How Blockbusting and Real Estate Profiteers Cash In on Racial Tension

As the most unpopular president in American history stokes suburban racism in an effort to gain a foothold for a failing reelection campaign, it’s worth revisiting another characteristic tool in the annals of what scholars of housing segregation have described as racial capitalism.

A predatory real estate practice, blockbusting leverages racial prejudice to drive white homeowners out of their neighborhoods and coerce them into selling their properties at low prices. Real estate agents and speculators situated a Black household on a block, then capitalized on expectations of declining home values, flipping the vacating homes to Black families to turn a quick profit. Within a short period, a neighborhood’s demographics would change, and the manufactured white flight depreciated prices further in a self-fulfilling prophecy.

Congress outlawed blockbusting as a part of the 1968 Fair Housing Act, but provided little enforcement. Real estate agents and banks continued to maintain—or to systematically break, when they saw an opportunity for profit—the neighborhood color lines. Racial steering was disguised by coded terms for projected risk like "inner city," "urban," and later, "subprime," cementing the underfunding of public schools and wealth stratification.

Other sinister real estate tactics soon followed: Once the Federal Housing Authority was mandated to provide low-interest loans to Black homebuyers, its guarantee of compensation for mortgage defaults led to innovative forms of exploitation. Speculators began chasing Black buyers; and because the number of properties available to African Americans was even lower than the generally short supply of housing, the industry had a captive market. It artificially inflated home values and sold properties that were beyond the means of buyers who had few other options.

The companies made money on the initial sales, and when the owners inevitably defaulted, they could retrieve mortgage insurance payments—then flip the house to another buyer, starting a new cycle. In the worst-case scenarios, the buildings suffered from serious deterioration. In other cases, the companies systematically defrauded would-be buyers with confusing land option contracts—wherein they pay a premium for the option to purchase real estate for a fixed price after a holding period— binding them to perpetual rent payments in lieu of paying down the principal on a mortgage.

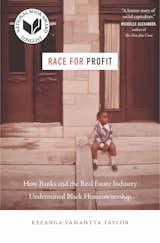

Keeanga-Yamahtta Taylor, author of Race for Profit: How Banks and the Real Estate Industry Undermined Black Homeownership, uses the term "predatory inclusion" to describe how African American homebuyers gained access to mortgages only on "more expensive and comparatively unequal terms," with poor conditions caused by "years of public and private institutional neglect" used as justification. "When redlining ended, these conditions of poverty and distress became excuses for granting entry into the conventional market on different and more expensive terms, in comparison with the terms offered to suburban residents," Taylor writes. "The result was the continuation of older predatory practices in combination with the invention of wholly new means of economic exploitation of African Americans in the U.S. housing market."

However, some scholars argue that blockbusting was a comparative net gain for Black households. Within tightly restricted housing markets that drove up the costs of shelter, it made more—and better-quality—housing available. From 1940 to 1980, African American homeownership increased by 27% in the U.S., though it still lags far behind that rate of white homeownership at 43% versus 70%. These homes did grow in value over time and allowed families to build generational wealth despite a relative devaluation in Black neighborhoods and unscrupulous practices by speculators.

Though blockbusting remains illegal, racial segregation and predatory lending practices still plague our most vulnerable communities. In the 2000s, with interest rates near zero and property values rising, creating the U.S. housing bubble, banks began offering adjustable-rate second mortgages so homeowners could cash in on the increase in home values. Then, the banks resold those subprime mortgages to hedge funds as high-risk securities, the speculators betting on the expectation that the loans would default. When the market crashed in 2008, the federal government bailed out the banks. Bankers, gambling against the homeowners, walked away with billions in profits while millions lost their homes. Black neighborhoods were left with foreclosed, deteriorating properties, and vacant lots where there had once been thriving communities.

The extent to which Black homeowners benefit from recent demographic changes—namely, the attraction of white buyers to historically African American neighborhoods—remains a source of debate among researchers and activists. In inflationary real estate markets like New York City, where late 19th-century brownstones have drawn white homeowners to neighborhoods like Park Slope, Bushwick, Bed-Stuy, Fort Greene, and South Harlem settled by African Americans during the era of white flight, prices can easily top one million dollars for an unrenovated two- or three-family home with well-preserved details. It can quickly rise to double or triple that price for a high-end conversion by design-savvy African American owners—or more likely, speculative white real estate investors—with access to capital, the fortitude to deal with contractors, and willingness to empty out existing tenants to appeal to upper-middle-class buyers.

All in all, the profiteering habits of the real estate market underline a need to rethinking housing as a commodity. Chris Tittle, staff lawyer and director of land and housing justice at the Sustainable Economies Law Center, which provides technical support for communities organizing to assert greater control over their resources, advocates for cooperative ownership and social housing that would permanently take buildings out of the speculative marketplace and place it in the hands of local groups and those in need of shelter. "When we’re doing work, our primary analysis is that the underlying root cause of a lot of this is the financialization of housing and the commodification of housing," Tittle says. "Housing under capitalism is not designed to providing housing for people; it’s primarily designed to extract as much value as possible."

Rent control, cooperative housing, community land trusts, the construction of new social housing, public banking, the elimination of restrictive zoning laws on multifamily housing, and subsidies for private investment are some of the ways that economists, design and planning professionals, activists, and policymakers believe the U.S. can remedy the unjust legacy of the real estate industry that have stripped African Americans of access to wealth and opportunity. Among them, the urbanist group BlackSpace is gaining prominence for its manifesto foregrounding African American voices in planning and design processes, centering the community’s needs and wishes in the shaping of places.

BlackSpace cofounder Peter Robinson’s recent workshops with urban designer Ifeoma Ebo in the Van Dyke public housing development in Brownsville, Brooklyn, found that participants viewed public housing as a multigenerational home they wanted to improve in lieu of the often unattainable goal of homeownership in New York City. "Throughout the entire experience of working in Brownsville, it was always the sense of people who we dealt with," Robinson says. "It was all about, ‘This is our home.’"

Given the history of cooperation between the real estate industry and the public sector in extracting wealth from Black communities through market-based processes, Keeanga-Yamahtta Taylor questions the premise of property ownership as a goal of federal policy, which insufficiently addresses the need for quality, affordable housing. The promotion of homeownership, she writes, represents an "abdication of responsibility for the equitable provision of resources" based on the "magical belief that homeownership will ever be a cornerstone of political, social, and economic freedom for African Americans."

Cover photo by Morning Brew via Unsplash

Published

Last Updated

Topics

Where We Live NowGet the Dwell Newsletter

Be the first to see our latest home tours, design news, and more.