Frank Lloyd Wright’s Unbuilt Predecessor to the Guggenheim Museum Comes to Life

In the fall of 1924, Frank Lloyd Wright was commissioned by Chicago businessman Gordon Strong to design a lavish tourist attraction atop Sugarloaf Mountain, Maryland. Following Strong’s instructions that the building primarily cater to the automobile, Wright conceived a striking "automobile objective" in the shape of circular ziggurat with spiraling ramps, panoramic views, and a dramatic planetarium at its heart.

When presented with the proposal in 1925, however, Strong coldly rejected Wright’s designs and not only wrote that the architect’s vision lacked "any relation to its surroundings" in his letters, but also insinuated that it was an unoriginal knockoff of the Tower of Babel.

Consequently, the grandiose design was never built and is counted among Wright’s approximately 660 unrealized drawings.

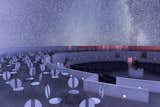

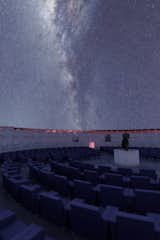

Yet, the project has been brought to life in another way—3D renderings. Under the direction of the Frank Lloyd Wright Foundation, Spanish architect David Romero transformed Wright’s designs of the automobile objective into photo-realistic images for the foundation’s latest issue of the Frank Lloyd Wright Quarterly magazine.

"Wright managed to combine in a single building the sense of something playful with the majesty of an impressive monument," Romero says. "It is a pity that it could not be built. If it had, I think it would be one of his most celebrated designs."

Designed to follow Strong’s instructions that the building "provide maximum facility for motor access to and into the structure itself," the massive structure would have been accessed via a car ramp that ascends clockwise—a descending counterclockwise ramp is placed beneath—and culminates in an open rooftop with sweeping summit views and gardens.

"The spiral is so natural and organic a form for whatever would ascend that I did not see why it should not be played upon and made equally available for descent at one and the same time," Wright wrote, adding that the ramps would allow "movement of people sitting comfortable in their own cars…with the landscape revolving around them, as exposed to view as though they were in an aeroplane."

Shop the Look

Although plans for the Sugarloaf Mountain automobile objective were ultimately dashed, Wright persisted in his interest with the spiral, which appeared in later projects from the Self-Service Garage and Point Park projects—both of which were completed in Pittsburgh in 1947—to the iconic Guggenheim Museum in New York City, where the spiral was dramatically inverted.

"The best way to understand Frank Lloyd Wright's principles of organic architecture is to visit his buildings and truly experience them," says Jeff Goodman, vice president of Communication & Partnerships at the Frank Lloyd Wright Foundation.

He continues, "When you sit in the furniture in the Garden Room at Taliesin West, you see how Wright frames views of the desert landscape to help you connect more deeply with the natural environment. All of the extant buildings are filled with lessons on how to live more beautiful lives, in harmony with the world around us. But, there are more principles to experience in Wright's unbuilt works, and while we will never have the opportunity to visit them in person, Romero's renderings help us to understand them on a much deeper level than ever before."

To see more renderings of unbuilt Frank Lloyd Wright projects, pick up a copy of The Frank Lloyd Wright Foundation’s magazine.

Published

Get the Pro Newsletter

What’s new in the design world? Stay up to date with our essential dispatches for design professionals.