The Country's Best Yurt

Yet our houses remain models of permanence. Whether we sleep in bungalows, brownstones, or ’50s-era ranch houses, we don’t uproot them when we uproot ourselves. Put quite simply: Our homes don’t reflect our habits.

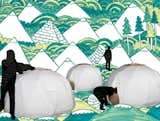

Enter the Nomad. Modeled on that 2,000-year-old stalwart of transience, the Mongolian yurt, or ger (rhymes with "air"), the Nomad is Ecoshack’s modernist update on the Cadillac of tents.

Stephanie Smith founded Ecoshack—whose projects have included a solar-powered beekeeper’s hut made of recycled bee boxes—on a few acres just outside Joshua Tree National Park. It began in 2003 as a design studio, informal testing facility, and lifestyle think tank for designers, architects, inventors, and artists, and has since expanded to become a Los Angeles–based design studio and manufacturer.

Smith’s past collaborations have included big names like Reebok and IKEA, but her abiding interests run toward community. She investigated China’s cultural adaptation to globalization while at Harvard’s Graduate School of Design. She studied under, and later went to work for, Rem Koolhaas, but after spending time at Arcosanti—Paolo Soleri’s experimental, ecologically minded, "arcologist" city some 70 miles outside Phoenix—she committed herself to bridging the gap between the fringes of design and the culture at large.

"On a trip out to Joshua Tree I happened upon a shack," she says—a description that, it turns out, is totally apt—"fell in love with it, found out who owned it, offered him cash, and was in escrow a few days later. I realized that the high-desert area today looks a lot like what I imagine Palm Springs looked like 50 years ago: a place where extreme conditions trigger new ways of thinking about dwelling and lifestyle." After holding a design competition for a sustainable camping structure and doing several custom designs for clients, she started thinking about the hardy herders’ home as architectural product.

"There’s a healthy niche market for yurts," Smith tells us. "But they’re either copies of Mongolian yurts, or made in the traditional way out of new materials. I saw a chance to innovate, particularly in terms of modernizing the design and greening the materials." Her view of how to use the yurt, meanwhile, is dis-tinctly old-fashioned. "People in America are more likely to use their yurts in a permanent way, on roofs or in backyards. I wanted to get back to the nomadic yurt. That’s really the genesis of the Nomad."

Traditional yurts use a fairly complex lattice framework, a platform that often has to be built anew each time the yurt is moved, and a central tension ring holding it all together. The Nomad’s design is much simpler and more easily assembled. The wall and roof structures are combined into one single frame made of bamboo—an abundant, light, and remarkably strong wood. "The bamboo all comes from Vietnam and is fashioned there by local artisans," Smith explains. "We tried to get it all made closer to home, but commercial bamboo is a strictly Asian affair." The ring and platform are made of plywood, so there’s no need to forage for a new one every time. They come in a modular kit, and the platform’s 12 pieces lock together to form a hexagonal base. You can also have your platform’s surfaces done with a plyboo (that’s bamboo plywood, naturally) finish. Ecoshack also replaces the yurt’s traditional felted wool covering with WeatherMax, a sustainable outdoor-use fabric that’s breathable and water repellant.

Ecoshack has more in mind, though, than simple aesthetics. "My mission, if I have one," Smith adds, "is to facilitate and cultivate green experiences in nature. Small structures help realize that. When you’re out in the desert in a yurt for three nights, something happens."

Published

Last Updated

Get the Dwell Newsletter

Be the first to see our latest home tours, design news, and more.