The Timeless Thrill of the Museum Period Room

There’s something vaguely, thrillingly unsettling about the 18th century bedroom from the Sagredo Palace off Venice’s Grand Canal. It’s a shade of green that verges on avocado, intertwined with gold; the ceiling is heavy with frolicking cherubs who almost begin to take on the impression of bats fluttering around a belfry, the longer you stare at them. There are windows, but they admit only artfully staged artificial light whose time of day it is difficult to place. Catching the room in a quiet moment, it feels like you’re a time traveler who’s stumbled into a grand house disrupted by some outbreak of plague. Of course, the feeling of time-slippage is all the more intense, given that anyone who is viewing it now does so in its home of New York City’s Metropolitan Museum of Art, where it has been sitting since 1926.

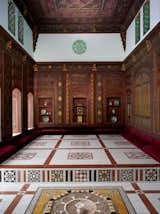

The bedroom is just one of the Met’s numerous period rooms, ranging from Pompeii to 19th century New York to 12th century Damascus, a fixture of the museum for generations. There are other period rooms scattered across the country, too, at the Brooklyn Museum, at the Philadelphia Museum of Art, at the Minneapolis Institute of Art. In the early 20th century, museums seemed to be installing them left and right; now they’re considered a bit… retro. But they still offer pleasures for anybody interested in design and its history, especially during the dog days of summer, when it’s hot and flat and it seems like nothing will ever surprise you again—until you stand staring at the Brooklyn Museum’s staggeringly over-the-top Worsham-Rockefeller Room for a few minutes. When it’s miserably steamy outside, it’s hard to fathom a better space than a low-lit, air-conditioned room from 18th century France.

And the people watching can’t be beat: young couples amble through the Met’s American Wing, trying to impress each other, men in their 20s offering up "that’s crazy, dude"-type observations to their girlfriends. On a recent trip to the Brooklyn Museum, I barely resisted the urge to trail a woman with a strong Southern accent telling her companions "it was an ugly thing, truly ugly," leaving me to guess whether she was talking about an object in the museum or something hideous from her own family history. Meanwhile, a young woman summed up the entire experience of wandering through the museum staged historical rooms—not entirely inaccurately—by saying that it was "like going to an Ikea." Visitors bring their own histories, expectations, and design assumptions to these spaces.

"We consistently get expressions of delight about the period rooms," says Jessica Smith, Director of Curatorial Initiatives at the Philadelphia Museum of Art, of feedback from visitors.

Many of America’s period rooms date from the early 20th century. "The tradition of period rooms in America is usually associated with institutions that thrived during the 1920s, when entire buildings were created and filled with rooms in such styles as ‘Early American’ ‘Colonial,’ and ‘Federal,’" wrote then-director of the Metropolitan Museum of Art Philippe de Montebello in a 1996 publication by the museum about its period rooms, citing the Winterthur Museum in Delaware, Colonial Williamsburg, and indeed the Met itself. Smith explained that the PMA’s rooms were baked into the museum from its opening in 1928 by director Fiske Kimball, an architectural historian. The very notion of the period room in America is closely linked to the "colonial revival" of the era, a period of fascination with early American history that was preoccupied with shoring up a romanticized, simplified view of the nation’s founding as urbanization and immigration transformed the country.

The bedroom from the Sagredo Palace. Per the Met, it is a reconstruction "preserved as far as possible… The window frames, the paneled wood dado, and the terrazzo floor are modern. The brocatelle on the walls is of the period but not original. The curtains are modern. The marble door-frames are almost identical with the original, but come from another building, the Palazzo Lezze."

As such, period rooms have a bit of a controversial reputation. For one thing, they’re all at least to some extent a reconstruction. For instance, the Met’s page for the Sagredo Palace bedroom carefully notes that the window frames, the terrazzo floor, and the curtains are all modern, while the marble door frames are nearly identical to the original, but from another building. The Met’s own publication admitted that, "their very existence is the subject of debate. Some scholars and experts in the field of decorative arts do not agree on their appropriateness in an art-museum setting, their purpose, and their degree of authenticity."

"Often it’s more of a mashup than I think people can imagine just by looking," says Smith. But as she pointed out, that’s how it works in real life, too. "People have objects from different periods or countries of origin. That messiness has a nice resonance with how people do live their lives." (Think of all those scenes from The Crown with Queen Elizabeth II watching a progression of ever-more-sophisticated televisions, stuck strangely into rooms at Windsor or Balmoral.)

And, too, as the architectural preservation movement gained steam in the middle of the century—the National Historic Preservation Act was passed in 1966—there was a sense that it was better to preserve a complete space as a historic house, rather than carve out a bedroom or a parlor and put it in a museum. There’s also the charge that they’re just plain old-fashioned. A 2013 New York Times piece described them as having the reputation of being "the cultural equivalent of grandma’s overstuffed couch that smelled like a fleet of cats." (Ouch.)

There’s something to be said, however, for quietly flowing through a series of moments in time and space, even if they are constructed with some artistic license. A good period room experience is almost like strolling IRL through the history of design. The ability to move from space to space offers up new contexts: walk through the American Wing and you can watch the levels of ornamentation build and build and build through Renaissance Revival and Rococo Revival and Gothic Revival, so that by the time you reach Frank Lloyd Wright’s living room from the Frank W. Little house, it feels like a fever breaking. The sheer ease of a Wright room after all those 19th century frills (notwithstanding the man’s reputation as a control freak) is enough to make you reconsider the virtues of beige, taupe, and brown, after years of modern farmhouse whitewash.

A recreation of the Drawing Room of the Craig House in Baltimore, built in the early 1800s; the "architectural elements," including the mantel, are original to the home.

Sometimes, it’s even weirder than just simply time-traveling: "We have a drawing room from a townhouse in New York, 901 Fifth Avenue," Smith explains. "It looks like an 18th century interior because it was designed in 1923 to house an 18th century collection. It’s a 20th century New York interior meant to look like a French 18th century interior."

And there are distinct pleasures for people who are interested in design. Doing research for this piece, I came across one New York Times piece where the author describes tracing the history of the sofa through the Met’s many period rooms. You could easily do the same thing with window hangings, or trying to figure out how they heated these spaces. (Anybody can romanticize a fireplace, but the Met’s Swiss room will have you yearning for a hand-painted ceramic stove.) They’re always a fascinating journey through the many ways you can assemble a space: What lines and proportions work together to create what effect? What makes a pattern read as clashing versus harmonious? Could I pull off a statement lamp? If so, what’s the statement? I dunno, maybe I could get into wall-to-wall carpet, if it was part of a perfectly realized Art Deco study.

Then, of course, there are the ruder pleasures of the period room. Specifically, the opportunity to stand there and roast the hell out of previous eras’ decorating decisions.

Take the Worsham-Rockefeller Room at the Brooklyn Museum, decorated in the late 19th century Aesthetic Movement Style, which is a nice way of saying a dizzying mishmosh of elements appropriated from Muslim Spain and north-west Africa. It’s from a New York townhouse redone in the 1880s by Arabella Worsham—the mistress of a railroad magnate. According to the Met (which now owns the also-elaborate dressing room from the same house), she’d barely finished the house when the magnate’s wife died and Worsham married him and sold the place to John D. Rockefeller, whose son eventually donated the room to the Brooklyn Museum. It’s easy to understand why Rockefeller, Jr., donated it, because I’m pretty sure when I rounded the corner and saw it, I involuntarily muttered "Jesus Christ," to myself.

The initial impression is overwhelming, full of looming dark wood and patterns on patterns on patterns. It looks like the setting for a gothic romance, like the type of place somebody might plot to poison a relative or spouse. It is an absolutely gorgeous nightmare that only the 1880s could have produced. The Rococo Revival parlor at the Met is a similar experience—it’s enough to challenge the most committed maximalist. A good period room can work like an aesthetic jump scare, forcing you to clutch your chest at the sight of a particularly aggressive carpet.

Period rooms aren’t as frozen in time as you might suspect, stumbling into an empty parlor on a quiet day. Some of that is practical; Smith described the complexities of updating the fire alarm system in a room where the ceiling itself is, in fact, part of the art. The PMA has also recently revamped their 18th century drawing room from Lansdowne House, recreating the historic carpet with a modern facsimile so that people can actually walk in and experience the room, as opposed to just walking up to a guard rail and peering in.

Some of the efforts are downright playful. The "Living Rooms" initiative at the Minneapolis Institute of Art, for instance, attempts to portray the museum’s period rooms and decorative arts in new ways, for instance transforming an 18th century French Grand Salon into an exhibition on partying all night in the 1700s. The most interesting update, however, is the Met’s addition of Before Yesterday We Could Fly: An Afro-Futurist Period Room.

The installation Before Yesterday We Could Fly "is a fabrication of a domestic space that assembles furnishings to create an illusion of authenticity."

One of the uglier facts about period rooms is the presence of spaces like the American Wing’s early 19th century Richmond Room, paneled in mahogany, which was harvested in horrific conditions by enslaved people. The simple fact is such rooms were originally included in various institutions as a monument, rather than a testament to the absolute horrors that often funded their original creation. The Met has recontextualized the Richmond Room, weaving in information about where that wood came from, and under what circumstances; "How can we have a room that’s paneled in mahogany and not talk about the reality of how this material was attained?" wrote Amelia Peck, the Marica F. Vilcek Curator of American Decorative Arts, in a piece for the Met’s website.

Before Yesterday We Could Fly takes a different approach. Rather than attempting perfect reconstruction of a moment in time, it leans into the imaginative aspect of these spaces, to evoke a dreamlike alternate history of the predominantly Black Seneca Village, which was seized under eminent domain for the creation of Central Park: "Like other period rooms throughout the Museum, this installation is a fabrication of a domestic space that assembles furnishings to create an illusion of authenticity. Unlike these other spaces, this room rejects the notion of one historical period and embraces the African and African diasporic belief that the past, present, and future are interconnected and that informed speculation may uncover many possibilities."

It’s spine-tingling in its own way, exploding the whole idea of the period room and sending fragments of the whole concept spinning out into the space-time continuum. Time travel, yet again.

Top Photo of the Tapestry Room from the Croome Court, designed in 1763, Courtesy of the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Related Reading:

Millennials Are Coming for the Tiny Collectible Christmas Village

Why the Sweet, Sweet Strawberry Motif Never Goes Out of Style

Published

Topics

LifestyleGet the Dwell Newsletter

Be the first to see our latest home tours, design news, and more.