A Party House in Hacienda Agua Caliente

In the living room, mid-century classics are the foundation while art from the house’s "coming out" party by Enrique Ciapara adds some personality.

The house itself—jutting out of a ragged hillside adjacent to a nearly vacant lot occupied by a lonely and forgotten billboard—reflects the budding pride of a community that for years has called this metropolis of around 2 million home. It’s also a reaction to the chaotic nature of the city’s largely unplanned growth, which has rapidly crept up over the surrounding brown hills.

The festivities were an invitation to the entire town to take part in a sort of mini-revolution in art and arch-itecture in a city not normally associated with either: a revolution whose main purpose was to challenge conventional thinking about the architecture of Tijuana and to shine a light on the complicated existence and dual identities of those who reside on the border.

That house is now home to architect Jorge Gracia and his wife Paola, their young son Maximiliano, and the family’s two German schnauzers, Rusky and Kata. It’s not surprising that Jorge, with his thick black hair, gracious smile, and proactive stance on the built environment, helped bring together this growing group of artists and architects, except that in Tijuana such undertakings are more often talked about than realized.

Tijuana was founded in 1889 and blossomed in the 1920s and ’30s as a gambling haven for Hollywood stars whose wild side was curtailed by prohibition in the States. But in the late ’30s, in an attempt to make Tijuana a respectable place rather than one of ill repute, the Mexican government outlawed casinos, and things took a turn for the worse. During World War II, however, the economy picked up as Tijuana established itself as the center of manufacturing that it remains today. Its proximity to California, and its abundance of cheap labor, have since kept Tijuana growing at a remarkable pace. As architect René Peralta explained in an interview with the Architectural League, Tijuana "has been created in spurts, it reacts to purely economic issues."

While it’s hard to argue against the economic growth of recent years, the arts and architectural community—among others—has not been well served by it. In place

of well-considered expansion, the city has experienced a whirlwind of inadequate, often very unsightly govern-ment-funded social housing controlled by large-scale developers. In a town with few examples of good design, finding clients willing to take even the most mundane architectural risk is next to impossible. "I’m an architect in a city with no architecture," Jorge explains, echoing the sentiment of so many architects in Tijuana. "In a place like this, you have to ask a client to have faith, and faith to me has always been the belief in something you can’t see."

But with faith on the wane, many of the young architects in the city have been forced to do work for themselves, taking advantage of one of the exciting things Tijuana does offer: little restriction as to what you can build. In 2003, inspired by San Diego friends Jonathan Segal (seen in Dwell, September 2005) and Sebastian Mariscal (Dwell, March 2004), and a host of other local architectural stars, Jorge decided to dedicate his time to his hometown. So with the help of his and Paola’s families, they found a lot that they could afford and quickly purchased it. "We loved the views," Jorge says. "That’s what attracted us."

Tijuana is a rambunctiously hilly city, and the Hacienda Agua Caliente neighborhood occupies prime real estate for taking advantage of sweeping views. The houses surrounding the Gracias’ are like many of the new structures sprouting up throughout the city—Spanish-style revivals with heavy tile roofs, stuccoed and painted in the pale hues that have come to signify what the locals call "California-style houses."

But Jorge, of course, had a different plan for his home, one that would encompass what he calls "the unexpected things that can happen everyday in Tijuana, from culture, to politics, to design." "With the house," he continues, "I wanted to make a statement and turn the engine of this unexplored, creative city. A city of trans-ition; an uncontrolled growing city where a new culture is emerging from the mixture of two."

To capture a little bit of this unique mixture, Jorge conceived of his home as two separate but compatible structures, one clad in redwood siding, the other in translucent white carbonate panels that glow subtly in the night. The two volumes are intricately bound together by a galvanized metal–skin stairwell with four glass bridges.

Entering the house from the aluminum bridge leading from the street to the front door, you encounter the double-height ceilings of the sitting room on the first floor. Floor-to-ceiling glass offers up expansive views of the city just beyond the concrete foundation that keeps the house from tumbling down the hillside. Cinder-block walls fence in the slightly askew grass-and-gravel backyard that is home to dogs Rusky and Kata, and also make for a great space for murals. Jorge explains that he wanted to frame the views of the city as much as possible and let the house engage itself, as well as its surroundings. "A kind of self-examination," he explains.

To this effect, each structure has windows on all sides—to the south, the city; to the north, the immediate neighborhood; and to the east and west, the Gracias’ home itself. Long and lean decks punch their way from the front and back of the house. Walking through the home, you are constantly reminded of the push and pull of Tijuana’s unique place in the world.

Paola and Jorge’s bedroom occupies the second story of the redwood structure while Max’s room settles neatly into the panel-clad unit. To gain extra space for an office and maid’s quarters, Jorge excavated the land rather than build a third story. The downstairs now provides living space for their live-in maid and, just recently, a particularly spectacular, if not especially large, office for Jorge’s growing practice. "Since my son was born, that really finalized my decision," Jorge says. "Not only did I want to commit myself to Tijuana but to my house and family." So, across the gravel courtyard from the maid’s quarters, Gracia put up four plates of glass around the steel girders that support the vinyl-clad structure, a surprisingly simple but striking solution.

With the office open to the backyard, Rusky and Kata tussle with one another while keeping a watchful eye on Jorge as he lays out plans for his upcoming projects—projects that have become much more frequent since his coming-out party for Tijuana’s arts scene just over a year ago. Sliding open the glass doors, Jorge basks in the city around him and wonders what the future holds for his hometown. As Paola and Max prepare a meal just upstairs, one thing’s for sure: A traditional lunch is not far away. And with another energetic young architect staying put in Tijuana, the dream of the city as more than just a hodgepodge of tattered buildings strung together along makeshift streets is a little closer to reality.

Paola Gracia keeps an eye on Kata, one of the couple’s schnauzers, from the second- story balcony. In the shade below the balcony is the dogs’ house, meant to mimic the Gracias’, that architect Jorge Gracia built from leftover building materials.

The two structures that comprise the house frame views of the ever expanding city. The backyard is perfect for frolicking dogs and children, with concrete block walls just high enough to keep them in but low enough to not keep the city out.

Jorge appreciates his efforts at twilight. The polycarbonate panels that partially clad the exterior of the structure provide a warm glow, adding life to Tijuana’s densely packed rolling hillsides

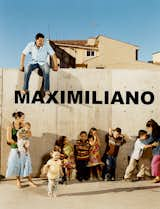

Jorge and Paola proudly displayed their son’s name on their back patio for his christening. With plenty of cousins to keep him company, Max (in Paola’s arms at left) will undoubtedly be pleased that his parents decided to stay put in Tijuana.

Jorge finds some time to relax in the living room. Chaise longue by Le Corbusier; coffee table by Noguchi.

In the kitchen, Jorge worked with local cabinet makers, Muebles Finos JV, to create ample storage, leaving countertops uncluttered. The LEM Piston Stools are by Shin and Tomoko Azumi.

Published

Last Updated

Get the Pro Newsletter

What’s new in the design world? Stay up to date with our essential dispatches for design professionals.