The Placemakers

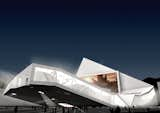

When you Google MVRDV, the first words to appear below the architecture office’s name are "Firm facts." Though signifying the company details listed on its website, the phrase could be MVRDV’s motto. Factual analysis is the avowed foundation of the office—–though this strict methodology belies the stylistic playfulness of their projects, from the Rubik’s Cube twists of the recently unveiled Gyre buildingin Tokyo to the sly, slinky humor of their "caterpillar" design for the future expansion and renovation of the Cleveland Institute of Art.

Winy Maas, one of the Rotterdam-based office’s three founders, along with Jacob van Rijs and Nathalie de Vries (the tongue-twisting name MVRDV is an acronym of their surnames), explains that the firm’s identity is founded on its approach. Maas characterizes it as "practical and dialectical," rather than aesthetic, which he derides as architectural "hairdressing." It’s a methodology that is best understood not from the varied manifestations of MVRDV’s architecture, butfrom its steady production of brick-thick polemical books, including Farmax, Metacity/Datatown, and KM3.

These tomes consistently argue for a new density in architecture, mining mountains of social and economic data—–from official statistics to interviews with local residents—–to create visual "datascapes" and propaganda-like arguments (many written by Maas, the vocal theoretician of the group) that tie the overarching manifestos to specific situations. As grounded in research as it is in architectural practice, MVRDV has even developed The Regionmaker, a set of software planning tools.

In its rigorous academic basis, MVRDV has much in common with Rem Koolhaas, whose Delirious New York launched a thousand urban theories; unsurprisingly, Maas and van Rijs worked with Koolhaas at OMA in the 1980s. Nathalie de Vries, meanwhile, was employed at Mecanoo, in Delft. The trio first joined forces to work on a submission for the Europan 2 competition in 1991. Their Berlin Voids entry formulates the kind of compact complexity that recurs throughout their work, but despite winning first prize, the design was never built. As a high-rise "it was the one thing you couldn’t do," de Vries recalls, given Berlin’s strict planning regulations.

Nevertheless, a booklet that the trio had made to accompany their entry caught the attention of their first major client, progressive Dutch TV broadcaster VPRO, which required a new head office in leafy Hilversum, the Netherlands’ media capital. The booklet was the first indication of the office’s talent for self-promotion; there’s a storythat, to land the contract, the architects"borrowed" an office and got friends to pose as their employees.

Later Maas announced, in a statement that became an MVRDV trademark, that the VPRO building would have the atmosphere of "a luxurious car parking garage" and no facade at all (heaters would instead mark the "climatic" boundaries of the building, and "air would become the main building material"). Building codes meant that it ended up with a transparent glass exterior, but it still meets Maas’s claim that it is "solely an interior…. In a building whose activity is mainly expressed by other media, any representation in the facade has been avoided."

From the first, MVRDV has claimed that its buildings do not result from any formal or aesthetic aim, but from the datascape of systems and relationships that proliferate in the modern urban landscape. Take the 13 small, cantilevered blocks parasitically dotting the side of their WoZoCo seniors’ apartment block—–they weren’t a stylistic choice, but the result of the project’s datascape, which showed that, allowing adequate daylight for each unit plus sufficient outside space, there was room only for 87, not the required 100. Thus, the remaining 13 apartments were, according to the architects, "reconfigured as ‘outboard units,’" and smacked on the exterior.

Nowhere is the building-as-data-scape as clearly worked out as in MVRDV’s Dutch Pavilion for Hanover, Germany’s Expo 2000. "We wanted to make an icon," says de Vries, and the stacked Dutch landscape turned out to be as much a symbol of the office’s own thinking as of the artificial, compactly populated nature of the Netherlands. The layer cake of tulip fields, dunes, and forests, topped by a lake and a wind turbine, is a working, self-sufficient example of natural density, with its own power and water systems. Using a tenth of the allocated plot, it creates, rather than uses, space.

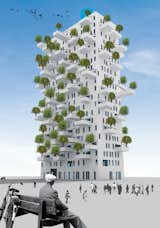

The enormous popular success of the pavilion reflects the MVRDV mission, according to Maas: "We want to position our work outside of architecture, as a clear piece of sociology and ecology," he says, "but to do that in such a way that not only architects understand it, but also the other 99 percent of the population understands it, and can debate it." The pavilion is a landscape equivalent of the "three-dimensional city planning" that MVRDV promotes as a response to urban expansion and population growth. The stackable city would halt the proliferation of sprawl, preserving what’s left of the world’s wild spaces.

The most infamous example of the firm’s high-density theorizing is its proposal for a high-rise pig farm, Pig City, based on the mind-boggling statistic that the Netherlands contains as many pigs as people (about 15 million of each). The Mirador housing development, built in 2004 in the Sanchinarro neighborhood of Madrid, is an example of how MVRDV turns existing typologies on their heads, in this case quite literally. The Mirador looks as if a quartet of low-lying blocks surrounding a courtyard had been upended and left standing like a monolith. The banal courtyard separating the blocks becomes a void, eloquently framing the distant Guadarrama Mountains.

MVRDV’s lively Silodam residential building in Amsterdam works a similar transformation by condensing what could be several neighborhoods within a single building. This collage of mini-neighborhoods, created for different functions and lifestyles, becomes what Maas calls "a mirror of the political and economic situation in Amsterdam." Its patchwork of interests indicates what client Suzanne Oxenaar (co-founder of the Lloyd Hotel) terms the office’s "natural attitude to be open to other disciplines."

Dutch architecture writer Bart Lootsma calls MVRDV "utopian," and Maas, even with his ironic (but never cynical) stance certainly seems to agree. "How architects form the new urban spaces will have an effect on a society’s culture for years to come, so design is a political issue for us," he says. Reason enough to try to make the world a denser place.

Published

Last Updated

Get the Dwell Newsletter

Be the first to see our latest home tours, design news, and more.