Western Promises

When discussing the magnitude of development in China, architect William McDonough is apt to point out: "One of the reasons you have to pay attention to China is that China will build new housing for 400 million people in the next 12 years. This is the equivalent of rehousing the entire United States in seven years."

That level of construction, McDonough warns, would result in huge losses of farmland and natural resources. So a few years ago, he and his partners proposed an alternative, which would be realized in Huangbaiyu, a little farming village in northeast China. Forty-two houses of a new model village were to be built in the middle of the old one, in what was to be the first phase of construction for the 400 sustainable homes that would house the entire community. The villagers’ old homes, which spread throughout the valley and nearby hills, would be turned into farmland, and the new houses would be powered by the sun and the fuel produced from organic waste. The new Huangbaiyu would embody McDonough’s cradle-to-cradle, rather than cradle-to-grave, principle of sustainability with the new village being essentially a proof of concept.

McDonough first told me about his grand designs for China in 2005. In the following two years, however, a trickle of reports from Huangbaiyu suggested that the project was not living up to its original promise. During the summer of 2007, I spent about five days in the village, reporting for Frontline/World. What I found was a cautionary tale not simply about the headlong rush to build in China, but about how sustainable development is as dependent on context and culture as on the concepts behind it.

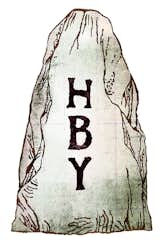

At the main entrance to the new Huangbaiyu—on what was previously cropland—stands a massive rock on which the village’s name is etched in red Chinese characters. The initials, in English letters, are carved vertically on the back:

Beyond the rock lie dirt roads and dozens of houses. In a region where people build their own homes and each looks different, McDonough’s plan consists of nearly identical single-family tract homes arranged in neat rows with modest yards. All but two are empty.

I talked with one of the people who lives in the new village. His name is Zhao Qinghao. The first thing I noticed about his home was that his entire walled yard had been turned into a garden. The corn was head-high, the tomatoes nearly ripe. In his kitchen, freshly picked cucumbers sat in a bucket of salt. Peas climbed up a trellis that curved over the short path from the front gate to his door. It looked like abundance, but it was merely enough— Zhao was only able to feed his wife and himself with these vegetables.

"The yard is too small," he explained. "It’s not suitable for farmers"—farmers like Zhao and the majority of the other 1,400 or so people in the village. He has the space to grow food for himself, but there’s no way he can make a living off of it.

Both Zhao and his neighbors live here because their old homes burned down in an electrical fire. Although the model houses cost more than most villagers can afford, local Communist Party officials struck a deal with Dai Xiaolong, the new village’s developer, enabling the two families to move in. Zhao, despite the house’s inadequacies, was grateful for the party’s assistance.

In the new houses, the ceilings are crisscrossed by a grid of cracks, and flakes of plaster peel off the surface. Shannon May, an anthropologist who has spent roughly a year and a half documenting the lives of the villagers for her doctoral thesis, blames Dai for the poor construction. An entrepreneur and the village head, Dai was tapped to develop the new Huangbaiyu even though, according to May, he was inexperienced.

Kent Snyder, a representative from the China-U.S. Center for Sustainable Development, also blamed Dai for the faulty construction, though the Center coordinated much of the project and was involved in choosing Huangbaiyu and Dai for this effort. Dai now claims that many of the problems with the houses have been fixed, though Snyder told me, "When Dai builds houses, people will move into them if they want to. If he doesn’t do a good job, then they’re not gonna move."

But for the villagers, and in the eyes of a close observer like May, there is a more fundamental problem. I saw it during my time there and it would have been obvious to anyone who spent any time with the people of Huangbaiyu.

Look at someone like Mr. Jiang, whose family lives beside a series of trout ponds. In pens on either side of his house are a pig, a couple of goats, and some calves, and on the other side of the ponds he keeps a few dairy cattle, whose milk is mixed with flour to feed the 20,000 fish he farms. Then there is the Yi family—three generations living under one roof—who showed me a yard full of ducks, chickens, pigs, and 63 cashmere goats. At the far southern end of the village, I scrambled up a steep ravine, following another farmer into the mulberry groves where he raises silkworms.

I also met Mr. Lu, a prosperous farmer who raises beef cattle, which he keeps just beyond his ponds. I asked him how Huangbaiyu had changed since his childhood, and he told me the greatest change was economic—that the villagers could now afford to build themselves sturdy homes that protected them from the elements. On the last day I visited him, a few men were busy pushing wheelbarrows and erecting a wood-framed addition to his house. Like most villagers, Lu has no plans to move into McDonough’s dwellings.

In Huangbaiyu, many farmers live near their fields or ponds, they keep their animals close, and, like the Yi family, they don’t always live in small units. The plans for the model village called for the opposite. Some farmers would have to move far from their land and ponds, and multigenerational families would have trouble fitting into the new houses. And although yards are not large enough to hold livestock, the houses do have garages, which might come in handy for those farmers whose plots are miles away. But only a handful of people in the entire village own cars, and one must question the sustainability of a village of commuters.

This cultural disconnect doomed the project from the outset. According to a document written by the China-U.S. Center for Sustainable Development before ground broke, "The yards may be too small to support the number of livestock that currently occupy many yards." But the report neither mentions this problem again nor suggests a solution. While those pushing and planning the project might have seen it as a great experiment in green design, what the villagers saw was unsuitable factory housing.

After returning from China, I attempted to interview McDonough, but my requests were turned down. His communications director told me to speak with Rick Schulberg, the director of the China-U.S. Center for Sustainable Development (where McDonough is a cochair), who also denied my requests. Snyder shifted blame to Dai, who he said had made the yards even smaller. Snyder didn’t even know about the garages. Throughout our interview he kept reciting the same simple refrain: "It’s not our village."

China is racking up new experiments in green living at quite a clip: the Linked Hybrid, Dongtan, the Qingdao EcoBlocks. Even McDonough lists designs for two large projects on his website, projects that, if built, would house hundreds of thousands of people. Huangbaiyu, meanwhile, is no longer featured in the architect’s online portfolio.

People planning these developments, and the others that will inevitably follow, would do well to consider Huangbaiyu. Dai once pointed out that the letters "HBY"—the characters etched on the rock at the entrance—also recall the initials of a well-known Chinese phrase: "hao bang yang." In English, that means "a good example."

Published

Last Updated

Get the Dwell Newsletter

Be the first to see our latest home tours, design news, and more.