How New York City Developed its Wayfinding Signage

Our City Living issue, due out on newsstands September 10, focuses on design and architecture in urban locales. Here we turn our eye to the challenges of navigating a city and how graphic design can improve the experience, especially when it comes to walkability. As more cities seek to encourage multi-modal transportation—walking, biking, public transit, etc.—the need for good signage to make those activities easier becomes more and more apparent. At its simplest, wayfinding is defined as spatial problem solving—knowing where you are, where you want to go, and the best route to get there. Cartography, or mapmaking, has existed for thousands of years, tracing its roots to cave paintings, but the demands of modern cities and diverse populations call for more than a sign emblazoned with compass rose and a few street names. Today, effective urban maps require layers of information relayed in a clear, consistent, and concise manner so that anyone can quickly assess how to get from point A to point B.

The New York Department of Transportation launched its WalkNYC program in the summer of 2013 to "provide a clear visual language and graphic standards that can be universally understood, encourage walking and transit usage by offering quality multi-modal information, and provide consistent information across a broad range of environments in the city." Lauded design firm Pentagram's PentaCityGroup developed the identity. We sent a few queries to Michael Bierut, a graphic designer and partner at the firm, to lean more about the program, what it means for the city's identity, and how technology does and doesn't factor into the program. "I feel strongly that one of the best things about the signs are that you don't need a smart phone to access them: they're right there on the street, as democratic as can be," he says. Read on for more.

![Dwell: How did Universal Design factor into WalkNYC?

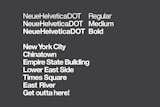

Bierut: We did a lot of readability tests when we were picking the type sizes and color combinations [the color palette is shown in this slide] to make sure the information was as legible as possible. And I feel strongly that one of the best things about the signs are that you don't need a smart phone to access them: they're right there on the street, as democratic as can be.](https://images2.dwell.com/photos/6063391372700811264/6133564271322968064/original.jpg?auto=format&q=35&w=160)