Urban Usonian

In the early part of the 20th century, Frank Lloyd Wright advised his clients to go "just ten times as far as you think you ought to go" from the city. In the early part of the 21st century, the suburban dream is far from over, but our cities are no longer viewed as harbingers of ills. From Omaha to Oakland, once-neglected urban spaces are seeing an unprecedented revitalization as a new generation eschews the monotony of the commuter communities for the vibrancy of city life.

With this decision, a person usually faces the limitations of the already-built environment or myriad rental situations. Kent Dayton, however, had an altogether different opportunity: a gut renovation. The Boston-based photographer acquired a partially built-out 1,500-square-foot loft, carved from the seller’s 4,000-square-foot space, with the intention of consolidating his life and work. When he approached Michael Grant, principal of Grant Studio, with his program, the architect was immediately reminded of Frank Lloyd Wright.

While Wright is known for his capacious estates, he was also an advocate of affordable architecture through his Usonian houses. While these low-cost single-family homes were, true to Wright’s ideals, located outside of cities, given Dayton’s spatial and practical constraints, Grant wondered what an urban Usonian might be like.

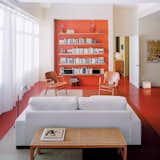

With plumbing fixtures, concrete floors, and ceilings firmly in place, Grant devised a plan that, through the clever use of transformable elements and mass-produced materials, fulfilled both Dayton’s needs and Grant’s notion of an urban Usonian. The L-shaped apartment opens onto a digital imaging studio. As one progresses past the kitchen and then the living room, the ceiling rises twice, giving a sense of spatial expansion and providing a location for Wright-inspired cove lighting.

A second bedroom, equipped with a folding bed and pullout bedside tables, doubles as a photo studio. Two large walnut-veneered, steel-framed panels slide on recessed ceiling tracks, enabling Dayton to separate his living and working areas. "Unlike some photographers, I don’t especially like looking at my equipment," he quips. In a final Wrightian touch, the concrete floor is covered in a deep Cherokee-red epoxy, which not only looks smart but absorbs and radiates thermal energy.

Completed for a mere $73 per square foot, Grant’s design lives up to its Usonian ideals; however, the raw spaces in which to build are a certifiable rarity (especially in heavily zoned Boston). Grant nonetheless sees the opportunity "for a new type of building to accommodate a new type of home, and a process of making one’s home in the city."

Published

Last Updated

Get the Dwell Newsletter

Be the first to see our latest home tours, design news, and more.