Design Icon: 8 Works by Buckminster Fuller

"I seem to be a verb," he once said. Even more than 30 years after his passing, when the magnificent machine that was Buckminster Fuller’s mind stopped minting ideas and inventions at a prodigious rate, there's still a sense that he is always in motion, moving too fast for the rest of us. You can call Richard Buckminster Fuller many things: a prophet of environmentalism and the counter-culture, decades ahead of the fringe; a Doc Brown of design thinking, whose buoyant optimism held firm to the idea humanity can innovate out of its problems; or simply a self-made genius. But most just called the inspirational thinker "Bucky."

A Young Buckminster Fuller

"The things to do are: the things that need doing, that you see need to be done, and that no one else seems to see need to be done."

Fuller’s formative years offer a glimpse of the type of thinker he would become; nonconformist (he was expelled from Harvard twice) and intuitive (he created a winch to rescue downed planes while in the Navy, and developed a new method to build reinforced concrete housing with his father-in-law). But his beliefs were truly forged during the Lake Michigan incident. Jobless at 32 with a family to support, he paced around the Chicago lakefront, contemplating suicide. Then, he had an epiphany. You can’t get rid of yourself, you have a responsibility to others—"you belong to the universe."

Dymaxion House

Inspired by the look and energy efficiency of a grain silo, Fuller’s plan for affordable housing introduced his ideas of sustainability, as well as his famous portmanteau (dynamic, maximum and tension) to the world. Developed in the 20s—it debuted at Chicago’s famous Marshall Field’s department store—it looks more imaginative than the most outlandish space serials and pulp comics. But behind the striking appearance is a quantum leap in efficiency. The entire single-family aluminum home could be flat-packed in a metal tube, a rotating "O-Volving" shelf system stores items out of sight, and the Dymaxion bathroom supposedly provided a warm shower with a mere cup of hot water. Only a few prototypes were built, including the Wichita House, which was re-assembled and is now displayed at the Henry Ford Museum.

Fuller embarked on a long path of philosophizing and designing solutions that would turn him into a global educator and icon. Innovations such as the geodesic dome and the Dymaxion Map followed, as well as the promotion of a worldview that advanced utopian thinking and efficiency. He even preached his beliefs from his gravestone, etched forever with the phrase "call me trimtab," a reference to a small flap on ship’s rudder that ultimately steers the boat. Bucky saw himself, and others like him, in that little flap; committed, ecstatic, and global thinkers who could, by force of will, change the direction of our spaceship Earth.

Dymaxion Deployment Unit

Built for the Army in WWII, these tube-like corrugated steel shelters were inspired by a quixotic journey through the Midwest. Fuller and a friend, road tripping in search of unknown letters by Edgar Allen Poe, were struck by the site of metal grain silos lining the road. Inspired, Fuller began working with the manufacturer, Butler Manufacturing, and soon, $1,250 Dymaxion Deployment Units were being built and shipped starting in April of 1941, complete with appliances and furniture by Montgomery Ward. One was displayed in MoMA’s front yard, and the army ordered more than 100 for deployment around the globe. Fuller imagined them as cheap family dwelling and potential post-war vacations homes, but the wartime steel shortage halted further production.

Geodesic Dome

German engineer Walter Bauersfeld can take credit for erecting the first geodesic dome in 1926, a replica of the night sky that glowed with nearly 5,000 stars. But Fuller’s work popularizing these hyper-efficient structures led to their mass adaptation around the world—more than 300,000 exist at last count. During a teaching stint at Black Mountain College from 1948-1949, Fuller refined synergetic geometry and the dome concept, utilizing a spherical arrangement of triangles to cover more space with less material. Bucky was soon creating domes for the U.S. military (covering, among other things, radar station in the Arctic Circle) and the Ford Motor Company, and popularizing the concept with worldwide audiences at the 1954 Milan Triennale.

Dymaxion Car

In his search for energy and engineering efficiency, it’s fitting Bucky would take on one of the ultimate symbols of consumer excess, the American automobile. Developed in 1993, the Dymaxion Car was a floor model for Fuller’s singular vision. Its long, teardrop exterior was designed with the assistance of Isamu Noguchi, and it accommodated 11 passengers while hitting top speeds of 90 mph on three wheels. But the most audacious fact about this oddball auto was its fuel efficiency, a stunning 30 mpg, decades before even the flimsiest two-seater could make a similar claim. After a test-version crashed at the 1933 World’s Fair, killing the driver, many were apprehensive about the safety of a rear-wheel driven car, and Fuller was never able to finance mass production.

Dymaxion Map

The March 1, 1943 issue of Life magazine included one of publishing’s more intriguing fold-outs; the first example of Buckminster Fuller’s Dymaxion Map. Less outlandish today, in an age of Feltron and infographic overload, Fuller’s fold-out projection was an outlier that raised serious philosophical and political points. With no fixed direction and less distortion than then-current maps, the Dymaxion Map sought to do away with judgements based on size and position, and make the underlying point that we’re all together on spaceship Earth. Fuller deliberately presented humanity as "one island, in one ocean," so we could better face our common problems together.

Montreal Biosphere

To help showcase America’s achievements at the 1967 World’s Fair in Montreal (and potentially distract crowds from the UK pavilion, manned by hostesses sporting the newly popular miniskirt), the U.S. government recruited Buckminster Fuller to design a geodesic dome. The choice proved inspired; more than 5 million traveled to the glittering American pavilion, encased in a clear acrylic cover, to see myriad displays, such as Apollo spacecraft, While it proved eye-catching during the Expo, the cover also proved extremely flammable; a fire reduced the dome to a mere steel skeleton in 1976. In a meaningful tribute to Fuller’s legacy, the site has since been turned into an environmental museum.

Fly’s Eye Domes

Fully realized during the last few years of his life, these "autonomous dwellings" were the culmination of all his learning and experience, according to Fuller. The "fly’s eye" holes can be used as doors or outfitted with wind or solar power to create off-the-grid housing. The largest model, a 50-foot-high dome, debuted in LA in 1981 and was out-of-sight for decades before being restored and shown at the Toulouse International Art Festival last year.

World Game

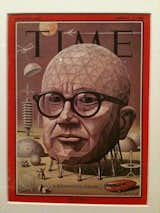

"Make the world work, for 100% of humanity, in the shortest possible time, through spontaneous cooperation, without ecological offense or the disadvantage of anyone." While Fuller’s ultimate goal was audacious, the idea of a real-time simulation in the ‘60s, accessible to before widespread access to computing, was just somewhat less ambitious. Fuller’s game—so-called to be accessible to everyone—was a further expansion of his Spaceship Earth philosophy, and is currently being utilized as a model by the O.S. Earth Institute. (Pictured: Bucky's Time cover from 1964.)

Published

Last Updated

Get the Dwell Newsletter

Be the first to see our latest home tours, design news, and more.