Design Icons: 24 Modern Architects and Designers That Have Shaped Our World

In our Design Icon series, Dwell takes a deep dive into one artist’s most popular—and most obscure—works. From modernist masters like Eero Saarinen to revered mainstays like Jean Prouvé, get to know your favorite designers a little better with these miniature history lessons.

Alvar Aalto

Finnlandia Hall is a centerpiece of the Finnish capital of Helsinki, boasting a towering auditorium and high roof, curving balconies, and an exterior of white marble and black granite.

A towering figure of Modernist architecture, Alvar Aalto began his career in the ‘20s in what was then the newly independent nation of Finland, helping define the style and aesthetic reputation of the rising Scandinavian nation. Aalto’s architectural creations, as well as his lighting, furniture, and glassware, were total works of art, often Expressionist in style, imbued with a keen awareness for those who would live and work inside.

Shigeru Ban

In 2013, Ban’s office introduced its new disaster housing prototype, the New Temporary House, whose exterior is made of insulated sandwich panels and fiber-reinforced plastic.

Since his beginnings in Tokyo in 1985, Shigeru Ban has been recognized for his insightful and innovative use of material, especially a focus on low-cost cardboard and paper for the construction of relief shelters around the world. One of Ban’s core insights—that architects don’t determine the permanence of a structure—rings especially true. While his body of work incorporates extraordinary modern art museums (Centre Pompidou-Metz) and fancy condominiums, the ease with which he creates fantastic, useful spaces for those most in need suggests an architect in touch with his audience.

Marcel Breuer

When this minimalist, L-shaped modern structure was first erected on the Massachusetts coastline, neighbors said it "looked like the ladies’ wing at Alcatraz," according to the original resident, John Hagerty. Decades later, guests are still stopping by to explore this inspired Walter Gropius/Marcel Breuer collaboration.

When designer and architect Marcel Breuer left Europe in the 1930s to teach architecture at Harvard and start his own practice, it served as a catalyst for the spread of Modernist design, a bend in the road as fortuitous and influential as the curved steel joints in his famous, tubular steel furniture. In the coming decades, his work with students and future luminaries such as Philip Johnson and Paul Randolph, as well as his own series of private residences and monumental public commissions, helped many appreciate and understand a new way of designing.

C. Howard Crane

Even if domes and arches were considered bad for acoustics, Crane made use of them in the hundreds, pushing the limits of aesthetics for the pure decadence of it. In its almost cathedral-esque proportions and ambiance, United Artists Theatre in Los Angeles, now the Ace Hotel, is a luxurious example.

Self-made visionary C. Howard Crane moved to Detroit in the early part of the 20th century with a lot of energy and grand plan: to follow lucrative automobile money and get it to shake hands with the emerging moving pictures boom, via the most spectacular buildings ever seen in Michigan. In the spirit of innovation, Crane set up office without any formal architecture training, building instead with what he called "instinct." Stylistically, his instinct told him that if the moment was the roaring, post-war ’20s, a time when money was burning through wallets, it was a time to seek the new and the indulgent. Architecturally, he said, "there should be no specialists in the practice of architecture—achieving success with experience of designing and erecting buildings for a particular purpose will create aptitude and ability in that field." By the time of the stock market crash of 1929, Crane’s firm had designed more than 300 theaters in America, Canada, and Britain, with over 50 in the city of Detroit alone.

Buckminster Fuller

"I seem to be a verb," he once said. Even more than 30 years after his passing, when the magnificent machine that was Buckminster Fuller’s mind stopped minting ideas and inventions at a prodigious rate, there's still a sense that he is always in motion, moving too fast for the rest of us. You can call Richard Buckminster Fuller many things: a prophet of environmentalism and the counter-culture, decades ahead of the fringe; a Doc Brown of design thinking, whose buoyant optimism held firm to the idea humanity can innovate out of its problems; or simply a self-made genius. But most just called the inspirational thinker "Bucky."

Frank Gehry

For the Richard B. Fisher Center in Annandale-on-Hudson, New York, Gehry worked in collaboration with acoustician Yasuhisa Toyota and a team of theater consultants. "The front façade of the building can be interpreted as a theatrical mask that covers the raw face of the performance space. Its abstract forms prepare the visitor to be receptive to experiencing the performances that occur within," Gehry said of his design.

Frank Gehry’s recognizable designs are often cited as being among the most important works of contemporary architecture. Born in Toronto, Canada, Gehry was a creative child. Encouraged by his grandmother, he would build little cities out of scraps of wood from her husband's hardware store. His buildings consist of juxtaposed collages of spaces and materials that make people appreciate both the theater and backstage simultaneously. A winner of the Pritzker Architecture Prize, Gehry was commended by the jury as, "always open to experimentation. He has as well a sureness and maturity that resists, in the same way that Picasso did, being bound either by critical acceptance or his successes."

Eileen Gray

The E 1027 Adjustable Table: one of many Eileen Gray pieces that are manufactured by Aram Designs Limited.

Modernist design is not often associated with opulence and luxury, but Eileen Grey, an Irish lacquer artist, interior designer, and architect, combined the lavishness of art deco design with the geometric forms of the International style, creating an aesthetic of her own. Through her celebrated lacquered folding screens, expanding side tables, industrial lamps, and modernist architecture, Gray integrated stark forms and geometric decorations with luxurious materials and traditional techniques, constructing dark, sensual objects and interiors that communicated a distinctly unique modernity.

Walter Gropius

While the first home Walter Gropius constructed in the United States was his own home in Lincoln, Massachusetts, his first official commission was the Hagerty House in Cohasset, Massachusetts.

Best-known as the founder of the German art school Staatliches Bauhaus, where he served as director for many years, Gropius also founded the Architect's Collaborative (TAC) in 1945, and designed the D51 armchair and the F51 armchair and sofa. Beyond his pioneering work as an architect, instructor, and designer, Gropius was a theorist and a visionary. In his 1923 essay, "The Theory and Organization of the Bauhaus," Gropius outlined the governing philosophy of the Staatliches Bauhaus and posed critical, forward-thinking questions that echo visibly through all the subsequent ages of modern design. "But what is space," he asks. "How can it be understood and given a form?"

Greta Grossman

Today, the Grasshopper lamp is undoubtedly Greta Grossman's most famous design. Introduced in 1947, the Grasshopper is both sophisticated and unobtrusive, which allows it to work well on its own and when paired with other designs.

Today mostly remembered for her elegant and playful Grasshopper Lamp, in the 1950s and '60s, Greta Grossman was a highly sought-after architect, interior, and industrial designer who worked across two continents. Growing up in Sweden in 1920s, Grossman, as a precocious teen, defied expectations by taking up woodworking, a predominantly male profession at the time. She followed this venture by becoming one of the first women to graduate from the Stockholm School of Industrial Design. Greatly influenced by functionalism, Grossman travelled across Europe, visiting the pioneering Weissenhof settlement and joining the conversations at the Motta restaurant in Milan, a primary meeting place for Milan’s art and design world, where, among others, she befriended the famed designer Gio Ponti.

Zaha Hadid

Zaha Hadid Architects was appointed as design architects of the Heydar Aliyev Center following a competition in 2007. The center, designed to become the primary building for Azerbaijan's cultural programs, breaks from the rigid and often monumental Soviet architecture that's so prevalent in Baku, aspiring instead to express the sensibilities of Azeri culture and the optimism of a nation that looks to the future.

When Zaha Hadid passed away in March 2016, she left the world of architecture with an irreplaceable legacy. As the first woman to receive the Pritzker Architecture Prize (2004), she was described by The Guardian of London as the "queen of the curve" who "liberated architectural geometry, giving it a whole new expressive identity." Hadid received the United Kingdom's most prestigious architectural award, the Stirling Prize, in 2010 and 2011. In 2012, she was made a Dame by Queen Elizabeth II for services to architecture, and in 2015, she became the first woman to be awarded the Royal Gold Medal from the Royal Institute of British Architects. Some of her designs have been presented posthumously, including the statuette for the 2017 Brit Awards—and many of her buildings are still under construction, including the Al Wakrah Stadium in Doha, a venue for the 2022 FIFA World Cup.

Hans Hollein

A brilliant green granite and glass creation that had an abrupt debut, considering its location in the city’s St. Stephens Square, the Hass House actually had a historic pedigree (the outside mirrors the corner of an old Roman fortification). While Hollein was initially criticized—"I get anonymous letters saying I should jump off the top of the Haas Haus," he said in an interview—the building has since been recognized for introducing a modern aesthetic to Vienna's downtown.

Multidisciplinary is a tag thrown around quite often in the design and architecture world, but for Hans Hollein, a restless thinker and theorist, the concept was second nature. "Everything is architecture," said the architect, professor, writer, and designer, whose work, especially with museums, earned him a Pritzker Prize in 1985. Hollein made a formative trip across the U.S. in the ‘50s and ‘60s, studying at Illinois Institute of Technology in Chicago and the University of California, Berkeley, and meeting architects he admired, such as Mies van der Rohe and Philip Johnson. But as the obscure nature of a road trip to see all seven towns named Vienna in the United States suggests, his heart was in Austria, the city where he practiced, and—over decades of creation and construction—helped shape the cultural landscape.

Philip Johnson

Built in 1953, the Wiley House is made up of a single glass-and-wood rectangular pavilion that’s perched on top of a rectangular box made of stone and concrete. Johnson chose the six-acre plot of land himself and was particularly fond of the natural slopes of the site, which is surrounded by hickory trees.

It's safe to say that Philip Johnson was one of the most famous and influential American architects of the 20th century. A pioneer of American modernism, Johnson designed the iconic Glass House for himself in 1949—creating a distinctive glass facade that was inspired by Mies van der Rohe's Farnsworth House. Although the Glass House is undeniably his most famous residential property, a look through these other significant residential projects might leave you struggling to choose a favorite.

Louis Kahn

Louis Kahn opened up the interior of this brick library at Phillips Exeter Academy with a ceiling clerestory, which allowed sunlight to flow in and colorfully contrast with the stone-and-wood interior. Illumination was a focus down to the smallest detail, such as the teak study corrals positioned in light-filled spots.

A master of turning simple forms and classic motifs into extraordinary monuments, American architect and professor Louis Kahn created a spartan body of work that’s become hallowed ground for his peers, influencing a generation. "It is important that you honor the material," the perfectionist would tell his students, and for Kahn, that meant sculpting gorgeous curves and blocks of concrete and brick, massive structures large enough to inspire awe but still deft enough to play with light. His work was inspired by a visit to Roman ruins when he was in his 50s, and still achieves the soaring, spatial poetry of his peers without the advantage of more lightweight material.

Le Corbusier

Located outside of Paris in Poissy, Villa Savoye is the best illustration of Le Corbusier's five points of architecture. A modern take on a French country house, the home is still considered to be one of the most significant contributions to modern architecture in the 20th century.

In 1923 when Le Corbusier published his tome "Vers une Architecture" (Toward a New Architecture), the Swiss-French architect declared, "A house is a machine for living in." He elaborated—that by living in efficient houses, we can be both more productive and more comfortable, stating that good engineering can achieve harmony and beauty. One look through this pioneer's modernist architectural works will prove just that.

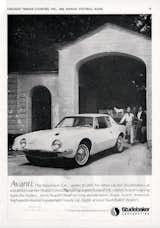

Raymond Loewy

Italian for forward, the Avanti was created by Raymond Loewy and a team of designers during a 40-day crash course at the behest of Studebaker President Sherwood Egbert. Sporting a sleek look during a period of automotive overindulgence, the Avanti also boasted numerous safety features ahead of its time.

In 1951, industrial designer Raymond Loewy was so prolific, and so highly regarded by the captains of industry, that this humblebrag could go unchallenged: "The average person, leading a normal life, whether in the country, a village, a city, or a metropolis, is bound to be in daily contact with some of the things, services, or structures in which R.L.A [Raymond Loewy Associates] was a party during the design or planning stage." Considering the then-boom in post-war consumer products, Loewy’s streamlined saturation of the American experience becomes all the more impressive. While industrial design icons such as Jonathan Ive or Phillipe Starck revolutionized a product category, or put their stamp on numerous industries, Loewy’s mark on everyday experiences across the spectrum of design has rarely been duplicated.

Ludwig Mies van der Rohe

One of the most significant of Mies' works, the Farnsworth House in Plano, Illinois, was built between 1945 and 1951 for Dr. Edith Farnsworth as a weekend retreat. The home embraces his concept of a strong connection between structure and nature, and may be the fullest expression of his modernist ideals.

Ludwig Mies van der Rohe's International Style was the impetus for the midcentury modernism we know today. With his glass-and-metal creations and his iconic Barcelona chair, Mies sought to establish a new architectural ethos that would represent modern times. His work was the cornerstone for the Museum of Modern Art's 1932 exhibition The International Style (curated by Philip Johnson and Henry-Russell Hitchcock), which brought the modernist movement to a wider audience and solidified his role as a leader. His legacy lives on through his influential ideology, which proves that—as the architect once stated—"less is more."

Jasper Morrison

A striking example of Jasper Morrison’s philosophy that there aren’t necessarily new forms, just new ways to combine and recontextualize what's come before, Flower Pot Table was assembled in an almost ready-made fashion.

Jasper Morrison once spent four years designing a fork. While there’s plenty of personality traits you could assign to someone who spent the equivalent of a presidential administration obsessing over cutlery, sensitive may be the most fitting for the London–based designer. Since gaining notice alongside a generation of new British designers in the late ‘80s, Morrison has excelled at form and function without unnecessary flair. "Atmosphere" is a word he often uses to describe his work, and as the title of his 2005 exhibit with Naoto Fukasawa, "Super Normal," suggests, he strives for designs that don’t overturn conventional wisdom as much as evolve, taking a classic role and improving upon the delivery. Design should always be better than what came before, he says.

George Nakashima

Conoid Bench is an intricate example of George Nakashima placing minimal adornments on the wood, merely capturing it, preserving it and giving it a second life.

Working with a reverence for his material that bordered on spiritual, woodworker and designer George Nakashima (1915-1990) created one of the more influential legacies in furniture in the 20th century. Cutting wood was like cutting diamonds, he once said, a philosophy reflected in his body of work, filled with intricate pieces that preserved and magnified the beauty of every knot and grain. He would often keep boards around his workshop in Bucks County, Pennsylvania, for years before they would reveal themselves to him.

Oscar Niemeyer

The tomb of President Juscelino Kubitschek, designed by Oscar Niemeyer, provided the late leader with a fitting resting place in the modern city that he helped create. A statue of the founder rests atop a large, question-mark shaped sculpture.

Brazil’s modern architectural visionary Oscar Niemeyer (1907-2012) imagined buildings as sensuous and curvaceous as the beauties he’d see strolling the Copacabana beach, within eyesight of his main studio in Rio. He said "form follows feminine," but music is almost a more potent metaphor for his work with concrete: it was said that the songs of bossa nova legend Tom Jobim were like a house built by Niemeyer. He was considered the last of Modernism's "true believers," with a career that spanned decades and continued until the very end of his 104-year-long life.

Jean Nouvel

As with many of Jean Nouvel's designs, Cyprus Tower, a high-rise building located in the center of Nicosia, is ready-made with sprouts of greenery. Landscaping covers 80 percent of the building's southern facade.

French Pritzker Prize-winning architect Jean Nouvel is credited by the New York Times in a profile piece as "exceptionally good at allowing a building to take on a personality of its own." Sometimes controversially received, Nouvel's intentions with his buildings—in his own words—is to access "...the poétique of the situation. I am a hedonist, and I want to give pleasure to other people." Here is a sample of some of the 71-year-old architect's most influential designs throughout his illustrious career.

Charlotte Perriand

Charlotte Perriand’s first landmark collaboration with Corbusier and Pierre Jeanneret, this triptych of chromium-plated steel chairs, presented a Modernist view of living. Each was crafted with a specific function: the B301 sling back chair was for conversation, the LC2 Grand Confort was for relaxation, and the B306 chaise lounge was meant for sleeping.

Many innovators helped usher in the Modernist movement, but French architect, furniture maker, and interior designer Charlotte Perriand turned lofty ideals into revolutionary living spaces. Her extended collaboration with Le Corbusier made the sleek, chrome-finished future a reality, but her continued evolution and experimentation with different forms and materials made her a true icon. In a career filled with impressive collaborations and an extended and influential stay in Japan during WWII, Perriand went on to create a wealth of influential furniture pieces—including chaise lounges, armchairs, and tubular "equipment for living"—as well as scores of influential interiors, including a conference room for the United Nations in Geneva, the Unite d'Habitation housing project in Marseilles, and the Méribel ski resort.

Jean Prouvé

The French metalworker, furniture designer, and architect helped revolutionize the use of steel in architecture and prefab housing. Perhaps his most iconic piece of furniture, the Standard, is anything but—a delicate fusion of engineering and design skill. The curved steel legs, larger in the back due to Prouvé’s observation that the rear supports the brunt of a person’s weight, contrast well with two simple pieces of bent oak.

During a time when his contemporaries were being recognized as icons, French metalworker Jean Prouvé would rather have been addressed as an engineer or factory worker. This modesty, and a fidelity to material and craftsmanship, may have been what allowed him to help revolutionize the use of steel in design and construction. Folding metal like some fold paper, Prouvé and his forward-thinking work effectively fed the 20th century’s obsessions with steel and prefab construction.

Eero Saarinen

Dubbed the "Grand Central of the Jet Age" by critic Robert A.M. Stern, Eero Saarinen’s curvaceous TWA Flight Center was a paean to the romance of flight. The sloped concrete roof recalls two flapping wings, while contours constantly bend and flow into each, creating a fluid collection of terminals, staircases and forms. After being shuttered for years, the space has been turned into a luxury hotel.

Bold curves, colorful accents and technical vision: Finnish-American architect Eero Saarinen’s body of work represents Modernism’s playful side in bloom. His iconic buildings, from the Gateway Arch to the Miller House, helped symbolize America’s buoyant post-Cold War period, and often looked as streamlined and glamorous as the jets taxiing in front of one of his greatest creations, D.C.’s Dulles International Airport.

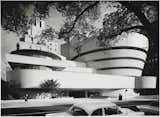

Frank Lloyd Wright

Wright’s last major work—and one of his most iconic—sadly didn’t open until six months after the architect’s death. Nevertheless, the Guggenheim Museum is one of the most important pieces of American architecture and is considered to be Wright’s most important contribution.

The leader of the Prairie School movement of architecture, Wright was an American architect who designed structures that were in harmony with their environment—a philosophy he called organic architecture. We’ve rounded up ten of Frank Lloyd Wright’s modernist structures that we love—all of which seem just as contemporary today as they did when they were originally built.

Related Reading: 10 Classic Midcentury Pieces That Will Never Go Out of Style

Published

Get the Dwell Newsletter

Be the first to see our latest home tours, design news, and more.