Simply Sustainable

Located in a hidden valley on the picturesque Izu Peninsula, a few hours west of Tokyo, the Watanabe Residence, designed by architect Tadashi Murai, looks more like an imposing black box propped amidst the wooded landscape than a model of environmental friendliness. But homeowner Hiroyuki Watanabe’s unusual background helps explain his choice of shelter, and certainly his lifestyle. One of a growing group of Tokyo refugees, Watanabe recently traded in his three-piece suits for overalls and moved to the mountains, finding more meaning turning wood than churning out spreadsheets. Peering inside his home, one finds a similar disdain for tradition and a fondness for nature, all encompassed in Murai’s ingenious building system composed of modules pieced together to form a customizable green home.

The genesis of Murai’s prototype, known as the Aero House, occurred in 1999, as the result of a commission to provide a reception area and office at a woodland cemetery. The remote location meant that the usual utilities and services—electricity, gas, water, sewage—were not available, and the project brief indicated that the building should be easily transportable. Far from being deterred by these unusual constraints, Murai instead saw an opportunity to conduct an experiment in sustainable architecture, and produced a small, mobile box for the client. While it mainly functions as an office, this prototype unit was designed to have the capacity to support periods of habitation.

The cemetery project was the first iteration of what would eventually become Hiroyuki Watanabe’s home. The Tokyo transplant commissioned a fully equipped structure that comes with its own power, heating and cooling, water, and waste-disposal systems, all designed to minimize environmental impact and maximize self-sufficiency. While a laundry list of sustainable features were available, Watanabe opted for only some of them.

In a fully loaded Aero House, low-voltage electricity is supplied by a system of wind generators, solar cells, and storage batteries. Heating and cooling are handled by passive-design techniques: In the winter, sunlight is allowed to penetrate to the interior, and air heated by a solar wall is circulated to the living space; in the summer, cool air from the underfloor space is pumped inside. A green roof planted with moss forms a natural insulation barrier that further reduces energy demands. The water system consists of a freshwater storage tank and graywater recycling for irrigating the green roof. A composting toilet completes the package.

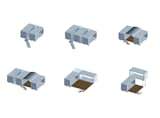

The modularity of Murai’s design reduces construction waste and keeps building costs low. The basic module is a roughly 20-by-8-foot wooden box that’s ten feet high and open on two of its long sides. These units can be configured in linear, stacked, or scattered combinations to create a variety of dwelling types (shown at right and on previous page). A single module is easily set up in just one day by a crew of four to six workers while an entire house takes longer, depending on a range of variables like the number of modules used, the site, ground conditions, and so on.

The standard timber materials of the Aero House, combined with the modular approach, allow users to add and subtract at will. And if the owner moves, the entire building can easily be transported to the new site, bypassing the wasteful "scrap-and-build" mentality that is common in Japan.

"I aim for a kind of ‘non-design’ design," says Murai of his flexible prototype. "I don’t think it is desirable to control every element and detail—a beautiful, clean box should be sufficient. The rest can be left to the users’ needs and creativity."

Published

Last Updated

Topics

Green HomesGet the Dwell Newsletter

Be the first to see our latest home tours, design news, and more.