Ask an Expert: What Is Biophilia, Really?

In our Ask an Expert conversation series, we get design advice from leaders in the field. If you have questions for our experts, leave them in the comments, and we'll follow up. This edition is supported by Deltec Homes, but the Dwell editorial team is responsible for its content.

"We joke sometimes that we’re giving you the science behind the intuitively obvious," says Bill Browning, who with architects Rick Cook and Bob Fox started the research and consulting group Terrapin Bright Green in 2006. Terrapin is best known for championing the idea of biophilic design, which considers how humans innately respond to forms found in nature—and how we can incorporate those forms into architecture to create healthier environments. They offer a framework for considering how, say, a well-placed window and particular patterns in fabrics and building materials can positively affect the wellness of people who occupy a space.

"Biophilic characteristics of furniture include nature‒inspired materiality and haptic experience, organic form, implied cultural ties through craftsmanship or patterning, graceful aging and patina, or a meaningful contribution to the spatial experience," write Ryan and Browning in Nature Inside: A Biophilic Design Guide.

The organization works with designers, companies, academic institutions, cities, and other clients to introduce biophilia research into the design and planning processes. Catherine Ryan joined Terrapin 12 years ago, bringing a background in sustainable infrastructure, and has since consulted on projects ranging from a study of energy from algal biofuels to master plans for entire neighborhoods. Some of Terrapin’s recent work also includes consulting for the ecologically branded 1 Hotels, and health, well-being, and sustainability consulting for Portland’s PDX airport terminal core redevelopment.

Browning and Ryan have a primer on biophilia coming out this September. The book, titled Nature Inside: A Biophilic Design Guide and published by the Royal Institute of British Architects, is geared toward designers and covers everything from building better hospitals to the benefits of pocket parks and promenades in cities. One chapter covers home design, so we asked them how to incorporate the benefits of biophilia into our homes. But first...

What, really, is biophilic design?

Browning: In its absolute simplest terms, biophilic design is design that intentionally connects people to experiences of nature. Seeing living nature actually helps with cognitive performance, stress reduction, and mood. Even looking at an image of nature for 40 seconds will switch the way your brain processes information to a mode called attention restoration. The prefrontal cortex quiets down as you expend less energy, and after you’ve had that view, you’ll be less stressed and you’ll have better cognitive capacity.

How does that translate into interior design?

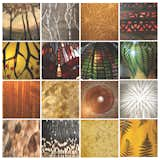

Browning: When you see the forms and fractal patterns that appear again and again in nature in human-designed objects, it’s much easier for the brain to process them. The term sometimes used among the neuroscientists is fractal fluency. We are already fluent with those forms from nature, so when we see them we like them—but more importantly, our stress level drops measurably.

"Biophilic textiles can introduce or complement visual complexity, depth and tactile variability to a materials palette and present an opportunity to explore illustrative and abstracted representations of nature," write Ryan and Browning in Nature Inside: A Biophilic Design Guide.

What does that mean for how you advise designers and clients?

Browning: We have a language of 15 different patterns found in nature. Some are really helpful for stress reduction, while others are great for cognitive performance, and some help with mood and emotion. You can look through and see which of the patterns support which of the outcomes, and then choose which one is the most appropriate for a space. For instance: While queuing for a security gate at an airport, stress reduction is pretty important, right?

What about for our homes, now that many of us have been stuck there for extended stretches?

Ryan: You see all these news articles coming out about people getting plants for their homes or wanting to go to the park, which reinforces everything we’ve been talking about.

Browning: Nature deficit disorder. It’s a real thing.

Here’s the question: Is the recognition that we need a better connection with nature going to stick? Or are people going to go back to their normal practices and forget about that whole "amazing connection with nature" thing?

"Paints and varnishes, floor and ceiling tiles, wall coverings and flooring offer multiple opportunities for biophilic content. Patterning, implied textures and representations of nature are good visual strategies, while dimensional textures, materiality and differing thermal conductance add to a multisensory experience. Examples of biophilic finishes include wood, cork, bamboo, coarse or veined stone; washes or stains that retain evidence of wood grain; and ceramic, clay or glass tiles that play with light, color or texture," write Ryan and Browning in Nature Inside: A Biophilic Design Guide.

What design advice do you have?

Browning: If you’re stuck in the house balancing work and family, refuge spaces are especially important: window seats, the inglenook by the fireplace, breakfast nooks. These spaces should be much more a part of the conversation. You don’t need refuge all day long, but you need it periodically.

And what about plants?

Browning: Obviously, plants have become really popular. One of the things we point out is that a plant is nice, but what’s nicer is creating a little ecosystem or habitat—a miniature landscape to project yourself into. That experience is one reason why terrariums are more fascinating than plants just sitting on a desk. The theory is that the brain goes, "Oh, look, there’s a little habitat—this must be a good place for me to be."

It’s like a little tree in a pot versus a bonsai landscape. The landscape is much more intriguing and interesting.

"Scalloped sinks, claw‒footed baths and ornate pendant lights are quintessential biophilic fixtures...Tiffany lamps are an enduring example. Off‒the‒ shelf lampshades with biophilic characteristics are low‒hanging fruit for incorporating a nature connection," write Ryan and Browning in Nature Inside: A Biophilic Design Guide.

Are there things that you often see neglected in home design?

Ryan: Even if you have a minimalist aesthetic where everything is white and beige, or light gray, you can still incorporate pattern or texture—and it will be beneficial. Think of biophilic design as a filter when choosing upholstery or textiles. If you’re set on beige, does it have to be plain beige—or can it have a little texture or color variation? What are the other options out there? If you have three choices, and you like them all, which one’s more biophilic?

Browning: Look at the wood grain. Look at the structure of the fabric. But it’s not just about finishes. Biophilia is a wholistic approach that can extend from the architecture of the building to the interior and the lighting. If they’re all tied together into a cohesive design concept, then if you end up wanting a plain carpet, you’re not stripping out the experience. It’s just expressed in different ways.

Ask an Expert: Have a question for Bill Browning and Catherine Ryan? Ask it in the comments.

Published

Last Updated

Topics

How-To & GuidesGet the Dwell Newsletter

Be the first to see our latest home tours, design news, and more.