Four Walls and a Screw-Top

Ask Roger Scommegna about the inspiration for the Aperture House, the eye-catching weekend retreat that he built on the sloping, grassy banks of Moose Lake, Wisconsin, and he cites an improbable source. The idea, he explains with a straight face, came from a squat, screw-top jug of inexpensive red wine.

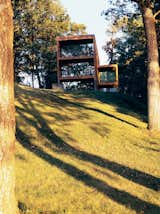

On the shores of Moose Lake, Wisconsin, the inspiration for Roger Scommegna’s Aperture House came from the $9.99 bottles of wine produced at his Signal Ridge Vineyard.

In 2001, Scommegna cashed in his earnings from Realtor.com, an online compendium of real estate listings that he helped launch during the dot-com boom, and invested in a pair of vineyards in Mendocino County, California. A year later, Scommegna’s fledgling Signal Ridge Vineyard scored an unlikely hit with Three Thieves, a screw-top zinfandel with a bright red label and a retail price of $9.99.

A comfy set of nine interlocking orange throw pillows from Roche Bobois fills the downstairs television room.

The surprising success of Three Thieves gave the 42-year-old Scommegna an idea. If a good wine could be mass-marketed in an unassuming package at an affordable price, he reasoned, perhaps the same could be done with architecture. A narrow, 50-foot-wide lot that Scommegna purchased at Moose Lake, about 25 miles west of Milwaukee, would serve as the proving ground.

Each of the house’s three sliding patio doors was positioned to frame panoramic views of Moose Lake, so it was important that the furniture wouldn’t get in the way. The pieces chosen were just right: A low-lying couch and armchair, both by Luminaire, hug the living room floor. A square coffee table, also by Luminaire, sits less than a foot off a blue shag rug.

Scommegna pitched the idea to Vetter Denk Architects, the forward-thinking Milwaukee firm he had hired in 1995 to design his primary residence in Brookfield, an upscale Milwaukee suburb. "I said, ‘I want to build a home like this wine,’" Scommegna recounts.

Backless picnic-style benches stand in for chairs at the refinished Milwaukee Public Library table where the family eats their meals. The sofa and armchair are from Luminaire.

"‘Simple packaging, and nothing fancy, because this is a screw-top jug. But I want good design, and I want it to be a surprise when someone opens up the wine or comes in the house.’ I just kind of wanted it to be quiet on the outside, big surprise on the inside. And then I left them with this bottle of wine."

With Three Thieves, Scommegna set out to debunk the conventional wisdom that wine can only be good if it’s corked in an expensive bottle. The challenge that architects John Vetter and Kelly Denk set for themselves was to prove that a house could be quickly constructed from prefabricated parts and still be tasteful and architecturally daring.

The kitchen cabinets where the Scommegnas store their dishes are open, creating what Vetter calls a "nonfussy, more direct approach to the storage of your daily items." Scommegna allows that a pair of doors easily could have been added without much trouble. "But then you’ve got to open it every time you need something," he says. "It’s just dumb. What are you hiding? They’re just plates."

Ten days later, Scommegna returned to Vetter Denk’s downtown Milwaukee office and was shown a cardboard model that, he says, "looked like three shoeboxes stacked on top of each other. As always," he continues, "I needed to process it for a minute."

To help keep the house free of clutter, the full-size refrigerator was hidden in a basement utility room. An unobtrusive three-foot-tall fridge and matching freezer—made by Sub-Zero—were tucked beneath a kitchen countertop. "There are so many more options with refrigeration, and under-the-counter is really great," says Vetter. "You free up space and don’t have this big, clunky thing sitting there." www.subzero.com

It didn’t take long for the architects to sell Scommegna on the idea. Vetter and Denk planned the house along a regimented, four-by-four-foot grid that helped keep construction simple while allowing for limitless variations that could be adapted to any site.

They hired a local carpenter to create the 8-by-20-foot exterior wall panels from prefinished cedar plywood. The exterior panels, flooring components, and Parallam support beams (not unlike a plywood I beam) were all manufactured offsite and hauled to Moose Lake on flatbed trucks in March 2002. The building’s shell was assembled in less than 48 hours.

"The concept was to use prefabricated technology that for the most part has been used only to achieve low cost," Vetter says. "Prefab has a negative connotation, a stigma. This is an opportunity to shift the paradigm and use the same technology to do these nice little pieces of architecture. That’s what the Aperture House is all about."

The filmic designation of "Aperture House" came from the patio doors framing panoramic views of the lake. Vetter, Denk, and Scommegna worked hard to keep the house free of clutter and not to interfere with those views.

Bathrooms were relegated to the basement and upstairs. There is a full-size refrigerator, but it’s hidden in the basement utility room. A mini-fridge and matching freezer sit unobtrusively beneath a kitchen counter, and food and drinks are carried up from the basement as they are needed. "The whole concept was to be able to walk in the front door and see through the entire house to the lake," Scommegna says.

Because the Aperture House was conceived, in part, as a dry run for a national effort to bring affordable, high-end architecture to the mass market, Vetter and Denk had to find innovative ways to keep costs down without sacrificing taste.

The house’s interior walls are medium-density fiberboard, the sort of material that more typically is covered with drywall. Instead, the fiberboard was coated with a linseed oil to accent its natural, rich tan and finished with a catalyzed var-nish to make it water-resistant. The effect is an interior wall surface that complements the earth tones that dominate the house’s decor and never needs to be painted.

The interior walls, doors, and cabinets, for example, were made from finished medium-density fiberboard, a material that typically is hidden beneath drywall. Instead of having large, floor-to-ceiling windows custom-made at great expense, the architects framed the views of Moose Lake in conventional sliding patio doors.

Similarly, the floors were done in utilitarian concrete, covered here and there with shag rugs. Using a process called "integral color," the concrete company added colored powder to the mix, infusing it with a sandy tint that complements the house’s earthy decor.

Scommegna says that, too, was part of the concept. "I’m hoping that when you are sitting here you get the feeling of simple, that you don’t get the feeling of fussy," says Scommegna, who spends most weekends at the Aperture House with his wife, Pamela, 42, and daughters Nicole, 17, and Krissy, 14. "We don’t want to be fussy here. We want the kids to walk in with their Aqua Socks, drip water on the floor, and sit right at the picnic table here, and I sincerely mean that. It’s literally designed not to be fussy."

Last May, the Aperture House earned Vetter Denk an honor award from the Wisconsin chapter of the American Institute of Architects. Since then, the firm has forged a partnership with a leading manufacturer of modular homes, and they are in the early stages of an ambitious plan to bring the Aperture House concept

to the suburban mass market.

The Aperture House itself, which cost more than $300,000 to design and build, is more "tweaked out" than its progeny is likely to be, Vetter says. The idea is to get the list price near $199,900. Scommegna calls that price the "sweet spot," a term he also uses for the $9.99 price tag of his wine.

"We still have to fit in people’s heads," Scommegna says. "I don’t think this home fits in people’s heads for mass production. But the concept is there and our partner is going to be there, and the design will be there."

Vetter is confident that the concept will translate easily to suburbia. "It’s a little house," he says. "It does everything you need it to do. It does it humbly, with nature, and it’s fun. You don’t need anything else. It’s perfect."

Published

Last Updated

Get the Pro Newsletter

What’s new in the design world? Stay up to date with our essential dispatches for design professionals.