Baton Rouge Oasis

In the early 1960s, the planning misstep known as urban renewal swept across the United States. As in many other places, downtown Baton Rouge, Louisiana, was harshly reconfigured, while new interstate highways fractured thriving working-class and ethnic neighborhoods. Forty years later, on a small, oddly shaped site literally steps from the pylons and semitrailer traffic of Interstate 10, architect and Louisiana State professor David Baird and his family have carved out a surprisingly placid, versatile life in a house that connects them with their diverse, resilient neighborhood.

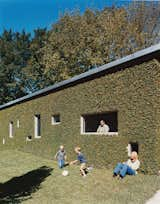

"Most homes take the idea of the fortress to protect the inhabitants from the uncertainties of the outside world," explains the Nebraska-born, Iowa-raised architect from his cheerful and bucolic living room, while just steps away 150,000 cars per day zoom past at 70 mph. "But what we really wanted to do was create a building that would engage the neighborhood and the community." Baird met those goals by bringing nature, and his neighbors, into the living space while simultaneously protecting the house, its inhabitants, and the rest of the neighborhood from the sensory pollution of the interstate. The 2,000-square-foot, bar-shaped structure is oriented to block the view and noise of the highway from the street, creating an island of calm where, one suspects, it did not exist before.

Built on a lot that didn’t even appear on the city’s zoning maps, the house exploits the site’s corner location and narrow shape to the fullest extent. "We knew this was the area that we wanted to live in," says Baird, citing proximity to one of Baton Rouge’s only mixed-use commercial centers, where locally owned restaurants and nightspots coexist with bookstores, boutiques, antique shops, and the venerable Perkins Road Hardware.

Baird adds, "I was confident that we could make the appropriate choices, reclaim this piece of land, and live here with dignity."

After a nine-month title search owing to the complexities of Louisiana’s Napoleonic law, David Baird, his wife, Sarah, and his son Bo (now joined by younger brother Sky) created a home on the once-garbage-strewn but very affordable corner site. "We really lucked out on the lot. I think that most people just passed by it and didn’t see the potential in it," Baird notes. "You couldn’t have put a standard house here and done well with it, because it was a little bit of an unusual site, backing up to the interstate and on the hinge between a commercial area and a residential area. That’s one of the benefits I see in modern architecture, its ability to adapt to certain site conditions in an elegant way."

A screen of ivy softens the hard edges of the cinderblock structure, as do the exterior’s three large, spotlit billboards. Baird, who wrote his graduate thesis about billboards, designed custom frames to display vinyl banners that can be printed with any image at a cost of about $700 for the three. Echoing the vernacular landscape of the neighboring interstate, the concept also has a more humanistic goal, engaging both private and public space. "I think of the billboards like clothing for the house," Baird says with a laugh. "And you can change the outfits without having to repaint the entire structure or go through some huge expense."

With construction costs of only $55 per square foot, the house is also a study in frugality (not to mention versatility and appropriateness). Exterior landscaping is dramatic yet welcoming, ushering visitors into a comforting, semiprivate entry space before they even enter the house. Despite the iconic nature of the southern front porch, hot Baton Rouge summers and proximity to the interstate made that feature impractical. Instead, large, uncurtained glass expanses in the front rooms create a porchlike feel, with tree-filtered light flooding in during the day. The inoperable but energy-efficient commercial-style windows and concrete shell also block out ambient highway noise and moderate the heating and cooling loads.

The open, modular floor plan balanced cost and utility, minimized construction, and reduced the number of doors and accompanying hardware. Baird says the house is devoid of "heroic" materials, explaining, "We didn’t want to spend a ton of money on the kitchen and the bathrooms, and I think that’s where most expenses occur in a home. Instead, we made a conscious choice to make those moves very modest in favor of creating fewer, larger rooms." Classic, workmanlike design with a few well-chosen flourishes creates a space that is at once dramatic, livable, and affordable. Off-the-shelf fixtures are balanced by creative, eye-catching solutions, such as a kitchen island built from mechanics’ tool chests and a plywood top.

Given the site’s proximity to a growing commercial district, overall flexibility was another goal. The spaces are designed to be quickly and cheaply adapted should economics or future development make it desirable to convert the house to commercial use. Built-in closets, for instance, are eschewed in favor of freestanding metal cabinets that, like most of the furniture in the house, are on casters.

In fact, the house already performs many of those dual roles. The original master bedroom in the rear of the house is currently home to PLUSone Design + Construction, the burgeoning practice Baird operates with partner Fritz Embaugh and staff designer Greg Gauthreaux. As if that weren’t enough multitasking, Baird is also a prolific sculptor and painter, and the family is an integral part of the Baton Rouge art scene, regularly hosting openings and performances in their multipurpose home. "We really wanted a house that would facilitate and encourage an appetite for art in the community," Baird notes, boasting that the house offers more track-lit wall space than any commercial

gallery in Baton Rouge.

The synergy of form and function also facilitates Baird’s vision of the higher purposes that architecture can perform, creating an open and welcoming community space. Local residents regularly wander in during the family’s art events, and some have walked out with a purchase made directly from the artist. Baird finds this immensely gratifying and is happy to help foster the local arts and culture scene, which comes out in droves to the events held at his house.

An unabashed booster of his adopted hometown, Baird often recalls the unbridled populism of another of the city’s great promoters, former Louisiana governor and Baton Rouge scion Huey Long. Instead of politics, Baird works in subtler ways, starting with this modest, infinitely adaptable cinderblock building next to a highway underpass. Inhabiting the many roles of architect, teacher, artist, and parent with equal passion and conviction, Baird’s life seems as holistic as his designs. "I think in our contemporary society we tend to chop things up into little boxes and try to categorize parts of our life, and when we do that we cut opportunities to create synergy between those things," he says with just a hint of disdain in his voice. "I know that for me personally, all those things feed off and inspire one another."

Join Dwell+ to Continue

Subscribe to Dwell+ to get everything you already love about Dwell, plus exclusive home tours, video features, how-to guides, access to the Dwell archive, and more. You can cancel at any time.

Already a Dwell+ subscriber? Sign In

Published

Last Updated