The Surprising Sources of Space-Saving Inventions

Welcome to Origin Story, a series that chronicles the lesser-known histories of designs that have shaped how we live.

Long before the Covid pandemic had people reconfiguring their homes to fit multiple—and sometimes competing—functions (think: dining rooms with on-demand desk setups, ad hoc gyms in unused bedroom corners), people were devising furniture and home wares that did more with less. Some of today’s most ubiquitous small-space inventions were born from the minds of makers who sought to solve particular problems in their own compact offices or residences. Others have more unconventional backstories, stemming from unrelated scientific missions before making their way into our homes. Read on for some of those tales.

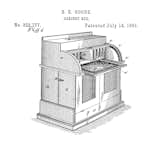

The Folding Cabinet Bed

In the late 19th century, inventor Sarah E. Goode’s novel solution to the urbanite challenge of saving space in small apartments made her one of the first African American women to receive a United States patent. Born into slavery in Toledo, Ohio, in the mid-19th century, she gained her freedom after the Civil War and moved to Chicago, where she met her husband, Archibald, a carpenter with whom she opened a furniture shop. During that time, Goode designed the cabinet bed, which could be folded together to "occupy less space," she wrote in her patent application, and "form a desk suitable for office or general use." In 1884, Goode exhibited her flexible furniture creation at the Illinois State Fair. The following year her patent was granted.

The Murphy Bed

Goode’s design and an 1899 folding bed by African American inventor Leonard C. Bailey were precursors to the widely known variation named after inventor William Lawrence Murphy. At the turn of the 20th century, Murphy designed a bed with a pivot system that allowed it to fold up neatly to the wall behind it while he was living in a San Francisco studio apartment. As the lore goes, saving space wasn’t his only motivation: Norms of the time made it uncouth for a woman to enter a man’s bedroom, so in order for Murphy to host his love interest without risking scandal, he had to be able to stow away the bed to turn the space into a parlor. His "Disappearing Bed" was patented in 1912, the same year he married said love interest. By the mid-1920s, Murphy beds were considered status symbols, touted as luxury features in hotels and apartments. The fold-down bed was also a pop culture fixture, most famously appearing as a slapstick prop in a 1916 Charlie Chaplin film.

The Clothes Hanger

Some historians credit the first clothes-hanger-type object to Thomas Jefferson, who is said to have devised a clothes-hanging contraption for a closet at Monticello. But what’s widely recognized as the earliest inspiration for the modern hanger was a rounded wire coat hook invented by O. A. North in 1869, which was improved upon by Albert J. Parkhouse in the early 1900s. Parkhouse, an employee of a Michigan wire company, showed up at work one morning to find all the coat hooks occupied, so he fashioned a wire hanger with a bent hook at the top that could be hung from a rod, allowing more coats to be stored at once.

The Dustbuster

If NASA was going to spend the money to send a man to the moon in the late 1960s, it wanted the Apollo astronauts to bring a bit of the moon home with them. Spacecraft, though, are not known for their capaciousness, so the agency gave American tool manufacturer Black+Decker a mission: to design a lightweight, cordless drill small enough for the astronauts to bring with them in the vehicle and powerful enough to extract lunar samples from as much as 10 feet below the surface. What the company came up with worked and led it to develop a 14-inch, handheld vacuum cleaner using refined technology from the moon drill. In 1979, Black+Decker introduced the Dustbuster, which the following year became the company’s first ever design patent—and inspired it to create its now-robust household products division.

Top photo by Keystone-France/Gamma-Keystone via Getty Images

Published

Get the Dwell Newsletter

Be the first to see our latest home tours, design news, and more.