From the Archive: How the Interstate Shaped the Tri-State Area

As a part of our 25th-anniversary celebration, we’re republishing formative magazine stories from before our website launched. This story previously appeared in Dwell’s September 2006 issue.

What does the interstate have to do with your house or apartment and the food in your fridge? What does the widened state highway down the block have to do with the shape of your town or city? What does the automobile have to do with where kids hang out on the weekend? Why are bus routes a reflection of the quality of social justice? It is these and other questions I have been thinking about while traveling the country for the past few months, checking out cities and towns and seeing how people get around. And I don’t want to get ahead of myself, but you should know right off that even though the word "transportation" might make your head fall toward to the pillow or make you roll your tired-from-commuting eyes, there’s nothing that could be more elemental to the state of your community (or to the lack thereof). The roads—and the routes and the paths, the trails and the rights-of-way—take us away and they bring us home. They make us who we are and they make the places where we live.

So on this, my very first excursion, I am off into the past, kind of—to think about where we have been, as corny as it sounds. And then to come back, to return home, in this case to the city, in my case New York. In the morning, I climb into the family station wagon, and in a time-machine kind of way, I set out into the east, to New England’s (and America’s) oldest highways. For help in road explication, my destination on this roads-for-roads’-sake day is a little town in Connecticut—Guilford, the home of Dolores Hayden, a professor of architecture and American studies at Yale, and the author of such books as Redesigning the American Dream and Building Suburbia. She is a kind of naturalist of modern road-inspired building, especially with her latest book, A Field Guide to Sprawl. "Words such as city, suburb, and countryside no longer capture the reality of real estate development in the United States," she writes. Thus, she has given us a list of new ones: logo building, sitcom suburb, zoomburb.

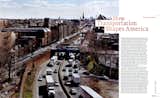

As I set out—in a very tame Kerouacian kind of way—to meet this New England-based diviner of meaning in the interstate existence, I am on a side street in New York City, a street run with row houses, delis, little stores, and restaurants, a street laid out for streetcars and horses, and taken over by the auto. Then on Atlantic Avenue, I touch the border of Brooklyn Heights, the first commuter development in New York City, an 1820s precursor of the suburb—and then in a few blocks I head onto an interstate highway, 1-278, a.k.a. the Brooklyn-Queens Expressway, a.k.a. the BQE. My soundtrack is the news radio station, blaring the traffic report that is the traffic report of all America, the car unifying us as rush-hour beings: "jammed...backed up...starting to move...bumper to bumper." I drive north, toward the Bronx, to the beginning of what in the mind of many road historians is the first modern roadway, the road that led to the interstate—the Bronx River Parkway.

The Bronx River: How not-at-all bucolic it must sound to the non-New Yorkers of America today, mostly because of the word "Bronx," a word that is derived from the name Bronck, as in Jonas Bronck, who arrived in the 17th century, and which for many years has been a synonym for urban decay and blight, in many ways because of the interstate highway system. Rest assured that when the Bronx River Parkway was begun, in 1907, it was a bucolic experience, a kind of fancy hike without any hiking. The parkway—like the parkways that would subsequently be built all around the Eastern Seaboard and then in the west—was exactly that: a way through a park, a trip along the banks of the Bronx River, an outing.

The parkway still feels bucolic, if small for a modern car. After a few minutes, I pull off to cut through a suburb, the likes of which are all over the outskirts of cities in America: see Lakewood near Cleveland, or Newton in Boston, the older suburbs that set up along the first train lines out of an old downtown. The Hutchinson Parkway, the next place I am not stopping, was built wider than the Bronx River Parkway, since roads began to kill thousands of people in the 1930s. It is almost a freeway, for the ’30s were also the time of the first freeways, as in free to not stop. The "free" replaced the "park" in terminology and in fact.

As I cross the border into Connecticut, the Hutchinson becomes the Merritt Parkway. The Merritt was built partly to relieve the traffic on Route I, the old road from Boston to Philadelphia—the oldest road, actually, officially so designated in 1673, when the main mode of travel, aside from foot, was horse. But the Merritt was also built to encourage real estate development: When the area’s property values were faltering, developers believed highways were the answer to their prayers. I stop at a little stone house rest stop befitting a highway that is a National Register of Historic Places; buy coffee from Africa via Vermont; cruise north for a few miles along the Merritt—the banked curves! the beautiful trees! the joy of cruising! the intoxicating and addictive rush!—and then cut through Westport, Connecticut, the sometime-home of Martha Stewart, to reach I-95. I-95 is so not Martha Stewart. I-95 is the longest north-to-south interstate—1,927 miles long, passing from Maine to Florida—and one of the most heavily traveled roads in America. Its rest stops, fast-food places with bathrooms larger than those in most public schools, are the loneliest places in the world.

"Well, I don’t know how you felt driving up I-95," says Dolores Hayden, just after she pulls up to the Guilford Green, "but I often feel just so dreadfully sad." She is happy-seeming now, setting out on the green. But then the green is a jewel, a mood-lifting eight-acre plot of public lawn that dates from the town’s founding in 1639. The first Guilfordians, a group of Puritans from England, grazed cattle communally and lived in thatched roofed houses along the green, a nearly medieval America. Today, to live in Guilford is mostly to commute.

But the green, crisscrossed with paths and dotted with monuments, still works, Hayden points out. High school graduations are held on the green, and in the fall there is an agricultural fair and a parade of farmers and trades, an actual medieval remnant. "That’s what makes the green seem very important in people’s lives," she says. "In other towns they’d take a piece to widen an intersection. They’d take a piece to do something else. Here they don’t." In the very center of the green, you can look past Ben Franklin’s Post Road, past houses from nearly every decade and a strip mall that was added in the ’90s, and you can see the concrete overpass of the interstate, with traffic racing by obliviously. "Sometimes when the wind is just right you can hear it," Hayden says of I-95, and she sets off on a little walk, a mile or so long, to see what roads have done and are still doing. It’s a walk to where you can't walk anymore.

We turn on Fair Street, an original street, which is fair. In sight: an 18th-century house with a 19th-century addition and a factory from the 1800s, when labor was close to consumption, when it was close to the labor force, distances that are today crossed by highways and container ships. "It’s condos now," Hayden says, "and I think [the conversion] worked pretty well." On Fair Street, the older the house, the closer it is to the road. Once, people wanted to be near the road.

This is a neighborhood that Hayden has photographed from the sky; aerial photography illustrates the pressure the highway puts on a town. "One of the better shots is looking at the size of this strip mall versus the size of these houses. The town has not been as aggressive as I would like in terms of giving people support for structures in the historic district," she says.

You can hear the suddenly speedy traffic at the corner, and see it on the old Post Road, only two lanes but fast, a race. "Okay," she says, "now here’s where we get to the point where it starts to come apart. This is where you feel like, if you’re not in your car, you’re making a mistake."

Here at Route I and Fair Street, Fair Street is no longer so fair. On the side marked "historic" is the 17th-century home of Thomas Cooke, still used, the plaque by the door noting that he arrived in 1639 by ship. Kitty-corner is a Sunoco and a Deli Unlimited, then an old school being condoized, then Tommy’s Tanning in the strip mall. "You see, it’s not like everything is going to disappear in one night," Hayden says. "It tends to just wear away at old neighborhoods. The cars and the trucks invade serenity and change its scale. It’s relentless pressure. This is not an edge to be treated lightly," she says. "I-95, once you come off it, it bleeds into the town."

Walking no longer a good idea, we get in Hayden’s car and drive down Route I, to the land where no one walks, the land that looks like everywhere, the mood changing. We drive into another strip mall, to see the expanding supermarket alongside a Dunkin’ Donuts and various chains. Hayden surveys, sadness creeping into her voice, into her professorial tone. Her car’s blinker is blinking and her head is shaking as she opines about the year the federal government changed the tax code to encourage edge-of-town development and the year that the edge-of-town-development-feeding interstate program was begun, 1954 and 1956, respectively—arcane-seeming dates that made monumental changes to the American landscape. "It [was a] direct response to feeling that the production of suburban housing might be slowing down a little bit," she says. "And instead of saying, Okay, let’s do more public housing, let’s do more inner-city preservation, they pumped money straight to the greenfield construction of supermarkets, fast-food places, chain hotels. So that’s the worst possible choice in terms of obsolescence, and in terms of moving economic activity out to beyond where the tract houses are and letting everything else go, and the roads just enhance it. That’s what was subsidized. I mean, out of all the money that could have been spent on community planning and decent architecture—it went to bogus, banal, cheap architecture."

"Yes," she says, using the words that fill her Field Guide, "the big-box, category-killer, strip-mall office-park stuff just bears down on everything. Once a community that has been around for three hundred years has been ripped apart, it’s pretty fragile," she continues. "It’s gone. You see other towns that are gone, and you see how fragile they can be. A few more gas stations and big-box stores, the scale is gone and there’s nothing left to hold onto, no sense of place and you can see towns like that all over."

From Connecticut, or anywhere in New England—or anywhere in the U.S., for that matter—there are a couple of highways to choose from if you are returning (literally or metaphorically) back to New York City, back to the present. You can take the FDR Drive, which cruises down the east side of Manhattan—a multilaned expressway that isn’t always express, due to the number of cars. Or you can take the West Side Highway. The West Side Highway was supposed to be an interstate; in plans it was I-478 and referred to as Westway, but then in the ’8os, when the tide was turning against new interstates and people were protesting what interstates had already done, it was killed. After decades of squabbling, the West Side Highway was made into a different kind of highway—a Lessway, as it is sometimes called. And it is near the corner of the West Side Highway and Gansevoort Street that I meet Andy Wiley-Schwartz, vice president for transportation of Project for Public Places, who is out of the car and who will cross the West Side Highway on foot, and on purpose. "I have some nice things to say about that highway," he told me on the phone a day before. When I meet him downtown, he stands in the stream of Chelsea pedestrians and is, as a result, cheery.

In fact, I meet him a block away from the highway, at the intersection of Gansevoort and Ninth Avenue, which happens to intersect as well with Little West 12th Street, in a cobblestone square, an accidental piazza that has Wiley-Schwartz pretty revved up—he is an evangelist of the foot. "Isn’t this great?" he says. He’s talking about the place, the street, the intersection. "Watch this," he continues. "The sidewalk is here but the desire line is there." "Desire line" is Wiley-Schwartz’s term for the way people really want to walk, despite what traffic engineers suggest. He points from the far corner and draws an imaginary line across the cobblestones at the end of Ninth Avenue, from the French restaurant toward the haute-cool Hotel Gansevoort.

Wiley-Schwartz is an intellectual descendant of William H. Whyte, a writer and researcher who, in the late ’60s, began to study the way people used streets and public places. Whyte analyzed jaywalking, for instance, and the way people greeted each other on the streets, the so-called schmooze—work with charts and time-lapse photography that eventually led to his book City: Rediscovering the Center. "What attracts people most, it would appear, is other people," Whyte wrote. Today, the Project for Public Spaces brings Whyte’s tools and thinking to cities around the country: to consider parking in Buffalo (where more than half of downtown space had been allocated for parking lots and garages); to the rethinking and reformulation of El Camino Real in San Mateo, California; and to Bryant Park, once a drug dealer’s paradise in Midtown Manhattan, now a lunchtime pedestrian’s oasis. "Organization has been made by man; it can be changed by man," Whyte said.

"So the sidewalk should be out here," where he’s walking, explains Wiley-Schwartz. At that, a woman walks from the south, walks the same exact way. "You know, you don’t have to elevate the automobile," he says. "If you can just get [drivers] to come through here on your terms, then they’ll make eye contact with all the pedestrians and everything will be much safer." Wiley-Schwartz then makes a point that is the opposite of what the first interstate highway builders had in mind. "The street needs to be designed for all users," he says. "A street is a public space."

Wiley-Schwartz comes prepared in cap and wind-breaker, toting a biography of famed historian and urban theorist Lewis Mumford, which he has been reading on the subway. And as we stand at the corner of Horatio Street and the West Side Highway, cars are rushing past at 50 miles an hour. "Right here, it doesn’t feel like it," Wiley-Schwartz says, over the wind, "but I think this is major progress."

The traffic light changes. He crosses. Three lanes, landscaping, three lanes, another landscaped berm, then a bike trail, a pedestrian trail, a ribbon of parks, and the water. "Of course, it takes a big draw to get people across the highway," he continues, "and that’s this park." We face the Hudson River.

For the record, Wiley-Schwartz is not anti-car. He drives. But he likes the West Side Highway for the way it tempts drivers with non-car related activity. "You have to create an experience for drivers as well, where they understand their part of the bargain," he says. "People make decisions about mode. Transportation designers think that people are always going to choose their cars. People aren’t given choices. But the thing is, I don’t always drive the shortest way."

We walk a few blocks south, the Hudson River sparkling on our right, the roadway moving on our left. While critics insist that the West Side Highway will have to be rebuilt to accommodate future traffic needs, Wiley-Schwartz argues that traffic needs are created by the creation of roads and parking. In his Brooklyn neighborhood he visits neighborhood groups who think that the way to solve parking problems is to add parking—this in what he calls "the most walkable city in the world." "People just don’t get that if you build faster roads and you build more parking, there will be faster roads and more parking," he says.

We cross the highway, in front of the recently built Richard Meier glass towers on Charles Street. The architecture of the road is banal box stores; the architecture of a park full of pedestrians is beautiful buildings. "Without the park, these buildings would not be here," Wiley-Schwartz says. From Meier’s own description: "The relative narrowness of the Charles Street site dictates a more contained approach."

Then we head to Wiley-Schwartz’s office, on Broadway, part of that same pre-I-95 Route I that Ben Franklin ran to Connecticut. We cross the Village on Bleecker, businesses thriving in the run of people and slow-moving cars. And then, after another block, and then a left and a right, as the blocks and the streets continue to shrink and nearly hug the walker—i.e., me—we come into the opening at the end of Fifth Avenue, which is Washington Square Park. Wiley-Schwartz stops, points, and I realize my trip into the history of roads is over. "You know, there used to be a street right there," he says. He is pointing to a wide park entry, to what is now a way to walk, the ghost of the dead street bookended by old fountains. "It went away and the world didn’t stop," he says.

Published

Get the Dwell Newsletter

Be the first to see our latest home tours, design news, and more.