An Architect Revives a Dreary, Prefab A-Frame Cabin in the Hamptons for $300K

Architect Edgar Papazian and his wife, Michelle, weren’t immediately sure how to make the dilapidated A-frame cabin they’d purchased in Sag Harbor, Long Island, more comfortable for their family of four. "When we purchased the cheapest house in the zip code, it was simply shelter after a tumultuous period," says Edgar. "As we lived in it over the next year, I was able to examine the carcass of the thing we had bought and gradually figure out how it could work better for us."

Before the renovation, the non-winterized cabin—which was fancifully described by the real estate listing as a "chalet"—had been used as a summer vacation home. The renovation needed to make it suitable for a full-time residence to house architect Edgar Papazian, his wife Michelle, and their two young daughters.

"The ease in having yourself as a client is offset by the limitations you impose on yourself financially and emotionally," says Edgar. "Your own home is a place created as an extension of your identity, but it also has to fulfill practical functions—and I found I had to edit myself mercilessly. We also happen to live in a place where construction is very expensive, which made this build incredibly challenging and nerve-wracking."

The home is perched on the side of a large hill that hugs the coastline of the Peconic Bay; the beach is within short walking distance. "The house is nestled in a wood of small oak trees, and from certain angles appears to be perched in the canopy," says Edgar. "This idea is reinforced by views from the main level of the home to the north, in which only leaves can be seen."

The existing porch at the front of the home, which functioned as a main entrance, was removed. Now, a newly built timber footbridge leads to a new entry vestibule at the side of the home. This footbridge wraps around the house to form an additional deck at the rear which can be accessed from the main living area.

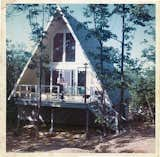

The home was built from a kit in 1965, and had been in the same family ever since. When the Papazians bought it, it hadn’t been updated in some years, and there was a partially finished basement project that had been abandoned. With no insulation or modern mechanical systems, it was also drafty and chilly.

A photograph of the kit home when it was first built in 1965. "We built upon the language and the history of the home, which we learned about from neighbors and the local village as we lived in it," says Edgar. "I love that the son of the original owner has taken a real liking to what we have done—he has even provided us with all the original documentation, bills, notes, surveys, drawings and the catalogue they chose the house out of. To me they are part of the house."

"It had a little rabbit warren of bedrooms on the main level with an unsatisfactory living area, a ridiculous stair to a dreary loft, and a tiny galley kitchen with virtually no counter space, and a scary stair to the rear yard from the rear deck," says Edgar. "We called it our New York City apartment house owing to its layout."

Edgar referred to several precedents when working on the renovation. "I love Chad Randl’s book on the A-frame typology, which allowed me to understand what I had on my hands with its copious illustrations and drawing documentation," he says. "The lovable architect Andrew Geller did at least two seminal A-frame homes during the midcentury in the Hamptons, the Betty Reese houses I and II. I took the catwalk notion from Reese house II."

Because the budget for the renovation was so tight, Edgar ruled out the option of expansion from the beginning. Instead, he rearranged the entrance and living space, added a series of mezzanine levels, and finished the basement.

On the main level, a poorly constructed winterized porch—which functioned as the main entry—was removed and a new entry was created by building a small cedar footbridge from the road. This doubles as a modest deck that overlooks the rear of the property. An entry vestibule leads directly to the main living area, where all the interior partitions were removed to create a combined living and dining space with a triangular projection that contains a kitchen and small bathroom.

The original floors were "horrible" laminate, says Edgar. During the renovation, they were replaced with Douglas fir timber flooring that matches the timber structure of the home. The kitchen cabinets are sapele timber, and a cost-effective timber-effect laminate has been used on the kitchen countertops.

A series of mezzanines was created above this space to provide a retreat, as well as a home office for Edgar’s architecture practice. "As I was concerned about maintaining the wholeness of the space, I took pains to construct the lofts and catwalk with spaced Douglas fir boards to allow light and air to circulate," he says. "This was the last part of the renovation, and we were most financially depleted at that point—but it had to be done to make the interior space work, and I’m so glad we did it when it hurt the most."

Shop the Look

From the beginning, Edgar knew he would need to finish the partially completed basement, which had tall ceilings and access to good natural daylight, to create enough space for his family. The existing basement only had access from outside, however, and one of the main challenges was to create circulation within the interior of the small home to provide internal access to the downstairs living area and bedrooms.

A spiral stair at the center of the living space leads downstairs to the lower "basement" level. The small spiral stair was the only solution for code-compliant vertical circulation in a house with such a small footprint. The alternative would have involved building a "saddlebag" onto the side of the house to create a traditional stair run, which would have exceeded the budget.

"The solution was the smallest code spiral stair we could manage between levels, in the dead center of the house," says Edgar. This new lower level has three bedrooms on the corners of the foundation, a bathroom, utility closet, and a cozy family room at its heart.

The total cost of the renovation was around $300,000. "For the Hamptons, this is a rounding error on any typical project," says Edgar. "I added a tremendous amount of sweat equity to the project, mostly finishing and anything unskilled, when I wasn’t working in my then full-time job."

Throughout the renovation, Edgar was committed to retaining the history and essence of the original home. "We didn’t want to literally whitewash the history and original finish of the house, which was the 50-year-old, UV-exposed, Douglas fir tongue-and-groove boards and built-up rafters of the kit," he says. "So, I chose to work with the original palette of aged Douglas fir."

In areas where the use of timber was cost-prohibitive, the architect made "slightly tongue-in-cheek" use of fake woods. For example, the cost-effective laminate on the kitchen countertops that mimics layered wood, or the ceramic tile with wood pattern and color employed in the bathroom.

In the basement, Edgar employed light-colored walls to bounce as much light around the space as possible, and structural grade Oriented Strand Board (OSB) for the floors. "It’s derisively called ‘snot board’ in the industry," he notes. "But, it is a durable, visually pleasing solution that has aged very well."

To make the home more thermally comfortable and energy efficient, eight inches of insulation was added to the roof, which is finished in yellow cedar shakes—a thicker alternative to shingles. The eaves of the house are painted in Outrageous Orange by Benjamin Moore, referencing the orange elements in the main living space.

"The renovation coexists with the existing home, without trying to overly differentiate or slavishly copy the original," says Edgar. "It creates a new-old hybrid structure, with the new working alongside the old without pretending it’s still 1965. I view this project as a historical restoration, of sorts, for our time."

A 1970s A-Frame Cabin in Big Bear Is Brought Back to Life

Project Credits:

Architect of Record: Edgar Papazian Architect LLC

Builder: Building Arts LLC

Structural Engineer: Edward Armus Engineering PLLC

Photographer: Lincoln Barbour

Published

Last Updated

Get the Dwell Newsletter

Be the first to see our latest home tours, design news, and more.