Building the Maxon House: Week 6

Week Six: Visiting Olson Kundig Architects

I spent the months between our initial phone call and my first meeting with Tom Kundig familiarizing myself with his extensive portfolio of work. I scanned the website, re-read and bookmarked different portions of his book and browsed the numerous magazine articles the firm had sent over. I looked for projects of similar size, scope and setting in order to gather thoughts to share, questions to ask and details to discuss. As I made my way up to the sixth-floor offices of Olson Kundig Architects in March 2008, I was honestly nervous, inspired and slightly intimidated.

Located in the historic Washington Shoe Building in the Pioneer Square Historic District, the office design limits its impact on the preexisting space. The open plan layout is pulled away from the perimeter walls to limit contact with the existing historic structure and to take advantage of better natural daylight, circulation paths through the office, and to avoid the favoritism associated with the "corner office." Sustainable ideas were explored through the natural ventilation strategy (skylight and open stair for a chimney effect), not painting the warehouse walls or even the old windows (left "as is"), using masonite for floors and walls (a highly recycled content material left unpainted), and unpainted steel. Photo by Benjamin Benschneider.

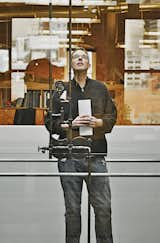

Recognized for his seamless integration of architecture and landscape, Kundig’s projects are unique in their meticulous attention to detail and in the materials used, which are often left in their natural, raw state. His igenuity is evident in the experiential nature of his work, in his use of kinetic architectural features and in his reinvention of structural elements that are often overlooked. Photo by Tim Bies/Olson Kundig Architects.

The Brain is a 14,280 cubic-foot cinematic laboratory where the client, a filmmaker, can work out ideas. Physically, that neighborhood birthplace of invention, the garage, provides the conceptual model. The form is essentially a cast-in-place concrete box, intended to be a strong yet neutral background that provides complete flexibility to adapt the space at will. Inserted into the box along the north wall is a steel mezzanine. All interior structures are made using raw, hot-rolled steel sheets. Photo by David Wild.

Sixth floor. Ding. The doors slide open. Here I go.

I waited patiently in the lobby after being greeted by the receptionist. It was raining outside. The clouds were dark. It was your prototypical Seattle afternoon.

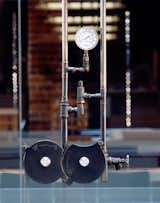

The offices take up two floors of the brick Washington Shoe Building in the Pioneer Square neighborhood of Seattle. A steel staircase takes you downstairs, while a genius Kundig gizmo hovers overhead: a hydraulic powered skylight that operates with the turn of two wheeled handles. The counter of the lobby reception area was carefully curated with books and articles championing the firm’s range of work.

As I scanned the office from the lobby area, I glimpsed a myriad of scale models (maquettes) taking over the office’s shelves and counter tops. I’d visited quite a few architectural offices by now, but this was a cathedral by comparison. What first surprised me was the lack of enclosed offices (Tom Kundig works in a plywood cubicle!). If the initial feel and impressions of the offices were an indication of what was to come I felt pretty good. Modern architecture is sometimes deemed cold and impersonal, but this space was sublime. Warm, open, comforting and beautiful, with no detail overlooked. I felt at home. So far, so good.

Tom walked over and introduced himself and we soon settled into one of the conference rooms. An oversized pivot wall/door gently slid closed behind us and we started chatting. We’d covered a lot of ground over the phone so we started getting into more detail on the future residence. There seemed to be instant chemistry picking up from where we’d left off on the phone.

Tom would listen intently then burst into ideas about the house. He shared stories and inspirations from other projects and experiences, connecting them to the opportunities he saw in our future dwelling. He was as kinetic as the architectural engineered gizmos he was known for.

We talked a lot about the site, about our expectations and about his overall architecture and design philosophies. The focus for us was going to be simplifying the actual volume (shape of the building) so that we could leave room and budget for some fun detailing.

There are signature elements to every Kundig project, and I wondered as we talked what would make its way into our project—hoping that we’d allow enough budget and, more importantly, enough creative leeway to Tom and the firm to explore and imagine some functionality. We had to be very disciplined on the construction and design budget, so Tom recommended we keep the team working on the project very small, limited to himself and a project manager/architect. I’d be the representative from our family—the point of contact for communicating questions, issues, and concerns along the way.

We talked a bit about the scope of our project, and the "program" for the house. I wanted a main residence for a family of five, some sort of garage or area for cars and storage, and a studio or office space to work in, separate from the main residence. I was particularly drawn to the Brain studio that he had designed for a director, and he shared a couple of other projects, including a concept for a room that moved on rails. This was wild, I thought. The office space was an additional opportunity to take some risks. I was ready to go there.

After about an hour of our discussion and some initial brainstorming, our time was up. There was still a lot to discuss; we’d barely scratched the surface.

Meeting Tom Kundig gave me 100% confidence that our decision to reassess and go after what we really wanted would pay off in spades. He mirrored everything we had read and was even more impressive in person. I left the sixth floor that day with a heightened sense of euphoria and inspiration, my nervousness gone. Tom and I were on the same page. I had the sense this was going to be a wonderful journey.

Published

Last Updated

Get the Dwell Newsletter

Be the first to see our latest home tours, design news, and more.