Collection by Seth Biderman

lamesadevenn: Part Seven

In this series, trace the story of lamesadevenn, a green live/work space in Santa Fe, New Mexico, created for two community groups, La Mesita and La Resolana. Rather than simply becoming a building that addresses the structural needs of the groups, lamesadevenn seeks to embody their values of sustainability, experiential education, and community involvement. Part 7: Maya Tile.

The idea behind Maya Tile was hatched over a decade ago, when Antolewicz was working with glass artistry in the artist’s haven of Tesuque, New Mexico. At that point, she was mostly focused on learning how to blow glass, as shown in the images below. But she slowly began to get interested in a different way of working with glass, an ancient but uncommon technique called lost-wax casting. Often used by sculptors to create bronzes, Antolewicz discovered she could “cast” glass into smallish, square designs—aka, tiles. Photo by Amber Porter.

Today, Maya Tile’s a full-fledged business just outside Santa Fe, but it’s lost nothing of its originality. Each tile is a handcrafted work of art, an original Antolewicz, teased into creation through a multi-step process that begins when the artist carves a design into wax or clay. Clients can suggest design themes or images that will best work with their homes, or let Antolewicz work her magic. Photo by Bethany Antolewicz.

The tile is then framed and flooded with liquid rubber, which sets into solid rubber to create a master mold. This mold’s an inverted version of the original design—the sculptural equivalent of a photographic negative (remember those?)—and can be used to create several tiles. The rubber mold is filled with hot wax, which cools to create a clone of the original. The process is inexact, however, and Antolewicz spends plenty of hours hunched over these wax clones, detailing the design with a steady hand and very thin knife. Photo by Ryan Helean.

A second mold is then created, this time by setting the wax clone in a wooden frame, and filling it with a plaster mix the consistency of heavy cream. Once hardened, the plaster is removed from the frame, and the wax is steamed out. Keeping an eye on their environmental impact, Maya Tile often uses a solar oven for this steaming process, and always recycles the wax for future tiles. Photos by Ryan Helean and Celia Santos/Celia Luz Photography.

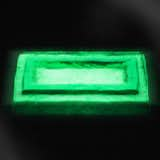

The emptied plaster mold is then loaded with exact measurements of crushed glass and slid into a kiln, roaring at 1,500 degrees Fahrenheit. When the glass has melted and cooled, the tiles are carefully pulled out of the plaster molds, and cleaned and polished around the edges. The artistic metamorphosis from clay sculpture to glass tile is complete, and the piece is ready for installation. Photo by Celia Santos/Celia Luz Photography.

As a founding member of lamesadevenn, Alba was intrigued by the unique history and process of Maya Tile. As an architect, he fell in love with the tiles. He invited Helean and Antolewicz out to the south side to check out the Rancho building. The couple understood his vision at once—a physical space that inspired crossing of genres and collaboration—and jumped at the chance to have a few of their tiles installed. Photo by Christian Alba.

And so was christened the entrance of Santa Fe’s most elusive architectural endeavor. Like so many other artists and architects, so many other writers and thinkers and alternative builders, Maya Tile stepped outside the conventional profit-based paradigm to offer a unique contribution to lamesadevenn. In the future, Helean and Antolewicz dream of using the building to teach other aspiring artisans how to cast glass. But for now, the tiles stand as a beautiful architectural accent, and a front door symbol of the creativity and connection that the Rancho space hopes to inspire. Photo by Ryan Helean.