The Circuitous Journey of an Early Prototype for U.S. Affordable Housing

Welcome to Origin Story, a series that chronicles the lesser-known histories of designs that have shaped how we live.

The Aluminaire House started with a small budget and a big dream. Architects A. Lawrence Kocher, a longtime Architectural Record editor, and Albert Frey, a former apprentice of Le Corbusier, designed the full-scale model as a case study for affordable houses that could be mass-produced quickly without sacrificing style. Today, the country’s first all-metal prefabricated house is considered a modernist masterpiece, one that brought International Style—already popular in Europe—to the United States. (The design was later included in the seminal book The International Style: Architecture Since 1922.) But in the decades since it was constructed, the prototype house has had a rough run, facing multiple relocations and periods of disrepair. This spring, the Palm Springs Art Museum will become the structure’s permanent site. These are the details of its long journey to its final home—and what it cost to get there.

An affordable case study

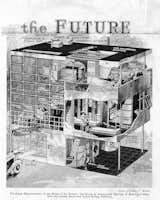

Debuting in 1931 as part of a special exhibition cosponsored by Allied Arts and Industries and the Architectural League of New York, the Aluminaire House was built in just 10 days, using prefabricated materials donated by national manufacturers. The three-story block with ribbon windows was framed in aluminum and steel and supported by six slender aluminum columns. The architects designed built-in furniture, like a retractable dining table, beds suspended from the ceiling using metal cables, and inflatable rubber chairs. Frey and Kocher estimated that if enough people purchased an Aluminaire House, each would cost less than $3,000 to build.

So…who wants to buy it?

More than 100,000 people toured the prototype, but then it had to go—it was allotted only one week at the Grand Central Palace exhibition hall. Enter architect Wallace K. Harrison (a notable modernist in his own right—he led the design of the UN Headquarters, working with Le Corbusier and others), who reportedly paid $1,000 to have the house moved from Manhattan to his Long Island estate, where it was reassembled. During the next decade, Harrison tinkered with the original structure, turning the first floor into a basement and enclosing the roof terrace. The following year, images of the house were included in the first exhibition on architecture at New York’s Museum of Modern Art, curated by Philip Johnson and Henry-Russell Hitchcock.

A house in need of a home

When Harrison’s estate was sold in 1974, it was listed on the National Register of Historic Places, but the Aluminaire House wasn’t. A decade later, the estate was sold to new owners, who sought to demolish the house because it had fallen into disrepair. (A Newsday reporter who visited the house for a 1987 article noted graffiti on the walls, champagne bottles on the floors, and rust creeping into the metal joints.) Architecture buffs united to save the house, and by 1988 it was moved to one of the sites of the School of Architecture and Design at the New York Institute of Technology (NYIT), thanks to two grants from the New York State Office of Parks, Recreation and Historic Preservation.

A permanent address

Over the next roughly two decades, funding the project was difficult for NYIT, and when the architecture program was relocated, it was yet again time for the Aluminaire House to move. In 2014, the Aluminaire House Foundation looked to Palm Springs—an apt choice, considering its close associations with Frey’s brand of modernism. After years of sitting disassembled in a shipping container—first waiting for a relocation site, then for the go-ahead to be rebuilt—the Aluminaire House opens March 23 in its permanent site at the Palm Springs Art Museum. The total cost of the structure’s moving, restoration, and reassembly is expected to reach $2.6 million—a far cry from the affordable vision that inspired the house, but a pretty good deal for a Frey original.

Top rendering by Claudia Cengher, courtesy Palm Springs Art Museum

—

Published

Last Updated

Get the Dwell Newsletter

Be the first to see our latest home tours, design news, and more.