Studio:Indigenous Founder Chris Cornelius Is Decolonizing Architecture

A citizen of the Oneida Nation of Wisconsin, architect and educator Chris Cornelius has worked relentlessly to expand Indigenous sovereignty in the field. He’s the founding principal of Studio:Indigenous, a design and consulting practice serving Indigenous clients, and teaches a course called "De-Colonizing Indigenous Housing" at the Yale School of Architecture. Cornelius’s teaching and design career straddles both Canada and the United States, defying traditional notions of borders as boundaries.

Among his many accolades, Cornelius was among a group of Indigenous architects who represented Canada in the 2018 Venice Architecture Biennale, and he was a design collaborator on the Indian Community School of Milwaukee (ICS), which won the 2009 AIA Design Excellence award from the Committee on Architecture for Education. His 2019 lecture at the University of Arkansas, "Make Architecture Indigenous Again," elevated Indigenous values in contemporary architecture and drew upon his 2003 Artist in Residence Fellowship from the National Museum of the American Indian at the Smithsonian Institution in Washington, D.C.

Cornelius is known for such works as trickster (itsnotatipi), a temporary installation in Sheboygan, Wisconsin, and Wiikiaami in Columbus, Indiana, a piece inspired by the dwellings of the Miyaamia people indigenous to Indiana. For Cornelius, every structure starts with a story. His passion for drafting comes to life when using Indigenous narratives to inspire physical spaces that pay homage to heritage, while respecting the natural landscape. As an architect and educator, Cornelius pushes the boundaries of what we consider architecture and increases representation for native people in the field.

How did you know that architecture was your calling?

Cornelius: I think I always knew I wanted to be in architecture, even before I knew exactly what it was. I was fascinated with building. My father was a brick mason, and I became intrigued by the fact there was someone who designed the things he was building. In particular, I was interested in the drawings. By the time I started high school, I knew I wanted to be an architect, and everything I did was moving toward that goal. I took every drafting class I could. I even competed at the local and state level in vocational competitions for drafting by the time I was a senior.

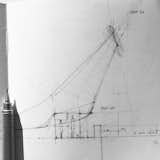

Is drawing the root of your design process?

Each project is unique, but most projects start by drawing ideas. I think it is important to start drawing even before you know what it is going to be. I like to start with stories and find ways to draw—not illustrate—through the story. There is so much content in Indigenous stories, science, history, technology, architecture, ecology, etc. I believe architecture should have as much content and serve as a tool of conveyance for sharing those things with all living things, as our relatives.

You’ve been an academic-practitioner for many years. How do you incorporate ecology and Indigenous history into teaching architecture?

Indigenous knowledge has always contained ecology and history. I try to teach my non-Indigenous students in the same manner. For my studio at Yale, I gave students a series of readings that were about Indigenous history, policy, ecology, storytelling, and research paradigms. What I realized in that process is the more I taught them about Indigeneity, the more they realized what they didn't know—and it wasn't their fault. Their K-12, undergraduate, and partial graduate studies had taught them nothing about Indigenous history in the U.S. and Canada. This wasn’t a shortcoming on their part, but a failing in the system of colonized knowledge.

Because I tried to expose them to more Indigenous thinking, I believe our conversations about architecture became enriched by why it was important to think of our other living relatives or why exercising Indigenous sovereignty, whenever possible, is imperative.

The model of architectural education which has been in existence for about 150 years is very good at teaching students about the what and the how of architecture. It has failed students by not teaching more about the who and the why. I am trying to change that as an educator.

What has it meant to you to mentor young architects and designers, and to serve Indigenous clients through your studio?

Being a professor of architecture is a gift. The best students are ones that seek mentoring, and it was an important part of my own maturation as a designer and educator. I can enjoy watching the development of students at my Yale Studio, like Max Wirsing and Ruike Liu.

I have also been fortunate to connect with Indigenous students of architecture (most are in Canada) and try to advise them as much as I can. I hope the workload for Studio:Indigenous will continue to expand. This is the only way for me to take on some of these individuals as employees.

When I started Studio:Indigenous in 2003, I did not see many Indigenous designers serving Indigenous clients. It's not that there weren't any, I just wasn't aware of them. I decided to start my practice to serve Indigenous people because, in my experience, design had not served them well, and I wanted to change that. This meant not specializing in any type of project, but to find the best way to translate the culture into an architectural experience.

What needs to happen now in design and architecture to address the realities of this current moment?

We need to start including different voices in the conversation. This must happen from the top down—and bottom up. We need leaders from groups we haven't seen before. We need people in the design disciplines from groups we haven't typically heard from. We can't just stay in a world of reading lists and resource guides. We need to lift people into leadership roles, faculty positions, firm principals, governing positions, policy makers, client representatives, etc. I think our students (and not just students of color) are demanding it. The people controlling the funding mechanisms need to examine the ways they have always supported and/or fostered white-only mechanisms. I think most have done it unknowingly and unintentionally.

How does the built environment interact with Indigenous history?

The built environment is Indigenous history. This relationship is sordid and complex.

We start with an understanding that if we are intervening in this landscape, we are intervening on Indigenous land.

Most U.S. cities are founded on Indigenous settlements. This land was not a "wild frontier" when European colonizers arrived. It was a complex network of civilizations that saw themselves as stewards of the land. This land was managed, maintained, and cared for like a relative that needs assistance. The built environment should not be seen as different from the non-built environment. It is all one robust family that we, as designers, facilitate interaction between key elements.

I believe that all design schools should require Indigenous history and policy courses. I think every design student should know the 1887 Dawes Act as well as they do the U.S. Constitution. Site analysis and history shouldn’t start with when a place became a city or state, but with the people indigenous to that landscape.

Decolonization starts and ends with addressing the dispossession of lands from Indigenous people in the U.S. and Canada. Colonized thought would want us to build and continue the differences between each of us to keep us apart. I believe true decolonization starts with the realization that colonization is fueled by a lack of empathy.

We can begin to dismantle the apparatus of colonization by incorporating empathy into the methods and strategies we use in design.

Published

Last Updated

Get the Pro Newsletter

What’s new in the design world? Stay up to date with our essential dispatches for design professionals.