The Frankfurt Kitchen Changed How We Think About Housework

Welcome to Origin Story, a series that chronicles the lesser-known histories of designs that have shaped how we live.

If the kitchen is really the heart of the home, it better meet the demands of the era and the needs of those who use it. A post–World War I affordable housing program in Frankfurt, Germany, led to the development of what’s considered the world’s first mass-produced fitted (built-in) kitchen, devised by Austrian architect Margarete Schütte-Lihotzky (one of the country’s first female architects). The basic goal of the Frankfurt Kitchen was to make housework more hygienic and less time-consuming for working women, who then as now bore the brunt of the burden of domestic labor. Its compact, standardized design provided a model for kitchens throughout the 20th century, and its guiding principles laid the groundwork for many of the cost- and space-efficient features of today’s cooking spaces. Here’s how it came to fruition.

User-Centric Design

The New Frankfurt housing project, led by architect and city planner Ernst May, had three main goals: Increase postwar housing supply, improve quality of life for working families, and accomplish both of those points efficiently and economically. In 1926, May tasked Schütte-Lihotzky with designing a space-efficient kitchen for the project’s modest apartments. To do so, Schütte-Lihotzky conducted detailed studies and interviews with housewives and women’s groups about what worked and what didn’t work in their existing kitchens.

Factory Precision

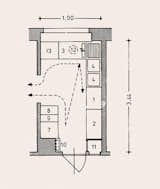

Schütte-Lihotzky drew inspiration from the theory of "scientific management"—popular in the United States at the time for optimizing workforce efficiency in factories—seeing the kitchen as a self-contained factory. The architect drew from the efficient and easily replicable design of railway dining car kitchens, with every detail of the Frankfurt Kitchen’s 6.2-by-11.3-foot layout aimed at reducing the time needed to move between tasks. There was built-in wooden storage (painted blue in a prototype, as scientists at the time reported the color repelled flies) and easy-to-clean surfaces like beech and linoleum, as well as an ergonomic workspace where the most-used items were within arm’s reach. A sliding door closed off the space from the rest of the apartment. To lower the cost, the Frankfurt Kitchen was designed to be prefabricated and mass-produced in small batches (with occasional variations).

A Domestic Laboratory

Schütte-Lihotzky outfitted the Frankfurt Kitchen with a variety of gadgets. The cook box was something like an early iteration of the Crock-Pot, except that it was an insulated container that allowed food to finish cooking using its own heat from boiling, minimizing energy costs. Labeled aluminum storage bins for ingredients—with spouts for pouring—fit neatly into identical wall cubbies. A fold-down ironing board could be tucked away, the ceiling light was adjustable, and a removable garbage drawer streamlined waste disposal.

The Kitchens of Tomorrow

Some 10,o00 Frankfurt Kitchens were installed in the city’s new public housing units from 1926 to 1930, but their adoption wasn’t without challenges. Many residents struggled to adapt to the design, prompting the city to produce instructional—and promotional—materials, including silent films and pamphlets. Though the rise of the Nazi regime and the impact of World War II halted the adoption of the Frankfurt Kitchen in Germany, the postwar housing boom in the United States saw a surge of interest in space-saving, cost-efficient kitchen designs that drew from some of the ideas Schütte-Lihotzky pioneered. Today, a replica of the Frankfurt Kitchen is on view at Vienna’s MAK – Museum of Applied Arts, and the architect’s own kitchen in the 592-square-foot apartment she designed for herself in the Austrian capital, where she lived for the last 30 years of her life, is now meticulously restored as an apartment museum.

Top photo by Bettina Frenzell via Margarete Schütte-Lihotzky Zentrum

—

Published

Topics

LifestyleGet the Dwell Newsletter

Be the first to see our latest home tours, design news, and more.