7 Supervillain Lairs Set in Deviously Well-Designed Homes

It’s hard to find a Bond villain who doesn’t live in a bold, imposing dwelling. They tend to plot their world takeovers from lavish modernist hideaways—and these shadowy spaces are finally getting their moment in the sun. Lair: Radical Homes and Hideouts of Movie Villains, a 2019 book by Chad Oppenhiem and Andrea Gollin, showcases the homes of Hollywood’s most nefarious and wicked movie villains.

The heavy, black-and-silver book includes 15 legendary hideouts, an essay on modernism and morality, discussions with production designers and directors, and an interview excerpt with renowned architect John Lautner. From Lex Luther’s palace under Grand Central Terminal, to Blofeld’s volcano, world domination never looked so good.

Blofeld’s Volcano—You Only Live Twice

Arguably the most wildly original setting in the glorious pantheon of celluloid villains’ lairs, Blofeld’s jaw-dropping hideout deep in the hollowed-out core of an extinct Japanese volcano was instantly iconic. Its allure is such that it later became a loving target of Mike Myers’ 1997 spy film parody, Austin Powers: International Man of Mystery, as well as the model for Syndrome’s lair in 2004’s The Incredibles. Possibly the crowning achievement of legendary Bond production designer Ken Adam, Blofeld’s volcano refuge is completely undetectable thanks to a hydraulic retractable roof made to look like the surface of a lake in the volcano’s crater. From this camouflaged setting, which just happens to double as a subterranean rocket launching pad, Blofeld plots his brand of global chaos. A 148-foot-tall hangar-like open space with floating staircases, helipads, and its own shiny steel monorail system (not to mention an army of henchmen in color-coded jumpsuits), Blofeld’s Japanese base of operations could only belong to a true sociopath. Why? Because it also features a large, kidney-shaped indoor pond full of razor-toothed piranhas used to mete out punishment to his minions who have come up short.

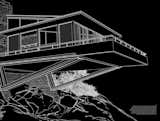

Garcia House—Lethal Weapon 2

Villain Arjen Rudd’s modern, canyon-top lair was an integral part of the Lethal Weapon 2 screenplay from the very beginning. Its role only grew larger as the more downbeat first draft of Shane Black’s script (Gibson’s Riggs was originally fated to die at the end) was revised by Black’s successor, Jeffrey Boam. The challenge was finding an existing Los Angeles–area structure that matched the one imagined on the page. John Lautner, the American midcentury-modern master who apprenticed under Frank Lloyd Wright in the 1930s, designed Garcia House in 1962 for jazz arranger Russell Garcia. It still sits high atop the Hollywood Hills at 7436 Mulholland Drive. With its unique almond eye shape topped by a curved, parabolic roof and supported by steel stilts sixty feet above the canyon below, the house is also known as the Rainbow House, after the colorful stained-glass panels that dot its facade.

The Vandamm House—North by Northwest

Ostensibly built into the side of Mount Rushmore, it’s hard to imagine a cooler, more creative villain’s lair than the jewel-box modernist home in which Phillip Vandamm plots and schemes in North by Northwest. Why there? One reason may be that Hitchcock and screenwriter Ernest Lehman had already settled on using the presidential peak as alocation for the movie’s climax (one of the original titles for the script was said to be "The Man inLincoln’s Nose") before figuring out quite why the characters would assemble there. So that’s whereVandamm’s hideout was established.

In reality, though, this jaw-dropping home is simply an example of old-fashioned Hollywood movie magic. For obvious reasons, there is no such house on Mount Rushmore. In fact, there is no such house, period. The stunning,sleek horizontal lines of Vandamm’s getaway were inspired by and modeled after Frank Lloyd Wright’s work, and Fallingwater in Pennsylvania was particularly influential. This impossibly sophisticated lair seems hewn right out of the face of the mountain—a seamless extension of its natural surroundings. With its limestone exterior and timber accents, not to mention its expansive glass windows, the swank structure is supported by a concrete cantilever and steelbeams. It looks like the high-altitude nest of a very wealthy bird of prey.

An Alaskan Compound—Ex Machina

Mad tech mogul Nathan Bateman’s home has gorgeous, expansive views of a lake and mountains, but an underabundance of trees, considering the film’s Alaskan setting. Tall trees were imported and placed on 20 meter-high stilts to create an Alaskan vibe. The hotel, perched on a steep levee within a nature reserve, is a minimalist marvel that blends into the wilderness—in building the hotel, no alterations to the terrain or rock blasting were permitted.

Elrod House—Diamonds Are Forever

A filthy-rich supervillain like Stavro Blofeld has no shortage of scenic locations where he can hide out and plot the next step in his devious will-to power plan for world domination. But even so, the desert spread where he temporarily sets up camp in Diamonds Are Forever is an indelibly cool one—a modern architectural marvel that’s not just set in the rocky desert but that is one with it.

Designed by American architect and Frank Lloyd Wright protégé John Lautner, the Elrod House was built in 1968 for interior designer Arthur Elrod. Located at 2175 Southridge Drive in Palm Springs, California, the house is set on a craggy ridge that affords it panoramic views of the San Jacinto Mountains. However, the words "set on a ridge" don’t do its setting—or design—justice. The ridge is actually incorporated into the home, with giant boulders kept in their original place and acting as walls and room dividers within the house, bringing nature inside.

Grand Central Terminal—Superman

Between the lavish renderings of the planet Krypton and Superman’s Fortress of Solitude, the Superman filmmakers would be forgiven for cheaping out when it came time to dream up Lex Luthor’s lair. Instead, they came up with one of the most creative sets in the entire film. Luthor’s hideout is two hundred feet below the streets of Metropolis (in the film, clearly New York City) in a condemned, abandoned concourse of Grand Central Terminal. Luthor has turned this forgotten Beaux-Arts gem, with its cream-colored Botticino marble staircases and Tennessee marble floors, into a palace fit for a Roman emperor. There are arched walls lined with books, palm trees, ornate parlors filled with oriental rugs and antiques, and a marble staircase that was formerly a track entrance, the lower level of which is now submerged in water and has been transformed by Luthor into an opulent swimming pool. It’s like his own version of Hugh Hefner’s grotto. There, he can swim laps in a lime-green bathing suit (and matching bathing cap), relaxing as he fine-tunes his evil master plan.

Wallace Corporation Headquarters—Blade Runner

Niander Wallace’s brutalistic Wallace Corporation Earth Headquarters towers over 2049 Los Angeles, a gloomy dystopia—an apocalyptic, haunted, yet oddly beautiful landscape lashed with dirty rain and hologram porn dolls, radioactive smog and neon-tinted favelas. Glowing billboards from Atari and Pan Am loom over the city’s grimy underbelly. (In this alternate reality, both companies are global giants.) DNA sequences are printed on microfilm and iPhones don’t exist. It’s even more joyless than the Los Angeles of the original Blade Runner, which is saying something. The scale of Wallace’s dark and foreboding lair puts every skyscraper around it to shame with its trio of slanted towers framed by squat, pyramid-like buildings (a visual nod to the Tyrell Corporation’s ziggurat in the original Blade Runner). Production designer Dennis Gassner used the word "brutality" as a touchstone in developing the film’s aesthetic; that was director Denis Villeneuve’s guidance when Gassner asked for a one-word directive. As he told Vanity Fair, "I developed a pattern language we used to create the rest of the city…the tower, police station, and other elements reflecting a more brutal universe—things that were robust enough to fight against the elements and remain standing, like pyramids." Filming took place in part in Budapest, among the city’s massive, brutalist architecture, which perfectly served the film’s visual mood.

Buy the book

Published

Last Updated

Get the Dwell Newsletter

Be the first to see our latest home tours, design news, and more.