Surrealist Jewelry, Inventive Ceramics, and a Giant Wooden Cigarette Bring Whimsy to the Winter Show

The Winter Show, now in its 71st year, is one of the antique and fine art world’s most venerable events—a 10-day extravaganza of curiosities, valuables, collectibles, and artwork, housed in the cavernous Park Avenue Armory. The objects on display are often the sort you’d see in a museum, in a vitrine in a gallery attended to by security—but they’re almost all for sale. (And, if you ask politely, you can touch them.) This event is one of the oldest antique fairs in the United States. It’s a charitable endeavor, an annual benefit for the East Side House Settlement, which provides critical community, educational, and workforce-related services for residents of the Bronx and the northern reaches of Manhattan.

There’s truly a treasure around every corner, if you’re a serious collector, a museum curator, or just a lookie-loo with an appreciation for the finer things of the past. The range is vast. For example, a booth full of ancient armor and antiquities neighbors a booth with delicate faience German chinoiserie and a soup tureen shaped like a parrot. Unsurprisingly, my eye at the fair was trained to seek out the surreal and the whimsical—an appropriate response to and balm for the various existential and actual horrors of the world that are starting to hit a little too close to home right now.

Here's what stood out at this year's fair.

Galerie Gmurzynka

Tom Wesselman’s giant cigarette was by far the most alluring thing I saw—five feet long and made of painted wood with a thick plume of smoke that, from almost every angle, looked dynamic and unabashedly sexy. Smoking is bad (they say), but a lit cigarette sculpture from an American Pop artist feels fresh in the way a Warhol I passed on my stroll could never.

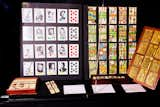

On the left, a set of playing cards designed by French artist Yannick Pennanguer in 1989 features images of musicians like Thelonius Monk and Billie Holiday. On the right, a set of 19-century French playing cards that are actually tiles sit next to the brass plates for a set of playing cards designed in 1915 by Armand-Gustave Houbigant, the son of a royal perfumer.

One of the fair’s more showstopping moments was at Daniel Crouch, a rare books dealer based in London. They brought just a smidgeon of artist Jean Vareme’s personal collection of playing cards and other associated ephemera–touted as the largest collection in private hands. (Should you feel moved to purchase the whole lot, Crouch is selling the entire collection for a cool seven figures.)

Also at Daniel Crouch was the second best thing I saw at the fair. When Nixon launched his war on drugs, a group of stoners in Berkeley responded by making a board game called "Scam: The Game of International Drug Smuggling"— an incredible artifact of our recent past that plots out a path from dropout to kingpin, by way of Afghanistan, Mexico, or South America. The goal of the game is to make a million dollars by selling the drug of your choice, without getting caught.

Amongst the sea of Tiffany glass on display at Macklowe Gallery’s booth, the Prism lamp stood out in part because it looks nothing like what you think of when you think of Louis Comfort Tiffany.

Here's the Prism lamp up close! She’s a saucy little thing, prim but fun, and as Ben Macklowe pointed out to me, a unique representation of how Tiffany was influenced by imperialism, exoticism, and more than a touch of Orientalism, reflected in the Moroccan-inspired metalwork on the shade. It’s the kind of lamp that is more sculpture than function, and also, timeless in the sense that you could plop it in any space from a concrete bunker to your grandmother’s lace-curtain parlor, and it wouldn’t look out of place.

Truthfully, if I could’ve lifted everything from this booth into a waiting U-Haul idling on Park Avenue, I would have. That’s just a kind way of saying that the collected objects and works at Maison Gerard were all so beautiful and interesting that it was hard to choose a favorite.

A valet is a very old-timey piece of furniture that I think is still extraordinarily useful—and made even more so with the addition of a seat, like this contemporary interpretation, essentially a hybrid, from French artist Aline Hazarian. It’s a little fussy and very pretty—two wonderful qualities in chairs and furniture in general.

A trio of Murano caged glass pendants strung from the ceiling adds a little bit of drama and a sense of playfulness to the space. (The white cloth covers on the chains that hold the lamps aloft dress up the lamps in a way that feels intentional not just for function but for looks, too. Lighting should wear outfits, when and if the occasion calls for it.) While I could see these pendants fitting in wherever you want to put them, the bubbly glass looks chic when dangled over "L’aurore (The Dawn)", a marble sculpture by Paul Rocheil, created sometime in the 1930s in France.

This Bugatti throne chair, designed by Carlo Bugatti of the automotive company Bugatti, is a glorious example of the Moorish influence in design—popularized by one Lord Battersea, who had Bugatti design his bedroom in Surrey in the early 1900s. (Fun fact: a Bugatti throne chair was featured in the opening scenes of Alien: Covenant).

It’s perhaps rude to compare this delightful wooden dog, carved from a single hunk of linden wood, to a chainsaw-carved bear you might find in front of a cabin in Tahoe, but they do share an aesthetic DNA. This iteration, a German poodle, has intricately whorled fur, all hand-carved, and would be a bit of fun anywhere it lands.

As Didier reiterated to me over the course of our conversation, jewelry is really an intimate expression of affection—literal tokens created by artists as one-offs, a gift for a lover that is far more personal than a painting ever could be. This gold vermeil cast is of the model Veruschka’s mouth, created artist Claude Lalanne, and originally made along with a cast of the model’s midriff and breasts for Yves St. Laurent and made famous by a 1969 Vogue spread shot by Irving Penn.

Joan Mirviss’s quiet booth contained a vast number of contemporary woman-made Japanese ceramics, all of which expanded my personal understanding of the capabilities of clay. Tomita Mikiko’s "Stupa For Life" is an impressive and towering sculpture inspired in part by her childhood in Portugal. Viewed at a distance, it looks vaguely organic and a little aquatic—a decorative object for a sea witch’s foyer, perhaps.

I’ve saved the most breathtaking for last—a sculpture by Tanaka Yū, that closely resembles fabric and demonstrates the versatility and lightness of clay in a way that I’ve never seen before. It’s a clever little optical illusion that makes you want to touch the art. (I wouldn’t recommend that here.)

Published

Topics

Design NewsGet the Pro Newsletter

What’s new in the design world? Stay up to date with our essential dispatches for design professionals.