10 Minutes with Marc Newson

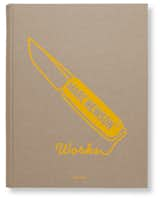

Your work has been published in several books; why was it time now for a complete catalogue, and why Taschen?

It was time six or seven years ago when we started, but it took that long to get it done. And why Taschen—well, I met Benedikt about six years ago, and we just got on so well. It became immediately clear that I could really only do this with him. I’ve done a book before, but not even remotely on that scale, so I had a little bit of experience—just enough to know that I needed someone who was going to let me do what I needed to do, which was something really significant. Not just a selection of things; I wanted absolutely every single little thing.

Is there anything you wanted or had to leave out, or is all your work in there?

There are one or two or three things I can’t remember that I think I maybe forgot. There’s just so much stuff. There are a couple of projects I did when I was in art school maybe, one or two, but I’d say 98 percent of everything is in there. I intentionally wanted it that way. There are some things that I’m not really that proud of, in the section of unrealized projects. It’s kind of the good, the bad, and the ugly, you know? But that’s important for people. Anyone who’s going to be interested enough to read about me in a book, or buy it, is going to want to have as much information as they possibly can.

We’ve noticed some variations on a theme in your work, such as the back of the Riva boat; the way it curls around is reminiscent of the Felt chair, the Wicker chair, the Orgone lounge—all similarly left open. Is this by design? Do you intentionally play on similar shapes across different design platforms?

It’s not something that I do necessarily intentionally. There are design cues; there’s kind of a DNA that runs through themes that I sort of pick up on. And it’s not really conscious, but at the same time there are shapes and forms that I feel comfortable with and feel familiar with, so they keep cropping up. You know: holes. Looking inside. The back of the Riva is like the beginning of a hole. It’s just something that’s sort of familiar to me that’s become recognizable.

It’s definitely somewhat of a signature of yours.

It’s an evolution; I don’t have a catalogue of things I pick up on. Some things I discard; other things I reinvent.

You’ve designed across many genres and over different affordability scales. Take the Nimrod chair; it’s more of an affordable item, and then there’s the Lockheed Lounge, that sort of ran away, probably more than you ever would have expected as the designer…

More than anyone expected; it holds all the auction records as the most expensive piece of work by a living designer. The last one sold for $3 million!

So on the other end of the spectrum, how important is it for you to have a good range of affordability in your products?

I think that sort of variety is healthy. Certainly for me it is. I don’t want to just get typecast as being a designer who only makes expensive things. For a start, I never intended for that to become so expensive, necessarily; it kind of happened without me. The nature of design is that I need to be able to do all of these different things. It’s kind of a problem-solving exercise. As a designer I think you’re compelled to be interested in just about everything. And if you’re not, then you’re probably not a very good designer.

We wanted to ask you about the problem-solving aspect of design. Charles Eames used to talk about solving problems with design.

That’s interesting, because I talk about it all the time. I’m in good company, then. I’m a gun for hire, and a troubleshooter. That’s what I do; I solve problems for people. Because they wouldn’t come to me if everything was O.K. There’s a reason—there’s something that they can’t figure out. And almost all of the companies I work with have in-house design capability; they could do it by themselves if they wanted. For some reason, they choose not to.

One of your most unique designs is the nickel surfboard. Did you design it specifically for [the big-wave surfer] Garrett McNamara?

At the very beginning, I wasn’t sure who was going to ride it, but Garrett immediately put his hand up and said, "I’ll do it." We’re getting him another one now. He just surfed the biggest wave in the world, in Portugal. They just discovered this new, 100-foot wave. He’s going back there at the end of the year to ride it. And he needs this board to do it. It’s really only good in extreme surf, because it’s heavy and completely rigid, which is why it’s so good for that kind of stuff.

You’ve talked about being fascinated by the concept of flying, and have designed many amazing flying machines. We all fly in our dreams, I think. How do you fly?

It’s true, I do fly. I haven’t done it for awhile, but I kind of float with my arms like that [places his arms at 45-degree angles] and lean forward. I think most people must fly like that, no? Looking down? I always kind of end abruptly, though, which is slightly disturbing [laughs].

What are you working on now?

I’ve got a ton of projects going on, all sorts of things. The most exciting project I’m working on right now is with Knoll. I’m doing a really fantastic big project with them—office chairs, and a number of other things—a serious industrial project. It probably won’t hit the market until 2014.

Published

Last Updated

Get the Dwell Newsletter

Be the first to see our latest home tours, design news, and more.