How Will Architecture Merge the Digital and Physical Worlds?

"Who remembers places?" reads the white text of a meme that went viral in March, not long after pandemic lockdown measures paralyzed the U.S. Accompanied by a picture of a generic strip mall, the image struck a universal nerve. Locked inside of our houses, the idea of visiting offices, bars, shops, and restaurants conjured a strange nostalgia.

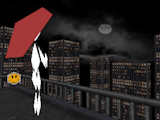

Less than a month later, that text inspired the title of an experimental video game. "Remember Places?" was created in a five day, online game development competition, where the first requirement was to "make a game to fill this cold empty void." At one point in its storyline, the player walks on a rooftop in a dark, blocky city, guided by a humanoid figure named AI. "You used to gather in large columns like these," it says, gesturing towards the office towers nearby. "I hope you are feeling wonderfully nostalgic, like you are really here."

If this feels unsettling, that’s because it is—"Remember Places?" demonstrates that we’ve lost not only the old staples of normalcy due to the pandemic, but increasingly we are losing our tight control over our perceptions and experiences of the real world to an inorganic intelligence. How this "meeting of the minds" will play out in public spaces is of particular concern. According to architects and programmers, our anxieties are not unjustified.

"Today, people are used to interacting in massive, public forums in digital space. These types of interactions often feel very impersonal but communication can be expansive," says Noah Waxman, head of strategy at Cactus, a firm working at the crossroads of architecture and software. "On the other hand, people are also used to going out in public spaces where they can see, and be seen by, many other people at once. These types of interactions often feel personal but communication is limited."

According to Waxman, these two worlds of digital and physical public space will soon converge. "The proliferation of 5G connectivity, surveillance technologies, and AI-enabled computer vision will enable people to be in conversation with others that share physical spaces in new and interesting digital ways," he says. "Imagine everything from augmented public art projects to interactive public theater productions to massive collaborative graffiti projects."

Cactus has first-hand experience in ushering in this new type of world. Capitalizing on the (pre-pandemic) experience economy, the company designed and built The Color Factory, an experiential pop-up exhibit that made appearances in San Francisco, Houston, and New York City in 2017 and 2018. The exhibit implemented MIRA, an automated photography system designed by Cactus, to take Instagram-worthy pictures of visitors as they frolicked and posed throughout 16 rooms of visually stimulating playgrounds and installations. MIRA promised guests an opportunity to enjoy the moment, secure in knowing that "they are getting amazing documentation of their experience without having to do it themselves." According to the product's spec sheet, the system could also be implemented to use fingerprint and face scans to "authenticate" guests.

If it seems that places have ceased existing as they were, it's because they have. We come to them through digital maps, we find them through search engines, we revisit them on social media. But in the near future—sooner than we may be ready for it—the places themselves will photograph and document us. Built into the fabric of our cities, AI could turn our urban settings into another social media platform, where user-data is collected, processed, and used to update the real-world environment towards more "engagement," "impressions," and "conversions."

This vision is not new. The idea of autonomous, digitally-powered, intelligent buildings and public spaces has been a long time in the making. In 1976, Cedric Price, a professor at the department of architecture at Cambridge University, unveiled a radical proposal called GENERATOR, which hypothesized a model for a non-prescriptive architecture, where buildings would not define uses, but instead, adapt in a hyper-flexible and intelligent way to changes in inhabitants' needs. GENERATOR's movable building modules, implanted with computer chips, could work to house dancers, actors, and visiting artists, and would suggest new configurations of space depending on their behavior. At the time, the full potential of Price's model could not be realized because of the limits of computer science.

Stanislas Chaillou, an architect and engineer at Spacemaker AI, an architecture-oriented software engineering firm, thinks the ideas underpinning GENERATOR are now an undisputed reality.

"For the past 15 years, we've been very much into this descriptive path. We've been using heuristics and simple sets of mathematical rules to encode instructions and tell the machine how architecture happens, and what rules it should follow in order to draw a building," Chaillou tells me over a Zoom call. "Machine learning and AI flips this logic and says: No, we're going to substitute observation for description; we're going to relentlessly show millions of examples to machines so that they learn how to execute designs themselves. We've moved from describing what the machine should do to allowing it to observe and learn."

AI isn’t the be all and end all pathway to architecture’s melding with the digital world, though. Joshua Pearce, a 3D printing pioneer and academic engineer at Michigan Technological University, predicts that the most impactful digital effects on the built environment could emerge by developing an open-source software culture in architecture and construction.

"Today, public domain and open source software dominates in the programming field," says Pearce. "I can confidently predict that within the next ten years, we will see many more public domain and open source physical objects, ranging from consumer goods to large scale buildings."

Pearce attributes much of the success of tech giants, such as Google, Facebook, and Amazon, to the abundance of open-source technologies available to programmers, thanks to a culture that prizes the free flow of information ahead of intellectual property or professional gatekeeping. Pearce is a board member of the Open Building Institute, a platform that collects open source plans for low-cost housing and aquaponics greenhouses. He hopes the library of designs it contains will grow in the future, and that people will one day be able to collaboratively work and expand upon architectural designs in the same way they develop code.

"Public domain designs will proliferate and be digitally manufactured by a growing cadre of large-scale 3D printers and other digital manufacturing technologies," he says. "We should see the costs of buildings drop even as they become more customized and aesthetically pleasing."

"Infrastructure Prosthetics" a student project from SCI-Arc professor Mimi Zeiger's class, envisions an affordable housing complex that densifies over time using procedurally generated forms that meet complex site requirements.

Academia is already starting to test Pearce’s predictions. Last spring at the Southern California Institute of Architecture (SCI-Arc), architecture critic Mimi Zeiger and algorithmic design expert Casey Rehm co-taught a course, "AI and the Future of Housing", that encouraged students to fuse digital resources—open source data, AI, and 3D printing—in order to find solutions for the housing shortage in Los Angeles.

"We were exploring the relationship between housing and AI," says Zeiger, "by using neural networks and machine learning software to look at L.A. County data, and create predictive softwares that might help identify sites that were previously not available for use for ADUs."

Knowing where ADUs could be built according to recently changed regulations in California could encourage the construction of more housing and help with the densification of suburbs. In their projects, the students used open source data and AI models to assess the economic and zoning feasibility of sites, and 3D printing to overcome site limitations—such as steep lots—to propose efficient ways to deploy ADUs across Los Angeles County.

The students' work presented a bright vision for what AI and digital tools could accomplish in the near future. But when I asked Zeiger whether she was concerned about whether these same digital technologies could invade our public spaces, negatively influencing the creative process of architects, she brought me down to level-ground.

"I think larger threats on civic space are unmarked federal officers or commercial interests taking over," she said. A little while later, she quoted Neuromancer author William Gibson: "The future is here but it's not evenly distributed."

Published

Topics

Where We Live NowGet the Dwell Newsletter

Be the first to see our latest home tours, design news, and more.