Jackson, WY

In the late 1800s, many disenchanted Wyoming homesteaders seized upon the opportunity to earn money by opening their homes to wealthy Easterners, turning their failing ranches into tourist attractions and saving themselves from a largely unfarmable landscape. More than 100 years later, Jackson, Wyoming, still hosts a number of wealthy tenderfeet, many of whom are trading in their tourist badges for part-time residency as profit-hungry developers clamor to accommodate them. For architects living, working, and building in Jackson, this often translates into a battle of design versus provincial style, cost of living versus living wage—not to mention the difficulty of pioneering change in a place where the pioneering spirit has, to some extent, become a parody of itself.

Spring has just arrived in Jackson, and judging by the number of sunburns, everyone is relieved. The energy in the office of Carney Architects stands in stark contrast to the rest of the town, where the soporific off-season is currently holding court; Snow King ski resort looks like a much-loved teddy bear as the last patches of snow pop out against the dull hills like distended cotton stuffing. At the firm a flurry of bright faces move about the floor, large tables crowd with bodies, plans, models, and material samples—clearly the off-season doesn’t exist here.

I meet first with the founding partner of Carney Architects, John Carney, who takes me to 199 East Pearl Avenue, the firm’s ambitious redevelopment loft project, whose intial phase was recently completed. The mixed-use building clad in cedar and corrugated copper sits near the town center. Carney tells me that the structure consists of 7,500 square feet of office space, two deed-restricted housing units, and six market-rate units. The first tenant is August Spier, a local restaurateur, who, by walking to and from work, uses the residence as Carney had intended it—like an urban dwelling. Carney is proud of the fit. "We immediately thought of August for the place," he explains as we walk over to another of the building’s occupied units. The place is larger than August’s and is empty save for two bottles of champagne in the fridge, some beleaguered furniture, and a few errant books on the shelves. Who lives here? I wonder. But given Jackson’s proliferation of seasonal housing, the better question is undoubtedly not who, but when?

As we make our way back to the office, we are circumvented by a man on a bike who goads Carney (in an affable, neighborly way) for blocking his view of the sunset. Up the road, construction is under way on the Jackson Hole Center for the Arts’ performing arts wing, a collaborative project between Stephen Dynia Architects and Carney Architects. It is the tallest building in Jackson, and its concrete vertical axis perfectly obscures the dip in the mountains where the sun goes down—at least from this vantage point.

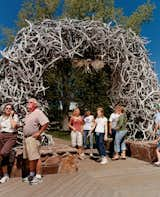

After serving as county planning commissioner for five years, Carney seems unfazed by this sort of dialogue—as much accustomed to exchanging pleasantries about the weather (which he does with seemingly everyone we pass) as he is volleying on market values and development strategies. The community’s engagement in these discussions is imperative, as a certain degree of vigilance is required to stay afloat in a housing market where the median price of a home is $1.53 million and the projected median income of a two-person household is only $59,625. This competitive, high-stakes market breeds a certain degree of antagonism toward new or divergent development for fear of losing the town’s Western mystique and bringing down neighboring property value. This traditional-at-all-costs approach has proven to be lucrative but, over time, has become parroted and campy, with elk antlers piled in archways and sticking off the side of, well, everything.

"We call them all hat, no cattle," explains Andy Ankeny, referring to the influx of wealthy faux cowboys who "keep it real" in their big-brimmed hats and H2s. Ankeny, an architect at Carney, grew up in Jackson and moved back after getting his degree in Bozeman, Montana. Most of Ankeny’s family still lives in town, and he points out Jackson’s last ranches as we drive around to look at various projects. Keying in a code to open the gate to a private community that houses one of his projects, he recalls, "Before this was gated up, we’d come here in the winter. I had a big old Dodge truck and we’d tie about six ropes to the back and attach them to the sleds and pull each other going about 30." Ankeny drives a Subaru and dresses in khaki shorts and a polo shirt. By my standards, he seems to be keeping it pretty real.

Like many of the architects at Carney, Ankeny and his wife, Shawn (also an architect), applied with the Teton County Housing Authority for a deed-restricted home (the equivalent of Section 8 housing in most areas, but obviously working from a different income scale) back in 2000. The program was designed to protect the county from "Aspenizing," an anthimeria coined for the Colorado town whose unchecked marginalization of its middle class is notorious. In Jackson, many workers make the drive over the pass from Idaho, due to the high cost of living in the town proper. "If everybody who worked here had to drive an hour to their home in another state, we’d have problems with the schools and the infrastructure," Ankeny relates.

While the Housing Authority does its best to protect the local area by only accepting applications from people with a proven commitment to the community, it doesn’t oversee CC&Rs (covenance conditions and restrictions) or homeowners’ associations, which are committees within a subdivision that rule on the aesthetic merits of every project built within its jurisdiction. And with 97 percent of the land in Teton County under natural protection (and off-limits to development), it’s pretty much guaranteed that any land purchased will reside within a subdivision.

Ankeny describes the process of working through his CC&Rs—meetings at which he and his wife were the only architects present. If incorporated, the arbitrary edits to their plans would have driven up building costs, which, for a house whose value has been capped by the Housing Authority (and which will appreciate essentially at the rate of inflation), was detrimental both fiscally and aesthetically. "Basically they’re trying to mandate against nice, beautiful, clean-lined modern stuff because they think it’s ‘boring’ and it would bring the property values down for everybody else," says Ankeny. "But the funny thing is, they still get very bland projects. They think that they’re regulating against that, but they’re not; you can’t regulate design."

Battles inevitably ensue when it comes to progressive building in Jackson, and in Eric Logan’s experience, sometimes the fights are expensive. Logan, a partner at Carney, credits architects like Will Bruder (who has designed a handful of projects in Jackson) for paving the way for modern design in the area, all the while remaining completely modest about his own contribution to the change that’s taking place, a lot of which has cost him more than just his time and energy. Logan’s CC&R committee was so enraged by his home’s simple box structure and corrugated steel that he received threatening phone messages on a regular basis. When he turned his back on an initial plan to use wood elements in his garage in favor of an all-metal structure, he was sued. "I had one guy call me and ask, ‘Boy, why in the world would you want so many windows?’" relates Logan with a rueful smile. One look at his home, which rests at the basin of the Grand Teton National Park, and the answer is self-evident.

Perhaps it was a reward for all his trials that Logan landed the job for Katherine and Carson Stanwood’s residence. The couple, who purchased the lot with a preexisting structure, wanted something smaller than the original house (which was moved and has a new home in town). In an area where 9,000-square-foot composite log homes are a norm and there’s economic incentive to build big, this is no small feat. To further confound, Logan managed to keep the Stanwoods on budget with the 2,200-square-foot house pricing in at about $160 per square foot—about half the going rate in Jackson.

Being around Logan and Carson, I start to feel like I’m in a meeting for a mutual admiration club; both architect and resident seem to think the other is the best. The truth is, they’re both pretty cool. The Stanwoods have carved out a niche for themselves (Katherine runs a high-end boutique in town and Carson does PR for a variety of sports-related merchandise), building responsibly and thoughtfully in a place that they, like so many others before, have discovered and made their own. Of course, none of this would be possible without people like Logan, whose gumption and architectural vision will, in the end, be the only things that keep Jackson from being swallowed up by its conception of itself. Both agree it was a copacetic union, as Carson tells it: "When I first talked to Eric, I think his wife was pregnant with their second child and he didn’t want to take on the project; he said, ‘Ah, I can’t do this project, I’d like to, but, but ahh … ’ Then my wife said, ‘You know, we don’t have a homeowners’ association; you could put a pagoda up here if you wanted to.’ Needless to say, Logan found the time."

Eric Logan's guest house is adjacent to his family’s home. The interiors are made up of oiled masonite wall paneling, raw MDF cabinetry, and an oiled concrete floor.

The simple agrarian structures that dot the empty fields and ranches throughout Jackson stand as inspiration to many architects who are fighting to maintain the simplicity and beauty of vernacular buildings.

Located in a 280-lot subdivision composed of market-rate and deed-restricted lots, Andy Ankney’s 1,400-square-foot house blends in well despite its large aluminum clad wood windows, cedar siding, Cor-Ten corrugated roofing, and oxidized steel siding panels.

Light pours into the Ankneys’ living/dining area with its clear pine plywood ceiling, clear-finish MDF paneling on the walls, and reclaimed-fir flooring.

A raised oxidized-steel-grate walkway provides a low-impact, richly textured alternative to the traditional stone walkway.

Architect Eric Logan sits in the guest house on his property. The interiors are made up of oiled masonite wall paneling, raw MDF cabinetry, and an oiled concrete floor.

The simple frame of the Stanwood residence is clad with oxidized steel finished with linseed oil and outfitted with Sierra Pacific windows and doors.

Published

Last Updated

Get the Dwell Newsletter

Be the first to see our latest home tours, design news, and more.