schools down and close—are you familiar with the schools shutting down in Chicago?

I am not, no.

They closed 54 schools down at the same time. At the same time. If you look at the confluence of the maps, it’s in the same neighborhoods on the South and West Sides that have historically been redlined, and have been historically lacking all kinds of support.

So while you were building up programs via Sweet Water, these schools and their neighborhoods were being cut down?

It’s affected our organization and my team because we’ve been building all these relationships with human infrastructure and human capital only to have that loss again. It just so happened that after working with the aquaponics center at Chicago State in 2011, we started Sweet Water in 2009 doing school-based projects. But then we took those projects and found a 10,000-square-foot warehouse and turned that into an aquaponics center.

Then that naturally turned into an indoor/outdoor relationship with new projects surrounding gardening and farming year round. That became a great way to talk about design—true design, contextually, per neighborhood, and per resource.

At the R-N-D Park—a reclaimed five-parcel piece of land—a shou sugi ban structure was built by the community to explore new forms of housing development. The name "R-N-D" doubles down: the park is a place for research and development, and it’s an acronym for Sweet Water’s regenerative neighborhood development strategy.

So that was a kind of turning point, it sounds like.

Basically by the time I got asked in 2014 to take on a neighborhood park in Washington Park and Inglewood, we had a library of ideas to translate urban acupuncture from a theoretical framework into a practice.

And this is the big culmination: once we got the Perry Ave Commons—the Perry Ave Farm, an active community farm—we got the house across the street and turned it into a community school. Then we worked with Chicago public schools with a program in order to build out these gardens for the residents to bring in their families.

So now we had a farm, a garden, and a community school, all in a formally foreclosed house. It just so happens that the farm we started was one of the worst schools in the history of Chicago.

This is the Moseley School you’re referring to?

Yeah, the Moseley School for social reform for orphans and incorrigibles.

Once we developed a program there, we got a significant boost from ArtPlace America. That’s when I really started to hone in.

Before that, I got a LOEB Fellowship, which allowed me the time and space to work with other people and really think through the idea for a regenerative neighborhood strategy. Then we pitched that as a grant to ArtPlace, and then that’s when I got a chance to design the barn.

Then we raised the first timber-frame barn in Chicago since the fire in 1871. It became a gathering space for up to 200 people, and it began to activate the farm in a very public way—we had dances, performances, classes, workshops—it’s a very public thing. And, it was a great way to have a centralized space that would draw people from the public but also draw people from everywhere in the world.

So now [Sweet Water] is on Google Maps as a tourist attraction. It’s a five-star business.

That’s amazing. So you have a presence way beyond the local community.

We had people from Ireland, London, Japan—everywhere in the world—wanting to pitch in at Perry Ave Farm and the Reconstruction House across the street. And the best part is that they were here working side by side with our team, locally.

So then all of a sudden fellows from Harvard, University of Chicago, and University of Michigan come, to name a few, and we have something that feels completely global. People don’t believe it until they come here and see it. The best way to do something in common is to be in a similar platform and build something, grow something, share the food, do the work together, and celebrate.

Sweet Water has a few different parcels you've developed—the Reconstruction House, the Thought Barn, Perry Ave Commons, the R-N-D Park. What ties them all together?

We do really flexible, modular installations that allow for these really nice spaces for biofeedback. When I say biofeedback, I mean that humans can insert thought and do real, nice collective design work. And inevitably this has an impact on our ecosystem. So it’s surrounded by flowers, we put a garden in, we have a farm across the street, ya know, it’s an ecological evolution of the space.

Now we have a regenerative neighborhood development strategy. The result is that now we have a regenerative design team that is launching next year.

Congratulations—how big is that team?

We have a core group of eight right now. It’s a great framework for folks that are already part of our ecosystem. We have these residents that work side by side, and they might drift off and go somewhere else for a period of time. One of the graduates from our fellowship from two years ago, she’s now a practicing architect in New York. But she checks in all the time.

But this is not university driven at all, this is all a living, real world laboratory-campus. We call it a campus—the commons is a campus for Sweet Water for people to do work and research. But we do interface with a ton of universities.

So you’ve said you have kind of a model in place now, and you have a team of people, so is the idea to then replicate?

Do you know what a fractal is? Fractals are scalable geometric shapes that scale up and out over time and become recognizable patterns.

We’ve designed every lesson plan we have, like outdoor public space for performances, or floors, or even the barn, or the meeting house, to be scalable. Everything we do—the garden beds, the green house—everything we do is a lesson plan that we can scale.

We are surrounded by five or seven neighborhoods. So by default people show up from these various neighborhoods. And by default, somebody knows someone who says, "Hey, I wanna do gardening, or I want to build something, or I love food. So I’m gonna come to you instead of going to that expensive grocery store."

People need fresh good food, period. Full stop. What’s the point of growing organic lettuce if you’re selling it at a premium? That’s just immoral, unethical.

You’re creating this kind of magnet.

Absolutely. That’s a more appropriate term. We live in a time of polarization. Where people are alienated or ousted, or they’re gentrified and displaced, and we’re reversing that. We have to do something that becomes almost like a magnet for people to come together to find each other in order to reclaim their humanity. That’s what the work is about.

Let’s move away from traditional, 20th-century design practices that have created voids in our cities, alienated populations, and closed down the schools. We’re in crisis mode. But now we have a tremendous opportunity to look at a new beginning. And that’s where the regenerative design and development is. That’s why we do the work.

And then, realistically, the master plan is dead. The concept in the 20th century of trying to control from a very mechanistic type of micro-managerial way doesn’t work. We have to have another way of evolving cities that does involve a plan—I’m not saying it should be chaos. Give space for a little bit of life, a little space in between to develop what people planted.

"We have to do something that becomes almost like a magnet for people to come together to find each other in order to reclaim their humanity."

—Emmanuel Pratt

Emmanuel Pratt first erected this timber structure on a vacant lot in Chicago’s South side. The form riffs off the worker cottage, a single-family vernacular popularized in the 19th century. In the span of six hours, he tore it down and rebuilt it here, inside the Chicago Cultural Center, as an exhibit for the architecture biennial. It’s meant to start conversations surrounding affordable housing in redlined neighborhoods.

And that goes back to the idea of biofeedback, so development isn’t just a one-way avenue of thought.

Yeah, totally. Our neighborhood is four contiguous city blocks with a plan to go 10 blocks. It’s not crazy. We went one block a year for every year we’ve been here. It’s very real. But we have to keep developing with the right partners, so we can do maybe 10 houses a block. That’s not a lot because really there’s a lot more capacity for housing that could go up.

We have space across the street that’s been zoned for manufacturing that hasn’t been manufacturing since 1970. So why is it still zoned for lightweight manufacturing? Maybe cottage industry needs to come back at this scale. Maybe the local production of housing needs to happen right there. Maybe indoor farming needs to happen right there. So let’s do it. We’re gonna try to set up some kind of small scale manufacturing space for that to happen.

Where most might steer clear, I’m impressed by your ability to see opportunity.

I’m glad you brought that up because you’re right, but not in the traditional opportunity zone approach. When you develop cities with a single-minded return on development, then you’re chasing capital. That’s all that matters, right?—how much money you get. Period. So of course, if you actually look at the historical practices of institutional segregation or racism that date back to 1936, this leads to redlining. This is how cities developed from 1936 onwards.

I incentivize development in areas that have not been developed in a long time. So realistically these opportunity zones are the redline neighborhoods—they’re the ones that suffer. So if you do that as business as usual, and you do that without some level of sensitivity for biofeedback, it’s gonna become a far worse hole or chasm. It’s gonna be a rift for society where you’re gonna accelerate displacement, polarization, and alienation.

It just so happens that our site is an opportunity zone. Go figure! So now we’re in conversation with people saying, "Why don’t you look at this as a different approach to actually invest in a social enterprise?"

With Sweet Water, we’ve created something with global presence and local roots. We’re actually building up this area in the South Side of Chicago in a different way, a much more right way. I’m not gonna say it’s the right way, but it’s a better way. It’s a far better ecological and humane way of development that could become an example of how we develop a pipeline for thought. Right?

Learn more about Sweet Water Foundation.

Published

Get the Pro Newsletter

What’s new in the design world? Stay up to date with our essential dispatches for design professionals.