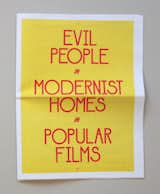

Evil People in Modern Homes

I was wandering around William Stout's architectural bookstore the other day when I came across Yale University graphic design student Benjamin Critton's wonderful tabloid treatise Evil People in Modern Homes in Popular Films. It's been noted many times that villains always wind up in cool modern homes in movies, but here's a sustained take on the phenomenon (in newsprint, no less) that spans the design and film canon from Diamonds are Forever to the Big Lebowski. I had a chat with Critton and here's what he had to say about his project.

Why did you elect to make a newspaper? Why not a magazine or a website, or even a video?

I've been experimenting a bit with small-scale publishing and audience-finding, and I wanted to see if taking the content from it's original medium would still make an engaging publication. And I suppose I'd like it to serve as a viewing list, of sorts—something that people might act on in order to see the entirety of the source material. I'd established a title that was sort of purposefully stupid in its candor—these three distinct subjects, the People, the Homes, the Films—and I wanted to have a system in which I selected just three stills from each film to coincide with the titling: one that shows the villain in question, one that shows the work of architecture, and one that shows the title card of the film. That was the intended formula from the beginning. When I realized that the representations of the films would be still images, I also realized they couldn't go directly into a Website or Motion piece, as people would expect to see the frames that preceded and followed each of the stills selected. Ultimately, it's a newspaper—as opposed to any other printed format—simply because the printing was cheaper and I could pick up the newspapers from a big web press down in Long Island City.

I love the variety of villains you've got from classic Bond movies to Twilight. How did you choose whom to include?

The paper went to press just this summer, about a month after I'd begun the research, and so the works included have simply to do with those I'd screened first. Hilariously, though, the trope is such that it's not restricted to just a single genre, which allows for a diversity of villain types.

Not to get too picky, but the vampires in the modern house in Twilight are good guys. They fight off the bad vampires and protect Bella, right?

You're right: the Cullens are essentially Good—not villains, per se. But I couldn't get over the fictional-historical precedence of the Vampire as a Bad Thing. Really, though, I included Twilight it because it was a more contemporary filmic and architectural reference point, and because the film has this priceless line, which I enlarged for the middle spread of the newspaper: Bella enters the Cullen's home, stops, gasps silently, and says "This is incredible; it's so light and open, you know?" And Edward responds: "What did you expect—coffins and dungeons and moats?" I needed to find a way to include Bella's recitation of that modernist truism.

A lot of the structures you've included--Lautners, Frank Lloyd Wright, Neutra--have such a California vibe. They seem to represent the sunny optimism of mid-century California, not the coldness that modernism is meant to suggest. Why omit the glass and steel castles of today (lame example but the rigid, hi-tech modern house devilish Anthony Hopkins lived in in Fractured), all technical precision and engineering triumph, from your list?

Fractured is a good reference; I'll add it to the list. The choice of films and the homes therein was due in part to the limitations I set up for the series, and in part to the default geography of filmmaking here in the States. I made it a rule that the residences had to be tangible, visitable places, which ruled out some of the more seemingly Cold residences that were fictional—studio-built set-pieces. And then, due to the fact that most of the films were shot in or around Los Angeles, the houses scouted on their behalf were often of some sort of indeterminate California aesthetic. It's funny, though—even within this conversation—that you bring up 'the coldness that modernism is meant to suggest.' I don't think that any iteration of modernism was ever intended to convey coldness, though it's certainly been codified that way in various pop cultural vehicles, Hollywood movies among them. I suppose it's funny, in the end, that even these happy, vibey California homes can somehow be retrofitted to house vice. And that the filmmakers would deem them appropriate containers for villainy in the first place is something I can't help but smile at.

Tell me more about the villains you have in the paper themselves. What makes Jackie Treehorn from the Big Lebowski like the Bond villains or Twilight's vampires or Rick Deckard in Blade Runner?

I don't really see them as all villains even. The Evil of the title is meant to suggest immorality in the broadest sense. That is, Nick Prenta is a racketeer; Ernst Blofeld, a supervillain; Rick Deckard (though in theory a protagonist), a drunk and a bounty hunter; Sam Bouchard, a murderer; Arjen Rudd, a [racist] drug-smuggler; Pierce Patchett, a pimp; Jackie Treehorn, a pornographer; and the Cullens, straight up vampires, every last one. So, the villains themselves are not alike—they're as varied as the houses they supposedly reside in; but they're linked by the fact that they are villainous, that they do morally questionable things, that they are essentially Bad.

What spurred you on to design this thing in the first place?

Last semester, in an architecture class with Kurt Forster, I was doing a bit of research into representations of modern[ist] architecture in cinema. It wasn't long before the trend became apparent. Spurred in part by Thom Andersen's 2003 documentary, Los Angeles Plays Itself—in which he talks of the city's inadvertent self-deprecation and the fact that they often poorly represent their vernacular architecture—I started a series of screenings of films that I thought could form the basis of a new canon. In publicizing the screenings, people suggested further examples, and I've been trying to grow the catalogue since. The creation of the newspaper was an effort to start a larger dialogue and to create a piece of printed matter that I myself would have liked to come across.