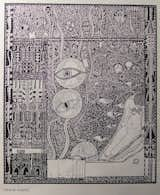

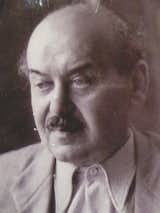

Lajos Kozma, Hungarian Modernist

Hungarian architect and designer Lajos Kozma (1884–1948) made an indelible mark on early-20th-century European design with his drawings, buildings and furniture that drew upon traditional Hungarian motifs yet showed an unprecedented bent toward modernism. Born in the small village of Kiskorpad, Kozma traveled to Budapest around the turn of the 20th century to study architecture at Budapest Imperial Joseph College. After graduating, he joined the “Young Ones,” a group of designers who studied Hungarian folk art and architecture and created furniture. “But they couldn’t get commissions,” notes Judith Hoffman, a Kozma collector and owner of Szalon in Los Angeles. “Kozma was young, he was Jewish, and he had these new ideas in very conservative times.” Following the model set by the Wiener Werkstätte (Vienna Workshop), formed in 1903 to promote Austrian art and craftsmanship, in 1913 Kozma formed the Budapest Muhely, or Budapest Workshop. Click through the slideshow below to see Kozma’s designs, as well as a selection of his drawings and buildings.