Dwell Reflects on Frank Lloyd Wright in Honor of the 150th Anniversary of His Birth

The beloved architect's work is just as relevant today as when it was created—and it continues to influence design in various ways. So, the 150th anniversary of his birth is just one more reason to celebrate him. Here, we reflect on all the times we've embraced the American master's work over the years.

10 Frank Lloyd Wright Buildings We Love

"The good building is not one that hurts the landscape, but one which makes the landscape more beautiful than it was before the building was built." -Frank Lloyd Wright

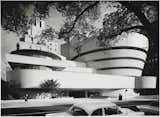

With so many masterpieces under his belt, it's subjective as to which one is the most iconic or groundbreaking. But one thing for certain is that the Guggenheim Museum is one of the frontrunners. As his last major work in his life—which sadly wasn't completed until after his death—this cultural institution in New York City will always be one of the most important pieces of American architecture, and is considered by some to be Wright's most important contribution.

Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, designed by Frank Lloyd Wright, photographed in 1959. Gelatin silver print.

The Hollyhock House in Los Angeles

Recently re-opened to the public, the story behind The Hollyhock House is filled with all the drama of a Hollywood film. As Wright’s first project in Los Angeles, it was filled with challenges from beginning to end. Commissioned by Aline Barnsdall, a wealthy oil heiress and arts patron, the iconic Hollyhock House was built between 1919 and 1921. After hiring Wright to create a "theater campus" where she would live with her young daughter, Barnsdall abruptly fired Wright in 1921 in the middle of construction, after financial disagreements and personality differences between the two bubbled to the brim.

She went on to hire Rudolph Schindler, the Austrian-born architect who was the project manager on the Hollyhock House, as well as a close friend to Wright. Schindler—who had also been making waves in the modern architecture world at the time—left his own mark on the design, along with some characteristic details that came from the participation of Richard Neutra, another iconic Viennese-born architect who was also involved.

Wright took inspiration from pre-Columbian temple forms, and many people have referred to it as one of Wright’s first "Second Period" designs, following many years of him working within his signature "Prairie Style." It was never actually lived in by anyone, but is now open to the public for tours.

In an attempt to create a strong connection to nature, Wright incorporated outdoor sleeping porches onto all five of the bays. This was an experimental and forward-thinking practice that both Richard Neutra and Rudolph Schindler also incorporated into their Los Angeles designs.

Wright-Designed Prefabs

As Wright's first attempt at attainable architecture, his American System-Built Homes were crafted between 1915 and 1917 with pre-cut factory lumber to save cash and labor. They included half-dozen duplexes and bungalows on the 2700 block of West Burnham Street in Milwaukee.

The Erdman homes were a series of three prefabricated structures that Wright designed for Marshall Erdman, a builder who had collaborated with Wright on the Unitarian Meeting House in Madison, Wisconsin. Each "set" would come with all the major pieces needed to assemble a home, while the buyer would have to provide the foundation, wiring, and plumbing. They would even have to submit a topographic map for Wright’s approval.

The Rudin House in Madison—built following Lloyd Wright's prefabricated Plan #2 for Marshall Erdman's company—is one of two homes built as a large, flat-roofed square with a double-height living room accented with a wall of windows.

Ken and Phyllis Laurent House

The Ken and Phyllis Laurent House that Wright designed for a couple in Rockford, Illinois, has opened to the public after an exhaustive preservation and restoration effort. It's the only handicap-accessible building in the celebrated architect’s portfolio.

After a botched operation left Ken Laurent paralyzed from the waist down, he reached out to Wright in August 1948 with a preliminary budget and a description of his lot. He included the following note: "To give you an idea of my situation, I must first tell you that I am a paraplegic. In other words, due to a spinal-cord injury, I am paralyzed from the waist down and by virtue of my condition, I am confined to a wheelchair. This explains my need for a home as practical and sensible as your style of architecture denotes." Wright did not disappoint.

The house is one of about 60 so-called Usonian houses that Wright designed for middle-income clients starting in 1936.

The Canadian Banff Pavilion

Wright designed only two structures in Canada. One of them was a pavilion in Banff, Alberta, in 1938, following significant damage from flooding. Created as a visitor center, the structure supposedly wasn't what Banff's residents had requested, which was a sporting facility with curling and hockey rinks. It also was said to have not stood up well to the harsh Canadian winter. However, it eventually became popular, and its demolition was met with protest. The architectural community and Frank Lloyd Wright enthusiasts have lamented the destruction of the pavilion, which featured a single long room with overlapping eaves and a low-hipped roof. It was an example of Wright's "Prairie School Style," known for its horizontal lines that reference the prairie landscape. The Frank Lloyd Wright Revival Initiative, which works to bring demolished or never-realized Wright structures back to life, has spearheaded an effort to rebuild the pavilion.

10 UNESCO World Heritage Nominations in 2016

In 2016, 10 of Wright’s buildings were nominated to become UNESCO World Heritage sites. The nominees included Fallingwater, the Hollyhock House, Taliesin West, Taliesin East, Unity Temple, the Guggenheim, Price Tower, Marin County Civic Center, the Frederick C. Robie House, and the Herbert and Katherine Jacobs First House. While the buildings had previously been submitted and had made the tentative list, they were ultimately passed over by the World Heritage Committee, disappointing Wright fans worldwide.

Working With the Same Photographer His Whole Career

In 1939, Frank Lloyd Wright hired 22-year-old Pedro Guerrero to be Taliesin West’s resident photographer, which kicked off the start of a collaborative bond that would last until Wright’s death in 1959. Guerrero passed away in 2012, but an exhibit celebrating the 100th year of his birth, in addition to Wright's 150th, is on view at Taliesin in Spring Green, Wisconsin, through October.

"When I set up this shot of Wright in his studio at Taliesin, he hadn’t shaved that morning and told me he wasn’t about to. So I had to move the camera back to conceal the stubble, which actually improved the shot." Behind Wright is a model of the San Francisco Call building, a favorite of his that was never built.

Gas Station For a Usonian Suburban Vision

Built in 1958 and designed by Wright himself, the R. W. Lindholm Service Station is located at 202 Cloquet Avenue in Cloquet, Minnesota, and is still in use today. It's one of the few designs from Wright's utopian plans for Broadacre City that was actually implemented. The building features a cantilevered copper canopy and is primarily made of concrete, glass, and steel. There's a glass observation lounge on the second floor for community interaction. Cypress, one of Wright's favorite materials, is used throughout the interior.

Two FLW Homes For Sale

Located on 3.77 acres in Minnesota’s Lake Forest neighborhood is a 2,647-square-foot, three-bedroom home that was designed by Wright in the late-1950s. When Paul and Helen Olfelt commissioned Wright to design a home for their family in 1957, he worked on the project until he passed away in 1959.

Now in their 90s, the Olfelts are asking $1,295,000 and have it listed for sale by BERG LARSEN GROUP of Coldwell Banker Burnet.

Though this home is close to downtown Minneapolis, it sits on a quiet, 3.77-acre piece of land. When you approach the brick home, it immediately becomes clear that it’s a Frank Lloyd Wright-designed home—thanks to its wing-like shape and Cherokee Red-painted steps.

Built in 1955, Wright’s last extensive residential commission is on the market for $7,200,000. Located in New Canaan, Connecticut, on a 15-acre piece of wooded land that looks over the Noroton River, 432 Frogtown Road was first built for Joyce and John Rayward and has only been in the hands of two other owners. Also known as the "Rayward-Shepherd House" or "Tirranna," Wright designed this spectacular home during the last years of his life while he was completing the Guggenheim Museum in New York City. The home is listed here through Houlihan Lawrence.

Published

Topics

Frank Lloyd WrightGet the Pro Newsletter

What’s new in the design world? Stay up to date with our essential dispatches for design professionals.