Mid-City Modern

Atlanta is known for many things—Coca-Cola, cotton mills, and Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., to name a few—but modern architecture has surely never been one of them.

In fact, mention of the city usually calls to mind the sprawling suburban developments that ring the metropolis and threaten to turn all of rural Georgia into one massive cul-de-sac. Contrasting with the legacy of sprawl is something of an architectural renaissance percolating in Atlanta’s older neighborhoods within the last few years: a host of urban infill projects and loft conversions that are slowly altering the suburban-wasteland image.

A recent and none-too-bashful addition to the city’s modern pantheon is Shawn Moseley’s dramatic new home in the McDonough/Guice neighborhood.

Moseley, a 34-year-old longtime Atlanta resident, hadn’t considered building a house when he started looking to buy his first home. Tired of renting but disdainful of most flimsy new construction, Moseley figured he could find an unrenovated loft or an older house to serve as a blank canvas for his ideas. But instead of an anonymous loft in a converted warehouse, he is now the proud owner of the kind of house that inspires Sunday-morning drivers to stop in the middle of the street, car idling, as they take in the slightly alien silver box.

Seven years in a rented bungalow followed by a year in a flood-prone loft had convinced the young music-industry executive, amateur furniture designer, and former architecture student that he would be happiest buying a solidly built industrial space he could redesign himself.

His realtor took him to see downtown and midtown lofts, which were disappointing. "I quickly realized how limited my options were," says Moseley. "Every place I looked at was going to require an $80,000 renovation just to be habitable. What was available was just way overpriced, and didn’t exactly fit my needs."

After months of searching for a suitable space, Moseley was lamenting his fruitless hunt over a Saturday-afternoon beer with his realtor—and old friend—David Prasse, who had bought a converted turn-of-the-century trolley station in a quiet neighborhood southeast of downtown Atlanta. As the afternoon wore on, Moseley suddenly remembered having gone with Prasse on a walk-through of a house in nearby McDonough/Guice the previous year, a house that now stands next to Moseley’s. The designer of that house was also responsible for Prasse’s trolley station conversion, and Moseley wondered aloud if he was still looking to develop the lots adjacent to the house they’d seen. "Dave picked up the phone, made a call, and we drove over within 15 minutes to look at the lot," recalls Moseley.

The designer was M. Scott Ball, who has a local practice and is co-executive director of Atlanta’s Community Housing Resource Center. Ball was hoping to develop a group of houses on land he owned in the racially and socioeconomically mixed neighborhood to use as showcases for intelligently built, moderately priced housing.

While Moseley was looking for a particular kind of modern aesthetic that was also within his price range, Ball was more interested in practical issues. "The CHRC’s largest program is a housing repair and rehab program for low-income homeowners," explains Ball. "In the nearly subtropical climate of Atlanta, there are many environmental forces hostile to the stick-built, Sheetrocked, carpeted boxes in which we have grown accustomed to living." Southern heat and humidity simply don’t work well with hollow-walled cavities, which trap moisture and wreak havoc on Sheetrock and wood framing. The same kind of homes that work quite well in California or Michigan become maintenance nightmares in the sticky Georgia heat, especially for older residents.

The CHRC hoped to use their experience to research, design, and build a home that would challenge community expectations of housing design and suitable materials and serve as a laboratory for Ball’s sustainable design ideas, yet still maintain a connection to the architectural traditions of the region.

"What would a house look like," Ball says he hoped to discover, "if we eliminated wall cavities, Sheetrock ceilings, interior bearing walls, and other items that typically create problems as a house grows old and the use patterns change?" The overarching goal was a design that worked better and was more grounded in Atlanta’s particular set of needs than a "traditionally" built home. The freedom for designer and client to let their imaginations run wild and build something interesting and unique was icing on the cake.

With Moseley and Ball’s joint efforts (with assistance from architecture students at Southern Polytechnic State University, where Moseley studied design in the late ’80s), the house was finished in less than a year and emerged as exactly the type of urban space Moseley had envisioned, but situated on a quiet residential street ten minutes from downtown Atlanta. The 2,000-square-foot structure (plus an 1,100-square-foot basement workshop and garage) is essentially a freestanding loft, defined chiefly by its gull-wing roof, clerestory windows and the home’s most dramatic feature, a front wall that swings open onto an exterior terrace.

Eschewing the stick framing that CHRC inspectors have seen cause such trouble for many homeowners in Georgia’s year-round humidity, the walls were erected from structurally insulated panels (SIPs) built off-site, delivered, and raised into place. The exterior of the house is clad in a mixture of corrugated and flat sheet metal. It requires little to no maintenance as the house ages and is an overt nod to vernacular metal-roofed architecturecommon to the region—from corrugated farm buildings to industrial warehouses to the standing-seam metal-roofed bungalows that dot inner Atlanta. Likewise, the house’s dramatic eaves are reminiscent of the deep awnings and large front porches that have long been the perennial design solutions for escaping oppressive Southern summer heat.

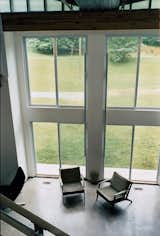

"One of the most important things about the design was fitting the house to the site," recalls Moseley when discussing how the structure took shape. "When you move from conception to final design, you start to realize what kind of impact things like budget, building codes, timeline, and especially the site have on a project." Preliminary sketches showed one-story buildings with flat roofs, but upon continual examination of the site, the designers realized that a horizontally oriented structure was not right for the location. The final vertical, concave design relates to the topography in a way that restrains and tempers what is otherwise an undeniably bold structure. A tree- and kudzu-filled valley just beyond the house is echoed by the butterfly-shaped roof. And the height of the building actually complements the sloping site more gracefully and unobtrusively than the original low-slung designs would have. Inside, clean lines give the light-filled space a sense of dignified composure without seeming stark or cold.

Minimal trim and finish work, use of salvaged or off-the-rack materials, and a lot of work by Moseley and Ball on nights and weekends served to keep costs low and to create the simple beauty and drama the designers were hoping to achieve. These decisions also reflected Ball’s original intent to show that smart, livable design need not necessarily be unattainable. With construction costs of just over $110,000, the house was built for only $32 per square foot.

The open-plan layout flows unencumbered from room to room and level to level, allowing Moseley to live in the entire house as if it were one large living room, a system that fits his hectic and nocturnal lifestyle quite nicely.

Several design elements emerged as construction progressed, most notably a custom staircase that seems to float above the concrete floor and a 40-foot-long kitchen counter that Moseley jokes would make a great Internet café if he’s ever strapped for cash. The staircase was designed after owner and designer fell in love with the four-by-ten wood joists they had ordered to support the second floor, and the counter was inspired by (and built from) glulam beams that arrived to form a load-bearing wall that would span the patio doors.

Although the house is unapologetically modern, and starkly so, it has elicited interest and excitement from local homeowners. "Other than a couple little kids who rode up on bikes and hoped we were building a nightclub, we’ve had zero issues with unhappy neighbors," notes Moseley with a grin. "I think most people are just happy to see something new and interesting in the neighborhood."

Published

Last Updated

Get the Dwell Newsletter

Be the first to see our latest home tours, design news, and more.