We Dream of Prefabs

Here are six examples:

First Penthouse

"Prefab" and "penthouse" are two words rarely put together—unless you're talking about the reading material of choice for a lonely guy living in a double-wide.

But with their company, First Penthouse, Swedish civil engineers Annika and Håkan Olsson have brought these seemingly disparate elements into blissful coexistence.

"The rooftops of the central London skyline are a resource that has been left uncultivated for far too long," reads the company brochure, "but one that is really only accessible if the heavy construction process is moved off-site." With property values soaring and urban density increasing, this is an idea whose time has come.

Founded in 1992, First Penthouse has developed projects in some of London's wealthiest neighborhoods and plans for New York and Paris are in the works. The husband-and-wife team negotiates a deal with a property owner to purchase a roof as if it were an empty lot and then designs an aerie per customer specifications. The luxury units are assembled as modules at a factory in Sweden—the process takes about ten weeks. After the units are outfitted and factory-tested, they are brought over from Sweden in shipping containers and lifted by crane to their top-floor destination. Once a module is positioned on the roof (which has been prepared for its arrival), it has a roof surface, working electricity, heating, and plumbing in about a day. The finishing touches on upscale, owner-specified amenities take about four weeks to complete.

Factory construction methods notwithstanding, these residences have price tags commensurate with their penthouse status—the Albert Court units sell for $4 million to $5 million—and the Olssons remain committed to serving this demographic. There are, unfortunately, no plans for a First Studio Apartment. —ALLISON ARIEFF

Pacific Yurts

Yurts. The very word makes people's eyes widen in curiosity. It suggests a deep mystery that only an exotic form of construction can generate. Simplicity, however, is actually the most intriguing component of this prefabricated housing form, which originated in Mongolia and Turkey.

In their Eastern homeland, yurts are prefabricated and also portable, allowing for a nomadic lifestyle. Constructed of simple wood poles and animal pelts, the tent-like yurts can be packed up and carted off in a matter of minutes. Nomadic life as it is known in Asia simply doesn't exist in the United States—unless you count Road Warriors or RV-ers—but that doesn't mean there is not a market, even a yearning, for yurts.

For the past 23 years, Pacific Yurts, of Cottage Grove, Oregon, has been dedicated to the production of the "modern" yurt. The main building block of a Pacific Yurt is a lattice wall, wrapped in an acrylic-coated, woven polyester. A ceiling structure of kiln-dried fir rafters fans out around the ceilings center ring, which doubles as a skylight. The roof is then covered with a vinyl-laminated fabric. After door and window installation, the yurt is complete. It takes just a couple of days to set up a 30-foot diameter Pacific Yurt (the largest size). All the materials fit in a pickup truck. And the basic yurt, which keeps you (somewhat) warm, (fairly) safe, and (adequately) comfortable, costs about $8,000 (excluding land cost).

The Pacific Yurt offers practical advantages, but really, who would live in one? A lot of people, from the Ozarks to the Caribbean, according to Alan Bair, president of Pacific Yurts. "Some sit in the backyards of mansions," adds Bair. Still, it is safe to say that the "yurt as home" concept seems to be best suited to the individual who, while not necessarily nomadic, dreams of a freedom from convention that only a yurt can provide. —ANDREW WAGNER

The Binishell

Asking an architect to design a building that could be raised within an hour would likely elicit a blank stare. But not from Dante N. Bini. For the last 40 years, the Italy-born and educated pioneer of "automated building construction sequences" has sought to defy our conceptions of the building process.

While not a prefab in the strictest sense of the word, Binishell, and its diminutive offspring, the Minishell, are a novel solution for mass production. More than 1,600 Binishells have been built and are used for a variety of functions, including shopping centers and gymnasiums.

While these sturdy structures may look like they require a serious amount of time and effort to construct, amazingly, most are raised in under an hour, with, as Bini proudly states, "less air pressure than it takes to puff a cigarette."

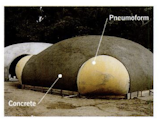

Here's how it's made: A pre-shaped "Pneumoform" (basically a sophisticated balloon) is rolled out and affixed to an anchoring system on a flat, octagonal base. PVC sheeting protects the surface of the Pneumoform so it can be re-used. The most time-consuming part of the operation follows—laying out an intricate, crosshatched system of stretched, steel-reinforced springs. Concrete is then poured, covered with an external membrane, and with the flip of a switch, inflation of the Pneumoform begins. In under an hour the Binishell (or Minishell) has taken its final shape. Air pressure and springs with steel reinforcement keep the concrete from sliding down the sides of the dome. For two days the concrete sets and dries, then the Pneumoform is deflated and fixtures are added to the openings.

Bini has since turned his attention to other projects, such as the Binishelter—low-cost, self-erecting housing for disaster relief. Reflecting on people's resistance to residential domes, and the dominance of right angles in home architecture, Bini says, "Only a few special people may choose a dome structure for living in." —SAM GRAWE

The Portable House

"What we're proposing is a rethinking of the trailer park and all the stereotypes that go along with it," explains architect Jennifer Siegal, principal and owner of the Office of Mobile Design in Los Angeles. "I like the idea of a contained, self-sufficient community, which a trailer park is. The ability to live and work in a compact environment is very appealing and allows you to create a sense of neighborhood—something you don't get in sprawling communities."

Siegal has focused on various aspects of mobile architecture throughout her career with projects like the Mobile EcoLab, an environmental workshop on wheels that travels to L.A. schools to teach students about environmental issues, and the iMobile, an online roving port for accessing global communications networks. Recently, OMD was commissioned to design a new mobile city for Pallotta TeamWorks, the creator of multiple-day fundraising events like Tanqueray's American AIDS Rides and Avon's Breast Cancer 3-Day Walk. The commission includes overall campsite master planning for Pallota's multiple-day events as well as mobile structures to accommodate the events' service, transport, housing, and vending needs. Siegal's Portable House is a natural extension of these projects.

Inspired by visionary housing schemes from Archigram to Arcosanti, Siegal sees endless possibilities in the Portable House. The 40-by-12-foot mobile structures are very compact and not exactly luxurious but they can, as Siegal explains, "exist in any situation. You're not bound or rooted to place. It's an idea that harks back to nomadism, and I see our generation responding quite well to that due to new technologies, the global economy, etc. I think this project is a response to the way we live and work today."

Siegal, who lives and works at the Brewery complex in downtown Los Angeles, hopes to buy some land in Venice, California, and produce a portable house for herself. Her ideal is to group three trailers together in a U-shape forming an inner courtyard: One you live in, one you work in, and one used as a communal space. But the configurations are endless: They can be stacked to expand vertically, for example, or attached to one another.

"I have a firm belief in doing what you spout forth, especially as an architect," Siegal says. "I want to prove that this scenario is a good one by living in it myself."—A.A

Acorn House Conversion Project

Since 1947, Acorn Structures (now part of Deck House, Inc.) has been producing "individually designed, pre-engineered houses," assembled on-site from factory-built panels. Where many prefab housing companies have failed, Acorn has succeeded—mostly because of the high degree of customization offered within the confines of "pre-engineered" design (six different Acorns can almost look like six entirely different houses.) Kennedy & Violich's (KVA) clients purchased two older, smallish, linked acorn houses atop a wooded hill on Cape Cod, with the intention of transforming the suburban structures into a "contemporary living and working environment," and the Acorn Conversion project was born.

Because KVA was asked to work within the existing footprint of the building, they developed an unusual solution to the client's desire for more space. They removed the low-slung ceilings, exposing the Acorn's prefabricated trusses and painting them white. In keeping with the Acorn vernacular, skylights were added above the revamped kitchen (set apart from the rest of the living space by a translucent glass wall that acts as both light source and diffuser). The newly reclaimed spaces were further transformed and obscured by hanging perforated aluminum panels, which, according to architect Sheila Kennedy, "under different lighting conditions appear alternately opaque, translucent, or transparent." Computer-aided manufacturing determined the exact amount of perforation needed to achieve the desired optical effect; as day becomes night, the panels dissolve, revealing the exposed trusses and hidden recesses of a "ceiling landscape."

In this renovation, KVA not only met their client's desire to reinterpret a conventional home, but with state-of-the-art manufacturing technology created, as Kennedy says, "a constantly changing perception of the volume."—S.G.

Dymaxion Bathroom

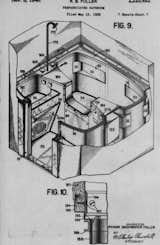

In the 1930s R. Buckminster Fuller invented the Dymaxion Bathroom, one of the first prefabricated bathroom units, and the first ever manufactured from die-stamped metal, like a car body. The interior—made from two sections of waterproof, water-tight sheet metal and two laminated plastic hoods—had a pre-plumbed sink and tub. There were no corners or crevices for mildew to fester. In less than an hour, two people could install it, even in a retrofitted house. The whole bathroom weighed—and cost—slightly less than a standard '30s bathtub. And in a spare, metallic way, it looked magnificent.

Fuller's ingenious design briefly charmed the Phelps-Dodge Research Laboratories, then got thwarted in a prototype stage by the unions of American plumbers who believed it would hurt their business. But Fuller's idea, enhanced by the advancement of plastic, has caught on outside the United States. In Japan, Sekisui House Ltd. builds adorable units that "adopt the principles of universal design." In England, European Ensuites Ltd. builds one-, two-, and three-function units, all made to order off the web.

U.S. manufacturers have all but forgotten Fuller's vision. Charles Robertson, founder of Restrooms.org has read bathroom feedback from thousands of Americans. "Everybody," he says, "wants to put their personality into their bathrooms. They want to hang pictures. And they're traditional about bathroom fixtures. They expect their bathrooms to be just like what they had as kids." As much as they rely on bathroom rituals, they relish the cumbersome construction ceremony: Lugging the tub, installing the pipes, grouting the grout, wallpapering the walls.

Robertson's wisdom explains why prefab bathrooms haven't caught on in America. But his reasons, like bathtub rings, are depressing. In the words of Alexander Kira, author of the famed ergonomic study The Bathroom: "American society at the moment is turning aside functional innovations for personalized extravagance."—Virginia Gardiner

Published

Get the Dwell Newsletter

Be the first to see our latest home tours, design news, and more.