Marcel Breuer Hooper House II

There’s a very fine reproduction of a Josef Albers "square" painting hanging in Dr. Richard North’s garage. Granted, it’s being kept company by a Bentley and a Ferrari, but the garage seems a rather undignified place for it. "Have you ever been married?" asks North, by way of explanation. His ex-wife, with whom he is still close, was not a fan of the work. So it ended up in the garage, where it remains.

North, a prominent neurosurgeon in Baltimore, has maintained much the same spirit of quiet accommodation with Hooper House II, the modernist gem by Marcel Breuer that he has owned since 1996. Although it was refurbished just before he bought it, the house has changed very little since it was built as an idyllic, near-the-city retreat. The 1959 house was Breuer’s second for the wealthy art-lover Edith Hooper and her husband, Arthur. Old and discolored acoustic tiling was taken down in favor of drywall on the ceiling; a messy oil spill in the basement was cleaned up; and some of the floor-to-ceiling sliding glass doors were replaced.

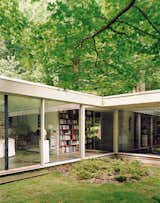

But mostly, it remains as it was: a long, low house of exquisitely laid fieldstone and expanses of glass.

It’s a textbook example of Breuer’s classic "bi-nuclear" house, a division of the home into spaces for adults and children. As you enter, through a ten-foot glass gap cut into the stony Zen blankness of the house’s 131-foot-long western wall, you confront an architectural Parents’ Bill of Rights: kids to the left (bedrooms, bath, and a playroom), adults to the right (living room, dining room, kitchen). "You want to live with the children, but you also want to be free from them, and they want to be free from you," wrote Breuer in 1955, a deliciously dated understanding of the familial balance of power.

The youngest of the three great Bauhaus practitioners to work in the United States (Gropius and Mies van der Rohe were the other two), Breuer was equally susceptible to his Bauhaus colleagues’ failings: the penchant for pronouncements and the dispiriting late-career work. And it will take, it seems, a few more revolutions of the cyclical wheel of taste before buildings such as Breuer’s brutal, expressionist offices for the Department of Housing and Urban Development in Washington, DC, are embraced by anyone beyond a coterie of die-hard devotees of mid-century concrete architecture.

But his houses, always admired and still remarkably livable, if North’s quiet engagement with the Hooper House is representative, are a different matter. In search of a property on which to build his family a new home, North studied maps of the area and discovered an extraordinary pocket of forest Mrs. Hooper had acquired decades ago. Before she died, he had tea with her twice in hopes of buying an empty parcel near her home. They sat in the glass-walled living room, dominated by one of Breuer’s trademark, no-two-alike fireplaces, with the forest on all sides. It became perfectly clear to North, on both occasions, that the very polite and rather austere Mrs. Hooper (who boiled water with an old-fashioned immersed electric coil) had no desire to sell anything at all.

And so, after she died, he bought the house from her heirs, an act in the spirit of Breuer’s pragmatic, if not exactly affectionate, accommodation of adults and children. North then replaced the roof and put glass doors on the fireplaces in the children’s playroom and the living room, considered taking down part of a wall to add a pass-through window to the skylighted kitchen (but later thought better of it), added garage doors to the carport, and converted the adjoining stables to make more garage space.

"I didn’t know any of the architectural history," says North. "But I suppose I had an eye for architecture." An eye inspired, he suggests, by his father’s career as an architect and his mother’s as an artist. His own career as a surgeon has also contributed to his minimally invasive approach to the house. When some of the bluestone flooring began moving underfoot, he talked to a contractor about having it relaid. Discouraged by that consultation, North set to solving the problem himself, using a tiny drill and a 60-cc syringe to inject an epoxy under the troublesome pieces. "In this otherwise very quiet setting, it was most disconcerting to have loose stones go bump in the night," he says.

If he didn’t know the house’s history, he does now. North has collected most of the available literature on the house in various languages. Although he originally prized the place as an escape, he is generous about letting the curious inside—the Hooper House has been written up in the local papers several times and extensively photographed. Clearly Edith Hooper’s vision retains the power to inspire: Shortly after it was built, Architectural Record praised its "forceful simplicity." Subsequently other writers have noted something "archaic" about it. And when Italian photographer Luisa Lambri shot it a few years ago, she said, "It was a very moody place, and it had a lonely feeling that was sort of sad."

These responses seem part of an ongoing misreading of the Hooper House, a view that casts it as an inert and ideal icon of its times rather than something organic and mutable. The "forcefulsimplicity" of it is all there in the plans. On paper, its rectangular form can be summarized with a few bold lines, a thick wall of stone on the west, a square courtyard with a rectangular opening cut in its eastern wall, and glass pretty much everywhere else. One expects a harsh study in contrasts, hard stone next to transparent glass, and perhaps the worst of both materials: cold solidity and naked transparency, a bunker with a view.

But sit in the Hooper House at sunset, and the clear, simple forms so obvious from the plans begin to blur. Shadows gather, the dining room merges with the greenery outside, and quiet envelops the house. The "archaic" stone walls soften, taking on new textures, and their very mass feels like an embrace. It isn’t so much a "moody place" as a place of many moods, each room different, connected to the whole as a chain of spaces rather than articulations of a grand idea. Breuer once quoted Lao-Tzu’s Tao Te Ching to describe his understanding of architecture: "Though doors and windows may be cut to make a house, the essence of the house is the emptiness within it." Lambri was half right: It is a study in a kind of emptiness, but hardly a sort of sad one.

As organizations such as the National Trust for Historic Preservation champion the cause of mid-century-modern houses—searching for wealthy buyers who won’t raze or expand them beyond recognition—North’s marriage to Hooper House is a happy accident. It was a place, green and apart, that he was seeking when he discovered it. Every Breuer house is a response to a site, a union of the man-made and the natural. The Hooper House, with its fieldstone walls and forest setting, feels as if it were charmed out of the landscape, and it has in turn charmed its owner. A real estate agent might ask why the bedrooms are so small, why there are no windows in the playroom, why the bathroom is so very out of date. To which the current owner might reply, philosophically, "Have you ever been married?"

Hooper House II's new owner, Richard North, has altered the house very little, though he did convert the carport into an enclosed garage to provide greater protection for his collection of automobiles.

A large rectangular cut in the back wall of the house creates views from the entrance through a courtyard to the trees and lake beyond.

North stands outside his glass-walled living room, which also houses his small library of books about Breuer.

The courtyard captures nature within the embrace of the house, a "room" of green that is simultaneously indoors and outdoors.

Although the house was refurbished before North bought it in 1996, it still includes some of Breuer's original built-in furniture, including the desk in the bedroom, as well as a chair designed by the architect.

The playroom, lit by skylights, is now a reading and television space for North, whose children are now adults.

Three stark planes make the dining room a place of sun and shadow: a wall of rock, a floor of bluestone, and a sheer slice of glass. Further adding to the unity of the house, the tubular steel dining chairs were also designed by Breuer.

Published

Last Updated

Get the Dwell Newsletter

Be the first to see our latest home tours, design news, and more.