Building the Maxon House: Week 5

Week Five: Finding Architecture Nirvana

It was late 2007, and we had just wrapped up interviewing design-build firms, architects, and prefab companies—but nothing seemed to resonate. Having just spent a sizable chunk more on the land than we had previously planned, we also had to reset our expectations when it came to finances.

Our biggest milestone to date was the acquisition of our land. The quest now was to find the architect who could leverage the site benefits and the needs of our family—and do it all within a budget that made the project doable for the near future.

We’d hadn’t originally taken into consideration the costs for surveys, geotechnical drilling, structural engineering, architectural services and fees, outside consultants, forestry, clearing and grading, or county permits, for example. It was all adding up quickly, and we hadn’t even written the big checks yet. Most of these costs are out-of-pocket and paid in cash outside any loan—although some of these costs are later credited back in by the bank as pre-paid equity when applying for the loan.

The first step was to reset our budget to better reflect the real costs of our project. A third of our budget was tied up in the cost of the land. The remaining two-thirds we’d put toward the costs of architect-design plans and cost of construction.

We explored going back to a few folks with our newly adjusted budget, but in the end we agreed to a fresh start. Our original challenge was still intact: design a modern family residence on 21+ acres in a forested setting for a family of five.

The Most Expensive Coffee Book Ever

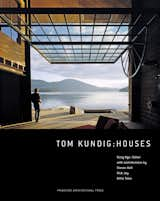

We received a bunch of architecture books for Christmas in December of 2007 but one turned out to be a game-changer—Tom Kundig: Houses.

I’d seen Kundig’s work in magazines and books but didn’t know enough about firm names or individuals to connect the dots. Most architecture books are house porn with beautiful visuals, but not a lot of details or context about the "why" behind the project. This book was different. I quickly became a fan.

The architecture seemed to be the sublime mix of past and present that we’d been looking for but almost given up hope to find. Kundig’s work seemed to be a perfect fit for not only our aesthetic tastes but for our site.

Obviously, seeing his work I wondered if this was even feasible financially and if the Seattle–based firm, Olson Kundig Architects—and Tom Kundig in particular—would be willing to take on our project. His work had been widely published in local, national, and international magazines.

A month passed, but I couldn’t get the work out of my head. The kinetic nature of his work was incredibly inspiring to both myself and my wife. The book became my new architecture bible. Each project was an object of desire: A concrete and glass box in the woods. A set of kinetic steel shutters. A dragon steel staircase. A wall of windows that lifted and opened up to the lake view with the turn of a wheel. It was architecture nirvana.

Hit Send

I remember the moment it all began. It was a typically windy and rainy evening in January. The kids were asleep, and I was in my home office trolling around www.olsonkundig.com, checking out all the different projects. I ended up on the contact page and started typing in our information: my name, our contact info and a brief synopsis of our story. I asked if our site, our family and our project was something Tom Kundig and the firm would have any interest in.

I knew this was a 100-percent high-risk, high-reward situation. The type of projects featured in Houses were not conservative by any means. They would require a leap of faith. I read in the introduction that Kundig appreciated that architecture was not a "money back if you’re not satisfied" type of deal. This intrigued me. The other takeaway from the book was the quote at the beginning: "Only common things happen when common sense prevails." We had the opportunity to take the safe route and we opted out. And opted in to Kundig.

Some time passed, and we heard nothing. I wondered if my message submittal was lost in the ether. Then we got a call in early Spring 2008.

The Call

Olson Kundig Architects had received the inquiry and we soon received a packet of information, tear-sheets (like case studies) on different Kundig projects from a marketing representative at Olson Kundig Architects. An initial phone call was set up, and when the phone rang months later I found myself speaking directly to Tom. I must have looked like a bee trapped in a box buzzing around my office on my cell phone. We talked for nearly 45 minutes.

We discussed the background, the site and the opportunity. It was clear to me early on that we shared similar beliefs on design principles in general (simplicity, honesty of materials, importance of site) and that I had done my homework online and in numerous readings of his book.

Our discussion left me abuzz. He seemed genuine. Authentic. Super-nice guy. A rebellious and genius spirit. Nothing like what I’d experienced from any other architects we spoke with. He sounded as though he felt just as fortunate and appreciative to work with us as we felt about working with him. I was impressed by the generous amount of time he took to answer questions and to get to know our project.

I was on cloud nine. Ecstatic that we had found someone we’d love to work with, and who sounded and acted enthusiastic about moving forward with us. Next step was an in-person meeting. Stay tuned!

I gathered that the couple we bought the property from did a little Edward Scissorhands job on the very narrow sliver of a view. Seeing the forest through the trees became a mantra for us as we engaged with county foresters and embraced forest practices.

Published

Last Updated

Get the Dwell Newsletter

Be the first to see our latest home tours, design news, and more.