This Housing Center Provides Sanctuary for Starting Over

There are two things that men leaving the prison system in New Orleans most commonly request from The First 72+, a nonprofit that helps the formerly incarcerated adjust to life on the outside. The first is enough privacy to wake up and not make eye contact with another man.

The second is a bubble bath.

New Orleans organizer and nonprofit cofounder Ben Smith devoted his life to helping men who were released from prison successfully reenter society. And now, a 3,200-square-foot transitional home designed by architecture firm OJT and named in his honor will continue his work.

Those are two things that "we made central to the design of the house," says Kelly Orians, who directs the Decarceration and Community Reentry Clinic at the University of Virginia’s law school and is a founder of The First 72+. In creating the Ben Smith Welcome Home Center, The First 72+ took its cues directly from the men it intended to serve. And, indeed, the home is equipped with full baths, complete with tubs.

Based on his previous experience as a resident, First 72+ reentry court case manager Troy Delone has an idea of the other comforts that future residents have to look forward to. "The bed, just in and of itself—having a soft mattress with those nice, solid clean sheets that were so comfortable," says Delone, who spent 16 years in the Louisiana State Penitentiary, the maximum security prison commonly known as Angola, named for the former plantation it occupies and Portuguese colony in Africa from which enslaved people who once worked there came. "It just gives you a peaceful vibe."

The living area provides space for First 72+’s executive director, Troy Glover, economic empowerment manager Meagan Jordan, and Delone to meet.

The project, a 3,200-square-foot house with the capacity to sleep eight, is the product of long conversations between designers and architects who sought to provide the ideal space for men leaving prison to make a fresh start. "[The design] mostly dealt with the way the organization worked with the residents and how the residents lived, both as a community and as individuals," says architect Jonathan Tate, who designed the space with his firm, OJT, as well as input from Orians and prison advocates. This meant delineating areas that provided both a sense of autonomy and connectivity, along with visitor access that didn’t interrupt residents, who have individual bunks, personal lockers, and access to laundry and bathrooms. "There were also regulatory operational issues that had to be considered in the makeup of spaces—no locks on lockers, etcetera," adds Tate.

"We want to be accessible to that jail. We want people to know that they can come here from right across the street."

—Kelly Orians, a founder of the First 72+ and director of the Decarceration and Community Reentry Clinic at the University of Virginia School of Law

A sharply angled roof provides an opportunity for spacious, expressive upstairs bedrooms and gives the structure a distinct look among other residences.

The First 72+ raised just over $500,000 in a five-year period from grassroots donations from a variety of sources, including the RosaMary Foundation, and a boost in visibility from the Greater New Orleans Foundation. The project’s largest contributor was IMPACT 100, an organization of 100 women who donate $1,000 each, then combine it in a single grant.

A central split divides the structure and the facade and features eight windows placed in a nonuniform configuration; both features are intended to emphasize the idea of separate units. The home’s jagged roofline stands out among the other residences in the area.

"We located all the bedrooms in the taller volumes of the building and wanted those spaces to be expressive—sharper, angled roofs—while the programming elements sloped away, which lowered the scale of the building to the street," says Tate.

While offering the creature comforts of home and more—including a spacious common area, a full-size kitchen with stainless-steel appliances, and a culinary classroom—the Ben Smith Welcome Home Center is designed to provide the residents with a stable, though temporary, readjustment period of 90 days.

If the goal was to create a space that felt nothing like the confined and often dehumanizing atmosphere of a prison, they succeeded. The interior is bright and airy. There’s a large common space for hanging out and a separate room for group meetings. The ceilings are high. The kitchen has stainless-steel appliances. In the back of the house, there’s a half bath next to a culinary classroom, another, wheelchair accessible bathroom down the hall in the residential area, plus two full bathrooms upstairs next to the bedrooms. Each bedroom sleeps two—but, crucially, provides privacy by placing cabinets for storage in the center of the room, between the two beds. The men can sleep, read, and relax outside of the line of sight of their bunkmate. Every aspect of the house is designed with intention, from the layout of the space to the splashes of color inside the drawers of the nightstands.

"We were trying to figure out how the furniture helped to really welcome people, how to create a warm, noninstitutional place," says Doug Harmon, founder and director of the Revival Workshop, which partnered with Tate on the layout, furniture, and selection of building materials. "If anyone deserves good design, it’s people in their situation."

To help execute the vision, members of the community The First 72+ serves had a hand in the project as well. Harmon’s Revival Workshop teaches woodworking to the formerly incarcerated; the participants built the closets. And volunteers from Angola’s hospice program stitched the colorful quilts that cover the full-size beds, which come with built-in headboards and reading lamps.

Each bedroom sleeps two and features built-in headboards with reading lamps, full-size beds, and storage cabinets that offer a bit of privacy. The house has full bathrooms to accommodate one of the residents’ main requests: a bathtub.

But even in a communal, transitional living space, the organization strove to create an environment that didn’t replicate incarceration. Though residents are meant to rotate in and out of the house—in a way not so dissimilar to the way people move through the prison system—the designers sought to make it feel like home. Doing that wasn’t always straightforward.

"Having the headboard and the nightstand integrated into a wall, there is a sense of being anchored," Harmon says. "You’re not in a bed that feels temporary. You’re in something that feels like it’s really substantial."

"You’re not in a bed that feels temporary. You’re in something that feels like it’s really substantial."

—Doug Harmon, founder and director of the Revival Workshop

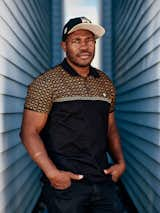

The Revival Workshop worked with the architects on the layout, furniture, and selection of building materials. Choices like walnut veneer plywood allowed the team to easily build and assemble durable pieces that evoke beauty and warmth. Doug Harmon (center), founder of the Revival Workshop, sits here with apprentices Jovan Butler (left) and James Washington.

Still, the housing is meant to be temporary. Each resident only stays in the house for 90 days, and that’s baked into the design, too. The First 72+ strove to create a space that was "comfortable, but not too comfortable," says Tate. "How do you make a space that feels special and their own and then have them move on?" Looking out through some of those windows, residents might see a somewhat unpleasant sight—their neighbor, New Orleans Central Lockup. But even that placement is deliberate. "We want to be accessible to that jail," Orians says. "We want people to know that they can come here from right across the street."

In an effort to foster a sense of accessibility, the transitional house sits just across from the city’s central lockup. The First 72+ office sits immediately next to the group home.

Staffers from the organization also assist residents with enrolling in social services programs that will help them get back on their feet. "They transitioned me back into society. They got me my license, my disability. They helped me get my Medicaid and Medicare—they got all my stuff straight before they let me go," says Raymond Girtley, a resident in the program. "They gave me the whole nine yards."

There are more subtle benefits to participating in the program, too. When Delone left The First 72+’s housing program, he was so focused on getting himself an apartment, he didn’t initially think to get furniture. "I learned from this place how to actually manage household stuff," he says.

Published

Last Updated

Topics

Where We Live NowGet the Dwell Newsletter

Be the first to see our latest home tours, design news, and more.