True Hollywood Story

Even if you’re confused by the fork in the driveway, which slopes up to the Edenic apex of Laurel Canyon, or don’t recognize architect Raphael Soriano’s mid-century design landmark, you can’t miss Julius Shulman’s place. It’s the one with the eight-foot-high banner bearing his name—an advertisement for his 2005 Getty Museum exhibition "Modernity and the Metropolis"—hanging before the door to the studio adjoining the house. As displays of ego go, it’s hard to beat. Yet the voice calling out from behind it is friendly, even eager—"Come on in!" And drawing back the banner, one finds, not a monument, but a man: behind an appealingly messy desk, wearing blue suspenders and specs with lenses as big as Ring Dings, and offering a smile of roguish beatitude.

"A wonderful mess" is how Shulman describes his desk. Interspersed among the family snapshots, mementos, and tchotchkes are several enlarged quotations, including one from Art News: "If buildings were people, those in Julius Shulman’s photographs would be Grace Kelly: classically elegant, intriguingly remote."

You’d smile, too. At 96, Shulman is the best known architectural photographer in the world, and one of the genre’s most influential figures. Between 1936, when a fateful meeting with architect Richard Neutra began his career, and his semi-retirement half a century later, he used his instinctive compositional elegance and hair-trigger command of light to document more than 6,500 projects, creating images that defined many of the masterworks of 20th-century architecture. Most notably, Shulman’s focus on the residential modernism of Los Angeles, which included photographing 18 of the 26 Case Study Houses commissioned by Arts & Architecture magazine between 1945 and 1967, resulted in a series of lyrical tableaux that invested the high-water moment of postwar American optimism with an arresting, oddly innocent glamour. Add to this the uncountable volumes and journals featuring his pictures, and unending requests for reprints, and you have an artist whose talent, timing, ubiquity, and sheer staying power have buried the competition—in some cases, literally.

"I'm always identified as being the best architectural photographer in the world," declares Shulman. "I disclaim that. I say, 'One of the best.'" The photographer paid $2,500 for his two-acre property, and $40,000 for the Raphael Soriano–designed studio and house, into which he moved in 1950. "All in cash," Shulman says. "My mother taught us, 'Never have a mortgage.'" Over the ensuing decades, he says, "I planted hundreds of trees and shrubs, to emulate how I lived as a child [on a farm in Connecticut]."

Shulman’s decision to call it quits in 1986 was motivated less by age than a distaste for postmodern architecture. But, he insists, "it wasn’t quite retiring," citing the ensuing decade and a half of lectures, occasional assignments, and work on books. Then, in 2000, Shulman was introduced to a German photographer named Juergen Nogai, who was in L.A. from Bremen on assignment. The men hit it off immediately, and began partnering on work motivated by the maestro’s brand-name status. "A lot of people, they think, It’d be great to have our house photographed by Julius Shulman," says Nogai. "We did a lot of jobs like that at first. Then, suddenly, people figured out, Julius is working again."

At Shulman’s insistence, Soriano created a screened area that protects the gardenside elevation of the house from, says the photographer, "excessive wind and glaring light. In hot weather, when I have the sliding glass doors open, I close the screens on the sides—otherwise it’s all open to the coyotes and raccoons." In keeping with the off-the-shelf ethic of the Case Study era, Soriano used simple, durable materials that, after 57 years, remain intact.

"I realized that I was embarking on another chapter of my life," Shulman says, the pleasure evident in his time-softened voice. "We’ve done many assignments"—Nogai puts the number at around 70—"and they all came out beautifully. People are always very cooperative," he adds. "They spend days knowing I’m coming. Everything is clean and fresh. I don’t have to raise a finger." As regards the division of labor, the 54-year-old Nogai says tactfully, "The more active is me because of the age. Julius is finding the perspectives, and I’m setting up the lights, and fine-tuning the image in the camera." While Shulman acknowledges their equal partnership, and declares Nogai’s lighting abilities to be unequaled, his assessment is more succinct: "I make the compositions. There’s only one Shulman."

"No landscape architect would do this mishmash," says Shulman of his beloved garden. "Behind my land is 53 acres, which now belong to the Santa Monica Conservancy, so it's protected," he says. "My daughter's son will probably live here when he grows up—he's only 25 or 30 now." Though the photographer uses a walker—dubbed "the Mercedes"—to maintain his balance, he claims to have given up skiing and backpacking in the Sierras only a few years ago.

In fact, there seem to be many. There’s Shulman the photographer, who handles three to five assignments a month (and never turns one down—"Don’t have to. Everyone’s willing to wait"), and the Shulman between hard covers, whose latest book, the three-volume, 950-page Modernism Rediscovered, will shortly be published by Taschen. But the Shulman of whom Shulman seems most proud is the educator. In 2005, he established an eponymous institute in conjunction with the Woodbury University in nearby Burbank, to provide, according to the school, "programs that promote the appreciation and understanding of architecture and design." Apart from a fellowship program and research center, the Julius Shulman Institute’s principal asset is its founder, who has given dozens of talks at high schools across Southern California.

"The subject is the power of photography," Shulman explains. "I have thousands of slides, and Juergen and I have assembled them into almost 20 different lectures. And not just about architecture—I have pictures of cats and dogs, fashion pictures, flower photographs. I use them to do a lot of preaching to the students, to give them something to do with their lives, and keep them from dropping out of school."

It all adds up to a very full schedule, which Shulman handles largely by himself—"My daughter comes once a week from Santa Barbara and takes care of my business affairs, and does my shopping"—and with remarkable ease for a near-centenarian. Picking up the oversized calendar on which he records his appointments, Shulman walks me through a typical seven days: "Thom Mayne—we had lunch with him. Long Beach, AIA meeting. People were here for a meeting about my photography at the Getty [which houses his archive]. High school students, a lecture. Silver Lake, the Neutra house, they’re opening part of the lake frontage, I’m going to see that. USC, a lecture. Then an assignment, the Griffith Observatory—we’ve already started that one."

Yet rather than seeming overtaxed, Shulman fairly exudes well-being. Like many elderly people with nothing left to prove, and who remain in demand both for their talents and as figures of veneration (think of George Burns), Shulman takes things very easy: He knows what his employers and admirers want, is happy to provide it, and accepts the resulting reaffirmation of his legend with a mix of playfully rampant immodesty and heartfelt gratitude. As the man himself puts it, "The world’s my onion."

Given the fun Shulman’s having being Shulman, one might expect the work to suffer. But his passion for picture-making remains undiminished. "I was surprised at how engaged Julius was," admits the Chicago auction-house mogul Richard Wright, who hired Shulman to photograph Pierre Koenig’s Case Study House #21 prior to selling it last year. "He did 12 shots in two days, which is a lot. And he really nailed them." Of this famous precision, says the writer Howard Rodman, whose John Lautner–designed home Shulman photographed in 2002: "There’s a story about Steve McQueen, where a producer was trying to get him to sign on to a movie. The producer said, ‘Look how much you change from the beginning to the end.’ And McQueen said, ‘I don’t want to be the guy who learns. I want to be the guy who knows.’ And Shulman struck me as the guy who knows."

This becomes evident as, picking up the transparencies from his two most recent assignments, he delivers an impromptu master class. "We relate to the position of the sun every minute of the day," Shulman begins, holding an exterior of a 1910 Craftsman-style house in Oakland, by Bernard Maybeck, to the lamp atop his desk. "So when the sun moves around, we’re ready for our picture. I have to be as specific as a sports photographer—even a little faster," he says, nodding at the image, in which light spills through a latticework overhang and patterns a façade. "This is early afternoon, when the sun is just hitting the west side of the building. If I’m not ready for that moment, I lose the day." He does not, however, need to observe the light prior to photographing: "I was a Boy Scout—I know where the sun is every month of the year. And I never use a meter."

Shulman is equally proud of his own lighting abilities. "I’ll show you something fascinating," he says, holding up two exteriors of a new modernist home, designed for a family named Abidi, by architect James Tyler. In the first, the inside of the house is dark, resulting in a handsome, somewhat lifeless image. In the second, it’s been lit in a way that seems a natural balance of indoor and outdoor illumination, yet expresses the structure’s relationship to its site and showcases the architecture’s transparency. "The house is transfigured," Shulman explains.

"I have four Ts. Transcend is, I go beyond what the architect himself has seen. Transfigure—glamorize, dramatize with lighting, time of day. Translate—there are times, when you’re working with a man like Neutra, who wanted everything the way he wanted it—‘Put the camera here.’ And after he left, I’d put it back where I wanted it, and he wouldn’t know the difference—I translated. And fourth, I transform the composition with furniture movement."

To illustrate the latter, Shulman shows me an interior of the Abidi house that looks out from the living room, through a long glass wall, to the grounds. "Almost every one of my photographs has a diagonal leading you into the picture," he says. Taking a notecard and pen, he draws a line from the lower left corner to the upper right, then a second perpendicular line from the lower right corner to the first line. Circling the intersection, he explains, "That’s the point of what we call ‘dynamic symmetry.’" When he holds up the photo again, I see that the line formed by the bottom of the glass wall—dividing inside from outside—roughly mirrors the diagonal he’s drawn. Shulman then indicates the second, perpendicular line created by the furniture arrangement. "My assistants moved [the coffee table] there, to complete the line. When the owner saw the Polaroid, she said to her husband, ‘Why don’t we do that all the time?’"

Shulman’s remark references one of his signature gambits: what he calls "dressing the set," not only by moving furniture but by adding everyday objects and accessories. "I think he was trying to portray the lifestyle people might have had if they’d lived in those houses," suggests the Los Angeles–based architectural photographer Tim Street-Porter. "He was doing—with a totally positive use of the words—advertising or propagandist photographs for the cause." This impulse culminated in Shulman’s introduction of people into his pictures—commonplace today, but virtually unique 50 years ago. "Those photographs—with young, attractive people having breakfast in glass rooms beside carports with two-tone cars—were remarkable in the history of architectural photography," Street-Porter says. "He took that to a wonderfully high level."

Surprisingly, Shulman underplays this aspect of his oeuvre. The idea, he explains, is simply to "induce a feeling of occupancy. For example, in the Abidi house, I put some wineglasses and bottles on the counter, which would indicate that people are coming for dinner. Then there are times I’ll select two or three people—the owner of a house, or the children—and put them to work. Sometimes it’s called for."

"Are you pleased with these photographs?" I ask as he sets them aside. "I’m pleased with all my work," he says cheerfully.

"I tell people in my lectures, ‘If I were modest, I wouldn’t talk about how great I am.’" Yet when I ask how he devel-oped his eye, Shulman’s expression turns philosophical. "Sometimes Juergen walks ahead of me, and he’ll look for a composition. And invariably, he doesn’t see what I see. Architects don’t see what I see. It’s God-given," he says, using the Yiddish word for an act of kindness—"a mitzvah."

I suggest a tour of the house, and Shulman moves carefully to a rolling walker he calls "the Mercedes" and heads out of the studio and up the front steps. As a plaque beside the entrance indicates, the 3,000-square-foot, three-bedroom structure, which Shulman commissioned in 1948 and moved into two years later, was landmarked by L.A.’s Cultural Heritage Commission as the only steel-frame Soriano house that remains as built. Today, such Case Study–era residences are as fetishized (and expensive) as Fabergé eggs. But when Shulman opens the door onto a wide, cork-lined hallway leading to rooms that, after six decades, remain refreshing in their clarity of function and communication, use of simple, natural materials, and openness to the out-of-doors, I’m reminded that the movement’s motivation was egalitarian, not elitist: to produce well-designed, affordable homes for young, middle-class families.

"Most people whose houses I photographed didn’t use their sliding doors," Shulman says, crossing the living room toward his own glass sliders. "Because flies and lizards would come in; there were strong winds. So I told Soriano I wanted a transition—a screened-in enclosure in front of the living room, kitchen, and bedroom to make an indoor/outdoor room." Shulman opens the door leading to an exterior dining area. A bird trills loudly. "That’s a wren," he says, and steps out. "My wife and I had most of our meals out here," he recalls. "Beautiful."

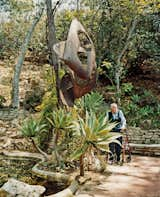

We continue past the house to Shulman’s beloved garden—he calls it "the jungle"—a riot of vegetation that overwhelms much of the site, and frames an almost completely green canyon view. "I planted hundreds of trees and shrubs—back there you can see my redwoods," he says, gesturing at the slope rising at the property’s rear. "Seedlings, as big as my thumb. They’re 85 feet tall now." He pauses to consider an ominously large paw print in the path. "It’s too big for a dog. A bobcat wouldn’t be that big, either. It’s a mystery," Shulman decides, pushing the Mercedes past a ficus as big as a baobab.

The mystery I find myself pondering, as we walk beside the terraced hillside, is the one he cited himself: the source of his talent. In 1936, Shulman was an ama-teur photographer—gifted, but without professional ambition—when he was invited by an architect friend to visit Richard Neutra’s Kun House. Shulman, who’d never seen a modern residence, took a handful of snapshots with the Kodak vest-pocket camera his sister had given him, and sent copies to his friend as a thank-you. When Neutra saw the images, he requested a meeting, bought the photos, and asked the 26-year-old if he’d like more work. Shulman accepted and—virtually on a whim—his career took off.

When I ask Shulman what Neutra saw in his images, he answers with a seemingly unrelated story. "I was born in Brooklyn in 1910," says this child of Russian-Jewish immigrants. "When I was three, my father went to the town of Central Village in Connecticut, and was shown this farmhouse—primitive, but [on] a big piece of land. After we moved in, he planted corn and potatoes, my mother milked the cows, and we had a farm life.

"And for seven years, I was imbued with the pleasure of living close to nature. In 1920, when we came here to Los Angeles, I joined the Boy Scouts, and enjoyed the outdoor-living aspect, hiking and camping. My father opened a clothing store in Boyle Heights, and my four brothers and sisters and my mother worked in the store. They were businesspeople." He flashes a slightly cocky smile. "I was with the Boy Scouts."

We arrive at a sitting area, with a small pool of water, a fireplace, and a large sculpture (purchased from one of his daughter’s high school friends) made from Volkswagen body parts. Shulman lowers himself onto a bench and absorbs the abundant natural pleasures. "When I bought this land, my brother said, ‘Why don’t you subdivide? You’ll make money.’" He looks amused. "Two acres at the top of Laurel Canyon, and the studio could be converted into a guest house—it could be sold for millions."

He resumes his story. "At the end of February 1936, I’d been at UCLA, and then Berkeley, for seven years. Never graduated, never majored. Just audited classes. I was driving home from Berkeley"—Shulman hesitates dramatically—"and I knew I could do anything. I was even thinking of getting a job in the parks department raking leaves, just so I could be outside. And within two weeks, I met Neutra, by chance. March 5, 1936—that day, I became a photographer. Why not?"

Hearing this remarkable tale, I understand that Shulman has answered my question about his talent with an explanation of his nature. What Neutra perceived in the young amateur was an outdoorsman’s independent spirit and an enthusiasm for life’s possi-bilities, qualities that, as fate would have it, merged precisely with the boundless optimism of the American Century—an optimism, Shulman instinctively recognized, that was embodied in the modern houses that became, as Street-Porter says, "a muse to him."

"[Shulman] always says proudly that Soriano hated his furniture," says Wim de Wit, the Getty Research Institute curator who oversees Shulman’s collection. "He says, ‘I don’t care; when I sit in a chair I want to be comfortable.’ He does not think of himself as an artist. ‘I was doing a business,’ he says. But when you look at that overgrown garden, you know—there is some other streak in him." That streak—the free soul within the unpretentious, practical product of the immigrant experience—produced what Nogai calls "a seldom personality": a Jewish farm boy who grew up to create internationally recognized American cultural artifacts—icons that continue to influ-ence our fantasies and self-perceptions.

I ask Shulman if he’s surprised at how well his life has turned out. "I tell students, ‘Don’t take life too seriously—don’t plan nothing nohow,’" he replies. "But I have always observed and respected my destiny. That’s the only way I can describe it. It was meant to be."

"And it was a destiny that suited you?"

At this, everything rises at once—his eyebrows, his outstretched arms, and his peaceful, satisfied smile. "Well," says Shulman, "here I am."

Published

Last Updated

Get the Dwell Newsletter

Be the first to see our latest home tours, design news, and more.