Fred Fisher on A. Quincy Jones

A. Quincy Jones was a mid-century modernist whose architecture knew no bounds. He designed custom homes for the rich and famous, affordable tract houses, churches, restaurants, libraries, laboratories, university campuses, a factory and an embassy. He also taught, extending his considerable influence to a generation of younger designers. After languishing on the market since 2008, Jones’ Los Angeles home was purchased by the Annenberg Foundation earlier this year, ensuring that it will be preserved. When work is completed at the end of the summer, “the Barn” – as the structure is known – will serve as headquarters of the Chora Council, which is part of the Metabolic Studio, a multi-disciplinary Annenberg project devoted to the study of culture, sustainability and health. AIA award-winning architect Frederick Fisher, who has occupied Jones’ nearby business offices since 1995 and refreshed other Jones projects, is overseeing the restoration with contractor George Minardos. Here, Fisher tells us about saving the residential landmark.

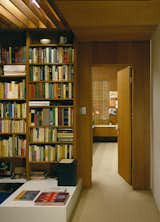

What’s happening at the Barn?We’re doing a very light-touch renovation/rehabilitation. It’s a 60-year-old wood building in Century City that was designed as a photographer’s studio in 1950 and then bought and remodeled by Jones in 1965. His previous house had burned down in one of the hillside fires. He elected to buy the Barn and remodel it because of its proximity to his offices two miles away on Santa Monica Boulevard. It had systems issues that needed to be updated, so we’re carefully fitting in things like new electrical, air conditioning, plumbing and wiring within the existing framework. But by and large, the look of the place inside and out will be the same.Who’s spearheading the effort?Lauren Bon, the daughter of Wallis Annenberg and an Annenberg Foundation director, is the driving force. She has an interest in furthering the legacy of the foundation and its connection to Quincy Jones’ architecture. The Annenberg estate at Rancho Mirage was Quincy Jones’ largest residential project. He also designed the Annenberg School of Communications at USC. She sees the acquisition of this building like acquiring a work of art, so much of the furniture and even the art, books and artifacts were also acquired in a separate transaction. Her focus has been, to the greatest degree possible, to preserve the integrity of the building and use it as it has always been, as a live-work environment.Have there been any surprises?We learned the original builder was Craig Ellwood before he had his career as an architect [who designed two Case Study houses and Art Center College of Design in Pasadena]. That was an unexpected bit of trivia.Jones designed his architectural offices, and you rescued them from likely demolition. Why save the Barn if Jones didn’t create the original structure?Quincy Jones was one of the premiere California modernists out of the Case Study era, part of the second generation after Schindler and Neutra. The Barn was remodeled by him and so it has a very distinctly A.Q. Jones feel to the interior. It was his place of residence, his workplace and a place where many of the activities revolved around his being dean of the School of Architecture at USC. When you’re in that building, you really feel you’re in the environment of two very sensitive, design-oriented people. Elaine Jones, his wife, worked with Herman Miller. She and Quincy were friends of Charles and Ray Eames. So it’s not only a design environment. When you’re in it, you’re very much immersed in the ’60s and ’70s design ethos and in a piece of cultural history as well.How did Jones modify the building?It was originally a wood barn, literally a red barn. He painted it white. The narrow slat sun shades that he put on the outside of the windows modernized it and warmed it up. Inside, the plan of the building is this tall, two-story atrium space with mezzanines that wrap around three sides. One side is the living area, with sleeping quarters upstairs. The opposite was an office area with worktables and files. Those spaces look through windows without glass into the main space so it’s almost like you’re looking at two buildings in a courtyard. The third side is an open mezzanine of another work area that connects the other two spaces. Jones’ cabinetry and the architectural armatures – the built-in furnishings, mezzanines and staircases – were made of materials such as rough-sawn redwood plywood, a very common material at the time. There’s obscure glass in the entry vestibule surrounding an indoor planter. Indoor landscaping was a signature of A.Q. Jones. Are there any similarities between the Barn and the architectural offices?Quincy Jones worked with what you might call a warm modernism. He liked organic materials and so my office floor is concrete with river pebbles seeded into it with redwood battens laid in it at about three-foot intervals. There are indoor planters, a lot of exposed structure, a lot of exposed wood. His style wasn’t the same as the abstract European modernism, where it’s the white surfaces, metal and white plaster you’d see with Neutra. It was more out of the Wrightian tradition of organic modernism, with a particular emphasis on wood. The continuity of space, the flowing space, is certainly a trait of both buildings. And there’s a strong relationship between indoors and outdoors. He liked bringing the garden inside the building and having living spaces flow from the inside out. What lessons can be learned from the adaptive reuse of the Barn?The house is a good example of a live-work environment. There’s a lot of talk now about the creative workspace and incubator spaces. I see it as an incubator space before there was a name for it. It can be a workspace, a living space, an entertaining space, all in a very accommodating way. It’s in the tradition of the loft space, where artists have always been good at ferreting out live-work spaces that are under-appreciated or under-utilized. It’s neutral, mutable space that can be used in many different ways by a creative mind. It’s a good model for that and still quite relevant.