How Green Construction is Significantly Cutting Emissions

It’s a sad reality that when people parse the numbers on climate change, it rarely results in positive news. But ask architect, educator, and activist Edward Mazria about the building sector’s remarkable turnaround on emissions, and you’ll get a different story. During speeches at the AIA Convention and recent climate talks in Bonn, Germany, he told the story of how the construction and architecture trades have significantly cut emissions. Dwell spoke with Mazria about the new ways his organization, Architecture 2030, is advocating for and advancing green construction, and why architects are wired to make the world a better place.

The Payoff from a Greener Building Sector

Saving the environment also saves significant money. American consumers have spent $560 billion less on energy from 2005-2013 due to sustainable design and construction. Compared to projections from 2005, the EIA AEO 2014 put savings at $4.61 between 2013 and 2030 – or $6.55 trillion if best available demand technology is employed.

1) Structures like the new, solar-powered stadium in Brazil and the Bullitt Center in Seattle suggest environmentally sound buildings aren’t just theories—they can be built right now. How does the technology and the willpower to do this type of big construction funnel down to smaller scale building projects?

Just a few years ago, there was little discussion of zero-net-energy (ZNE) or carbon neutral design. We discovered that the building sector was the major contributor to the climate change problem, and the solution, in 2003. That was only a decade ago. We issued 2030 targets in 2006, seven-and-a-half years ago. At that time, they seemed to be a bit aggressive, but today the targets are set at a 60% building energy reduction. All of a sudden, you’re seeing ZNE discussed across the country, major conferences happening, and California moving, by code, to ZNE for residential buildings by 2020 and commercial buildings by 2030.

2) Are we nearing the crest of a wave, where building in this way becomes ingrained?

Yes, we’re going to see an explosion. Building codes are reducing energy consumption, and with a little design effort, you can reduce consumption even further. Then, you can get to zero by adding a modest solar electric and hot water system at a cost competitive with fossil fuel energy. Getting to zero isn’t that difficult today because of both energy codes and the affordability of solar and renewable energy systems.

3) How far have the aesthetics of green architecture come from when you started doing this work?

I don’t think there is a specific sustainable design aesthetic. There are many aesthetics, they reflect the times and evolve as times change. When you see a green wall, you think sustainability, but that may, or may not, be a sustainable building element. There’s a host of possible sustainable building elements—from where you locate glass, how you admit daylight into a space, glazing size, materials, surface colors, and textures—that are not really an aesthetic, but become part of the aesthetic you create. Our image vocabulary shapes the way we design built environments, which is why we developed the 2030 Palette as a highly visual language of sustainable design, a universal visual language, so to speak.

The idea behind the site was to create a platform or a framework for sustainability across the entire spectrum of the built environment. With the 2030 Palette, we're curating best practices—from large-scale regional planning issues, down to individual buildings and building design elements. These are tied together into action items that can be applied when planning or designing sustainable environments.

4) How can we convince more architects and designers to design sustainably?

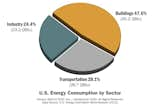

We must create a can-do attitude. There are so many designers realizing amazing works, what is needed is to stitch it all together into a sustainability framework. The U.S. building sector is a global success story. Emissions from the building sector peaked in 2005. Between 2005 and 2013, we added 20 billion feet to our building stock, but total energy consumption in the sector is on a downward trend.

Today, the U.S. is the second largest emitter of greenhouse gasses (GHG). We are responsible for more emissions cumulatively, than any other country, so we have an obligation to lead. When we presented the emissions reduction trend in the U.S. Building Sector at the AIA Convention, and at the recent climate talks in Bonn, many people were stunned. The world is looking for answers and solutions to the climate crisis, and all sectors must participate. Today, China and the United States are the two major GHG emitters, and when you look at where a majority of building construction will take place in the next two decades, it’ll be in China and North America; a great opportunity to affect change.

5) Your contribution to the famous Architects Pollute cover story in Metropolis really inspired the architectural community to act.

It’s ingrained in the professional architecture and planning community to make the world a better place, it is our responsibility, our calling. Our entire education and training is to bring places to life, make them better, functional, sustainable, and a positive addition to our world; a very utopian kind of education. When architects received that Metropolis issue with its provocative cover, there was an initial uproar. Once it settled in, there was a bit of soul searching, this is not what we do. We do not consciously pollute, everything completed prior to that issue was unintentional. However, now that our community understands the consequences of our designs, we took up the cause with fervor. When we issued 2030 Challenge targets in 2006 – getting to carbon neutral by 2030—within 30 days, the AIA adopted the targets and subsequently established the 2030 Commitment.

Many said meeting the 2030 Challenge targets would cost too much, cost jobs. Well, we’re not only meeting the targets, we’re ahead of the targets nationally, and it hasn’t cost anything! In fact, from 2005 to 2014, we have saved the American consumer hundreds of billions of dollars from what they were projected to spend on energy over this period. The U.S. didn’t lose jobs over it. All of this talk was nonsense, intended to keep the status quo.

6) You’ve said that architects have the power to change the way buildings are proposed and built, and really control the environmental impact. Is there a role for the government?

The government’s role is linked to codes, research, and incentives, and to lead by example. I can state as a fact, the fossil fuel industry does not want to see the government in a leadership role, designing and renovating their buildings to carbon neutral. They may be able to influence legislation and elections, but they can’t control how we—architects, designers, and planners—design.

Published

Last Updated

Get the Dwell Newsletter

Be the first to see our latest home tours, design news, and more.